About

This report by the Family Justice Data Partnership a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University exposes the heightened socioeconomic and health vulnerabilities of women and men involved in private law proceedings in Wales between 2014/15 and 2019/20.

The research team analysed anonymised linked healthcare (GP and hospital admissions) and private law (Cafcass Cymru) data for 18,653 adults involved in their first private family law application, either as an applicant or a respondent, between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2020.

Findings were compared to a group of 186,470 adults in the general population of Wales with similar demographic characteristics,

matched on age, gender, local authority and deprivation quintile.

Within the cohort group:

- 94% were parents, and mostly involved in an application for a child

arrangements order - men were more likely to be applicants (73%), and women more likely to be respondents (68%)

- 84% were involved in an application between two parents the remainder of the cases involved one or more non-parents

- almost a third of adults lived in the most deprived areas of Wales.

What are ‘private law children cases’ of ‘proceedings’?

Where parents (or other carers) cannot agree arrangements for children, an application can be made to the court under the Children Act 1989. The majority of applications are made by parents for a child arrangement order following separation, but there are a range of other orders available for different circumstances.

Introduction

Private law children cases relate to disagreements or disputes, usually

between parents after relationship breakdown (although they may involve grandparents or other family members), about arrangements for a child’s upbringing, such as where a child should live and/or who they should see.

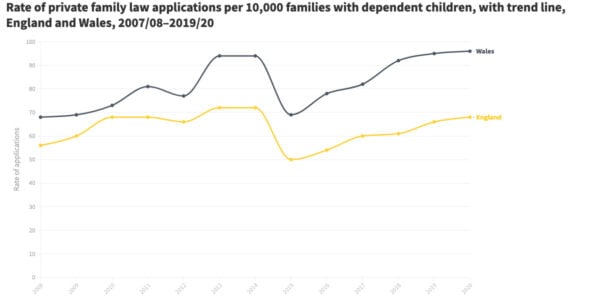

Currently, the evidence base to inform policy and practice in England

and Wales is much less developed for private than public family law, even

though there are more than twice as many private law cases each year than public law (or child protection) cases. Through the use of population-level data, the Uncovering Private Family Law series—researched by the Family Justice Data Partnership, a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University— aims to help address this deficit.

Earlier reports in the series started to develop a demographic profile of the families involved in private law proceedings, including levels of deprivation, the patterns of orders applied for, and the proportion of repeat applications, in both Wales and England.1

The report on which this summary is based extends this work by providing an in-depth look at the pre-court needs and vulnerabilities of the adults involved with the aim of helping to inform policy and practice and enable appropriate system reform, both within and outside the court.

The research team analysed anonymised linked healthcare (GP and hospital admissions) and private law (Cafcass Cymru) data for 18,653 adults involved in their frst private family law application, either as an applicant or a respondent between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2020. Findings were compared to a comparison group of 186,470 adults in the general population of Wales with similar demographic characteristics, matched on age, gender, local authority and deprivation quintile.

- The majority of adults in the cohort group were parents (94%), mostly involved in an application for a child arrangements order.

- Men were more likely to be applicants (73%), and women more likely to be respondents (68%) in the first application they were involved in.

- 84% of the adults were involved in an application between two parents; the remainder of the cases involved one or more non-parents.

- Almost a third of adults lived in the most deprived areas of Wales.

Key findings

This study can only present on issues that were both known to healthcare practitioners and coded into patient records within the study period. As such the figures presented are likely to be underestimates for both the cohort and comparison groups.

Healthcare use

Adults involved in private law applications had higher levels of health service use in the year prior to proceedings than their peers in the comparison group—differences were greatest for emergency or unplanned care.

- Around a quarter (26%) of both men and women in a private law application had an emergency department attendance, compared with 16% in the comparison group.

- 12% of women and 7% of men in the cohort group had an emergency hospital admission—almost double the rate of the comparison group (6% and 4% respectively).

Mental health

Both men and women involved in private law proceedings had higher levels of mental health problems than their peers.

