New research from Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO) suggests that when separated parents in England and Wales use the family court to reach decisions about a child’s upbringing, almost half of the children involved are not formally asked how they feel about the arrangements being made, even though they are likely to have a significant and long-lasting impact on their lives. A striking finding is that a child’s age has little effect on whether they have an opportunity to participate in proceedings.

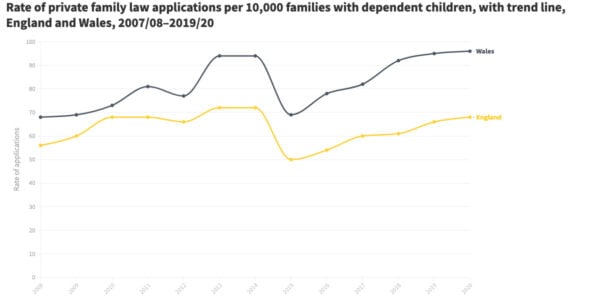

The study, carried out by the Family Justice Data Partnership – a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University – explored children’s participation in section 8 applications (for child arrangements, specific issue and prohibited steps orders) that started in 2019 in England and Wales. It suggests that of the 67,000 children involved, around half did not have an opportunity to formally voice their wishes and feelings or be involved in decisions that could potentially be life changing. The research mirrors findings from an earlier Nuffield FJO and Family Justice Data Partnership study, but also reveals that even older children and teenagers are often not involved in decisions. For two-fifths of children aged 10 to 13 in England, and a greater proportion of older teenagers, there was no indication that they had formally participated in proceedings, with a similar pattern seen in Wales.

A child’s right to participate in decisions being made about them and the importance of considering their wishes and feelings when making decisions is acknowledged in legislation and guidance, including section 1 of the Children Act 1989, Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Research has also highlighted how important it is for children to feel heard and understood when the family court is making decisions about them, and the distress they can experience if this does not happen. Giving children a voice in matters that concern their welfare has also been found to improve their experience of proceedings and the likelihood that they feel positive about the decisions that the court has made.

There is currently no universal process in England or Wales to ensure that children’s voices are systematically heard in private family law cases, and the family court will often make decisions about a child’s life without hearing from them directly. Within the current system, a child can only formally participate through welfare reports or, in a small minority of cases, the appointment of a guardian. However, these measures are not ordered in all cases, and under the current framework cannot be ordered before a first hearing. Furthermore, they do not necessarily mean a child has been consulted; a report may be written, or the child might be observed, but this does not mean their wishes and feelings have been obtained.

Commenting on the research findings, Olivia, a 21-year-old member of the Family Justice Young People’s Board, said: “It is simply not good enough that only half of children and young people get to participate in decisions being made about their future. These decisions can easily affect the course of their life and the fact they do not get a say is appalling. The report raises important questions about how, in cases where the child has no participation, the court was able to consider the child’s wishes and feelings, as the law says it should.”

The research findings and the concerns they raise help strengthen the case for the expansion of the private law Pathfinder court model, which includes engagement with all children as standard. Funded by the Ministry of Justice, it was launched in North Wales and Dorset in early 2022 and is soon to be introduced in Birmingham and Cardiff and the surrounding area. The court takes a problem-solving approach towards disputes between parents over arrangements for their children. There is an explicit focus on enhancing the voice of the child by giving all children (not just those with identified welfare concerns) an opportunity for their wishes and feelings to be heard before the first hearing, through the preparation of a Child Impact Report.

Lisa Harker, director of Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, said:

“Hugely important decisions are made about a child’s life during private law proceedings – but a strikingly large proportion of children aren’t seen by the professionals involved, and have no voice. Children of all ages – even older children and teenagers, who are routinely expected to make important decisions about other aspects of their lives – are not being consulted. Worryingly, children might feel completely ignored, even invisible, and that their views aren’t valued. They clearly need greater, more meaningful levels of involvement. The Pathfinder model offers the opportunity for change; wider role out would result in universal provision for children to participate, at the start of proceedings.”

Dr Claire Hargreaves, senior research associate at Lancaster University, said:

“For many years, concerns have been raised that current structures do not allow us to ‘hear’ children well enough in private law proceedings, with their input coming too infrequently and too late. This study raises further questions about whether the system is meeting the needs of children and promoting their rights. Further research is needed to understand more about children’s experiences when they do participate in decision making – including the extent to which their views are listened to and acted on and how children from different ethnic groups experience participation.”

The research was based on Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru anonymised, population-level administrative data on all children involved in a private family law case that included a section 8 application and started between January 1 and December 31 2019 – 62,732 children in England and 4,293 children in Wales. Children’s participation was studied over a three-year period from the date the case started. Four main markers of participation, derived from the administrative data, were taken as an indication that a child was directly consulted: a Cafcass section 7 welfare report/Cafcass Cymru Child Impact Analysis, a local authority section 7 welfare report, a local authority section 37 report, or a Rule 16.4 guardian appointment.