- More than 4 in 10 women (41.7%) and 3 in 10 men (31.2%) in the cohort group had at least one mental health-related GP contact or hospital admission in the year prior to court—this represents one and a half

times the level for men and women in the comparison group. - Common mental health conditions were between two and a half and three times more likely among adults involved in a private law application. In the year prior to proceedings, 13% of women and 9% of

men had a diagnosis of depression, with 12% and 7% respectively having a diagnosis of anxiety. - Although only small numbers of adults involved in private law proceedings had diagnoses of more serious mental illnesses, the prevalence of bipolar disorder (for men and women) and schizophrenia (for women only) was at least twice as high as in the comparison group.

- Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders, personality disorders and eating disorders was also higher among adults involved in private family law—with levels between one and a half and two and a half times those in the comparison group.

Substance use

Known substance use—indicative of problem, harmful or hazardous use of alcohol and/or drugs—was higher in the group of adults involved in private law proceedings.

- Based on combined GP and hospital admission records, substance use was recorded for 2.6% of cohort women and 2.8% of men in the year prior to proceedings—over three times the rate of women and approaching twice the rate of men in the comparison group.

- The relative difference is even more marked for hospital records of substance use. Women in the private law cohort were five and a half times more likely to have a hospital record for substance use and men were three and a half times more likely than the comparison group.

Self-harm

Men and women in private law proceedings were more likely to have had an episode of self-harm than their peers.

- In the year leading up to court proceedings, 1.7% of women and 1.5% of men had at least one episode of self-harm recorded in their GP records—rates between four and five times higher than the comparison group.

Domestic violence and abuse

In the year prior to proceedings, 4% of women in the cohort group

had exposure to domestic violence and abuse recorded in their GP records—20 times the rate of women in the comparison group (0.2%). 2

- Although proportionally very low, women in the cohort group were also more than 11 times as likely to have a domestic violence and abuse related hospital admission (0.24%, compared with 0.02%).

Men in both the cohort and comparison groups were less likely than women to have exposure to domestic violence and abuse recorded—but the disparity between the two groups was greater than for women.

- Men in the cohort group were almost 30 times more likely to have exposure to domestic violence and abuse recorded in their GP records in the year prior to proceedings than those in the comparison group (1.3% compared to 0.05%) and almost 17 times more likely to have a domestic violence and abuse-related hospital admission (0.1% compared to 0.007%).

Data gaps and limitations

The authors acknowledge the following limitations.

- Studies based on administrative data are necessarily limited by the

scope and quality of available data, collected primarily for non-research

purposes. The Cafcass Cymru database records the extent of its

involvement in a case, which in private law often ends at the first hearing, unless concerns exist over child welfare and the court has directed further work or has decided to appoint a children’s guardian under 16.4 of the Family Procedure Rules. In addition, this data source does not record directly who a child is living with at the time an application is made, nor whether or not there are safeguarding issues, such as domestic abuse. - Demographic profiling is limited by the availability of data on

demographic characteristics. For example, neither the Cafcass Cymru nor the health data used in this study records ethnicity or religion. The Welsh Longitudinal General Practice (WLGP) data contains GP records for patients registered with a GP in approximately 80% of practices that supply data to the SAIL Databank. As such, information for GP-based measures was not available for all adults in the cohort or comparison groups. Measures were calculated using the same method for both groups and therefore the comparisons remain valid, although we recommend any more detailed analyses should investigate thisfurther.

References

Barnett, A. (2020). Domestic abuse and private law children cases: A literature review. London: Ministry of Justice Analytical Services.

Bedston, S., Pearson, R., Jay, M.A., Broadhurst, K., Gilbert, R., and Wijlaars, L. (2020). Data Resource: Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) public family law administrative records in England. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(1).

Blackwell, A. and Dawe, F. (2003). Non-resident parental conflict. London: Office for National Statistics.

Cafcass/Women’s Aid. (2017) Non-resident parental conflict. London: Office for National Statistics

Carr, M.J., Ashcroft, D.M., Kontopantelis, E., Awenat, Y., Cooper, J., Chew-Graham, C. et al. (2016). The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001 2013. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1).

Cusworth, L., Bedston, S., Trinder, L., Broadhurst, K., Pattinson, B., Harwin, J. et al. (2020) Who’s coming to court in England? London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory

Cusworth, L., Bedston, S., Alrouh, B., Broadhurst, K., Johnson, R.D., Akbari, A. et al. (2021). Uncovering private family law: Who’s coming to court in England? London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory

Dheensa, S. (2020). Recording and sharing information about domestic violence / abuse in the health service. Bristol: Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol.

Drinkwater, J., Stanley, N., Szilassy, E., Larkins, C. and Hester, M. (2017). Juggling confidentiality and safety : British Journal of General Practice, 67(659).

Family Solutions Group. (2020). “What about me?” Reframing Support for Families following Parental Separation (Subgroup of the Private Law Working Group).

Ford, D. V, Jones, K.H., Verplancke, J.P., Lyons, R.A., John, G., Brown, G. et al. (2009). The SAIL Databank: Building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 9.

Harding, M. and Newnham, A. (2015). How do county courts share the care of children between parents? Family Law, 45(9).

Holt-Lunstad, J., Birmingham, W. and Jones, B.Q. (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2).

Hunt, J. and Macleod, A. (2008). Outcomes of applications to court for contact orders after parental separation or divorce. London: Ministry of Justice

Jackson, J., Lewis, N. V., Feder, G.S., Whiting, P., Jones, T., Macleod, J. et al. (2019). Exposure to domestic violence and abuse and consultations for emergency contraception: Nested case-control study in a UK primary care dataset. British Journal of General Practice, 69(680).

Jay, M.A., Pearson, R., Wijlaars, L., Olhede, S. and Gilbert, R. (2019). Using

administrative data to quantify overlaps between public and private children law in England: Report for the Ministry of Justice on the Children in Family Justice Data Share pilot. London: University College London.

Johnson, R.D., Ford, D. V., Broadhurst, K., Cusworth, L., Jones, K., Akbari, A. et al. (2020). Data Resource: population level family justice administrative data with opportunities for data linkage. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(1).

Johnson, R.D., Alrouh, B., Broadhurst, K., Ford, D.V., John, A., Jones, K. et al. (2021). Health vulnerabilities of parents in care proceedings in Wales. London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory.

Johnson, R.D., Griffiths, L.J., Hollinghurst, J.P., Akbari, A., Lee, A., Thompson, D.A. et al. (2021). Deriving household composition using population-scale electronic health record data-A reproducible methodology. PLoS ONE, 16.

Jones, K.H., Laurie, G., Stevens, L., Dobbs, C., Ford, D. V., and Lea, N. (2017). The other side of the coin: Harm due to the non-use of health-related data. International journal of medical informatics, 97.

Jones, K.H., Ford, D.V., Thompson, S., and Lyons, R.A. (2020). A profile of the SAIL databank on the UK secure research platform. International Journal of Population Data Science, 4(2).

Lader, D. (2008). Non-resident parental conflict 2007/08. Omnibus Survey Report No. 38. Newport: Office for National Statistics.

Lyons, R.A., Jones, K.H., John, G., Brooks, C.J., Verplancke, J.P., Ford, D. V. et al. (2009). The SAIL databank: Linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 9(1).

Marchant, A., Turner, S., Balbuena, L., Peters, E., Williams, D., Lloyd, K. et al. (2020).Self-harm presentation across healthcare settings by sex in young people: An ecohort study using routinely collected linked healthcare data in Wales, UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 105(4).

McFarlane, A. (2019). View from the President’s Chambers [online] Available from: https://www.familylaw.co.uk/news_and_comment/1st-view-from-the-president-schambers-the-number-one-priority .

McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., and Brugha, T. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital.

Ministry of Justice. (2020a). Family court statistics quarterly, England and Wales, January to March 2020. London: Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice. (2020b). Assessing risk of harm to children and parents in private law children cases final report. London: Ministry of Justice.

Moorhead, R. and Sefton, M. (2005). Litigants in person: Unrepresented litigants in first instance proceedings. London: Department for Constitutional Affairs.

Morgan, C., Webb, R.T., Carr, M.J., Kontopantelis, E., Chew-Graham, C.A., Kapur, N. et al. (2018). Self-harm in a primary care cohort of older people: incidence, clinical management, and risk of suicide and other causes of death. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(11).

NICE. (2004). Self-harm in over 8s: short-term management and prevention of recurrence. NICE Clinical Guidance CG16.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2012). Statistical bulletin 2011: Census, population and household estimates for small areas in England and Wales.

ONS. (2018). Domestic abuse in England and Wales: year ending March 2018.

ONS. (2019). Domestic abuse in England and Wales overview November 2019.

Olive, P. (2018). Intimate partner violence and clinical coding: Issues with the use of the international classification of disease (ICD-10) in England. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 23(4).

Peacey, V. and Hunt, J. (2008). Problematic contact after separation and divorce? A national survey of parents. London: Nuffield Foundation and One Parent

Famlies/Gingerbread.

Private Law Working Group. (2019). A review of the child arrangement programme [PD12B FPR 2010]. Report to the President of the Family Division. London: High Court of Justice.

Private Law Working Group. (2020a). Private law: Family disputes – the time for change, the need for change, the case for change. Second report to the President of the Family Division. London: High Court of Justice. Private Law Working Group. (2020b). Private Law Advisory Group final report. London: High Court of Justice.

Rees, S., Watkins, A., Keauffling, J. and John, A. (2020). Incidence, mortality and survival in children and young people aged 11-25 in Wales with co-occurring mental disorders and problem, hazardous or harmful substance use: estimates derived from linked routine data. Research Square (preprint).

Reilly, S., Olier, I., Planner, C., Doran, T., Reeves, D., Ashcroft, D.M. et al. (2015).Inequalities in physical comorbidity: A longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open, 5(12).

Richardson, J., Coid, J., Petruckevitch, A., Chung, W.S., Moorey, S. and Feder, G. (2002). Identifying domestic violence: cross sectional study in primary care. British Medical Journal, 324(7332).

Rodgers, S.E., Lyons, R.A., Dsilva, R., Jones, K.H., Brooks, C.J., Ford, D. V. et al. (2009). Residential Anonymous Linking Fields (RALFs): A novel information infrastructure to study the interaction between the environment and individuals’ health Journal of Public Health, 31(4).

SafeLives. (2021). Understanding court support for victims of domestic abuse. London: Domestic Abuse Commissioner.

Saini, M. and Birnbaum, R. (2017) Unraveling the label of ‘high conflict’: What factors really count in divorce and separated families. Journal of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies 51 (1)

Santini, Z.I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S. and Haro, J.M. (2015). The association of relationship quality and social networks with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among older married adults: Findings from a cross-sectional analysis of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Journal of affective disorders, 179.

Springate, D.A., Kontopantelis, E., Ashcroft, D.M., Olier, I., Parisi, R., Chamapiwa, E. et al. (2014). ClinicalCodes: An online clinical codes repository to improve the validity and reproducibility of research using electronic medical records. PLoS ONE, 9(6).

Trinder, L., Hunter, R., Hitchings, E., Miles, J., Moorhead, R., Smith, L. et al. (2014). Litigants in person in private family law cases. London: Ministry of Justice.

Truant, G.S. (1994). Personality diagnosis and childhood care associated with adult marital quality. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 39(5).

Webb, C., Pio, M., Hughes, S., Jones, E., Dzhumerska, V., Lesniewska, M., et al. (2020). Pathfinder toolkit. Enhancing the response to domestic violence across healthcare settings. London: SafeLives.

Whisman, M. and Uebelacker, L. (2003). Comorbidity of relationship distress and mental and physical health problems. In D. Snyder and M. Whisman, eds. Treating difficult couples: healping clients with coexisting mental and relationship disorders. New York: The Guildford Press, pp. 3

Whisman, M.A. and Schonbrun, Y.C. (2009). Social consequences of borderline personality disorder symptoms in a population-based survey: marital distress, marital violence, and marital disruption. Journal of personality disorders, 23(4). Williams, T. (2018). What could a public health approach to family justice look like? London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory.

Woodman, J., Sohal, A.H., Gilbert, R. and Feder, G. (2015). Online access to medical records: finding ways to minimise harms. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 65(635).

World Health Organization. (2012). Violence against women: intimate partner and sexual violence against women.

-

Lancaster University

Lancaster University -

Family Justice Data Partnership

Family Justice Data Partnership -

SAIL Databank

SAIL Databank -

Population Data Science at Swansea University

Population Data Science at Swansea University -

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research -

Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform

Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform -

Swansea University Medical School

Swansea University Medical School