Introduction

A child’s right to participate and have their voice heard in private law proceedings is acknowledged in legislation and guidance – both as a way of informing welfare-based decisions and upholding their rights. This report looks at what the data tells us about the ways in which children participate and how often.

Children involved in private law cases are not automatically party to proceedings as they would be in public law cases (care proceedings). They have been described as ‘by and large, completely invisible in court’ (Munby 2015), with their voices going unheard or ‘muted’ (Ministry of Justice 2020).

A recent review of international research on children’s experiences of parental separation and court proceedings concluded that children overwhelmingly feel unheard, and that they have a limited understanding of the court process, the role of lawyers and judges, and their right to be heard (Roe 2021).

Research on children’s experiences of private law proceedings in England and Wales – and data about how they are involved and the extent of that involvement – is limited. It is important to understand how the current system is engaging children, and where improvements are needed.

This study is the first to use administrative data recorded and held by the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) to investigate the proportion of private law cases that children are likely to have directly participated in.

The report examines the proportion of private law cases that had a section 7 report (either from Cafcass or the localauthority), a section 37 report, and/or a rule 16.4 appointment recorded in the administrative data within 12 months of the case start date. These markers all indicate that, depending on their age and understanding, children will have been directly consulted on their wishes and feelings by a family court adviser, local authority social worker, or a guardian. The study then reflects on these findings, highlighting the limitations of the data and how this might be improved, and the implications for children, their families and the family justice system.

Findings

The study sample included 40,753 private family law cases that included a section 8 application that started in 2019/20. The following sections present an analysis of the proportion of these cases where children might have been directly consulted or participated in the 12 months after the case commenced using the four participation markers described above.

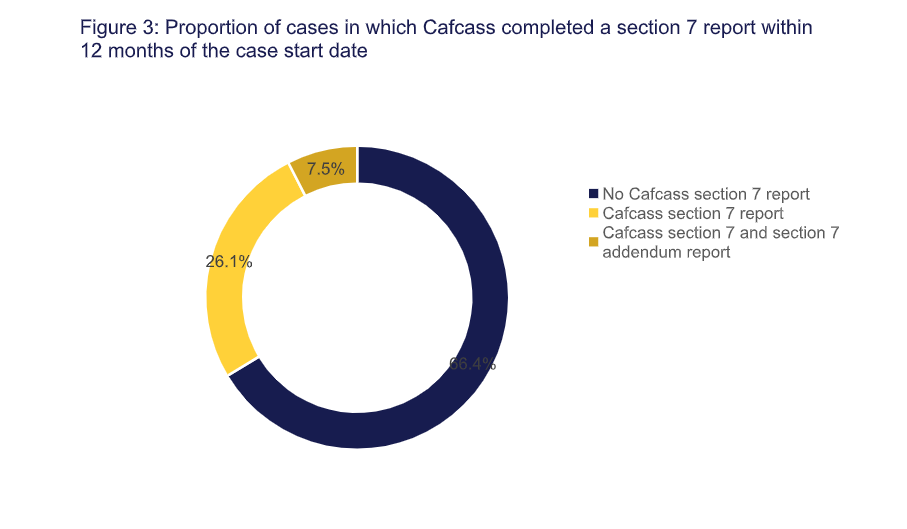

Section 7 welfare report (Cafcass)

The most common indication that children are likely to have had their views sought directly is through Cafcass being instructed by the court to undertake a welfare report. As shown in Figure 3 , a section 7 report was completed by Cafcass within 12 months of the case start date in around a third (13,708, 33.6%) of cases. In a small proportion of these cases, 7.5% (3,073), an addendum section 7 report was also filed.

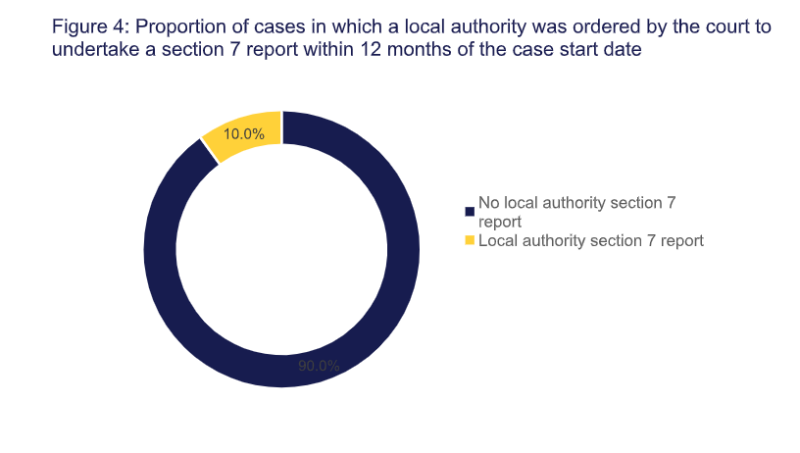

Section 7 welfare report (local authority)

As shown in Figure 4 , a local authority was ordered by the court to undertake a section 7 report in 10% (4,067) of private law cases that started in 2019/20.

While this direction is recorded in the Cafcass data when Cafcass is present at the relevent hearing, it is important to note that in most instances where a local authority becomes involved in a private law case, Cafcass ceases its involvement and thus recording of data –so these figures may be an underestimate.

While we might know that a local authority was ordered to prepare a report, no information is available on whether and when it was filed, what it said, or what happened next in the case.

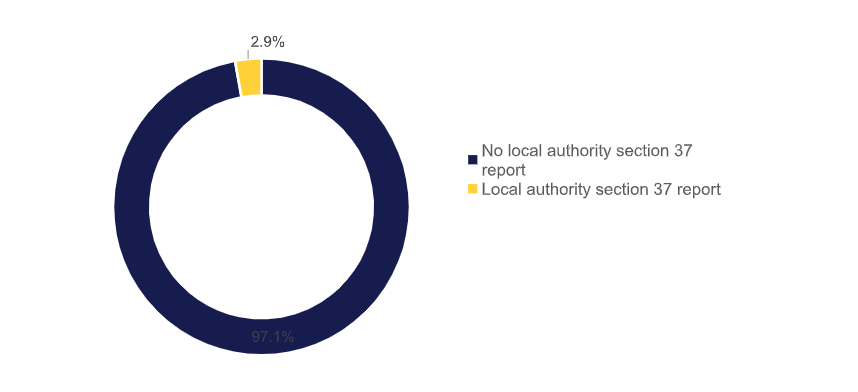

Section 37 report

The court directed the local authority to investigate whether it might be appropriate for care proceedings to be issued in 2.9% (1,168) of private law child arrangements cases that started in 2019/20, as seen in Figure 5.

Again it is worth stressing that we have no information on the findings of this section 37 report.

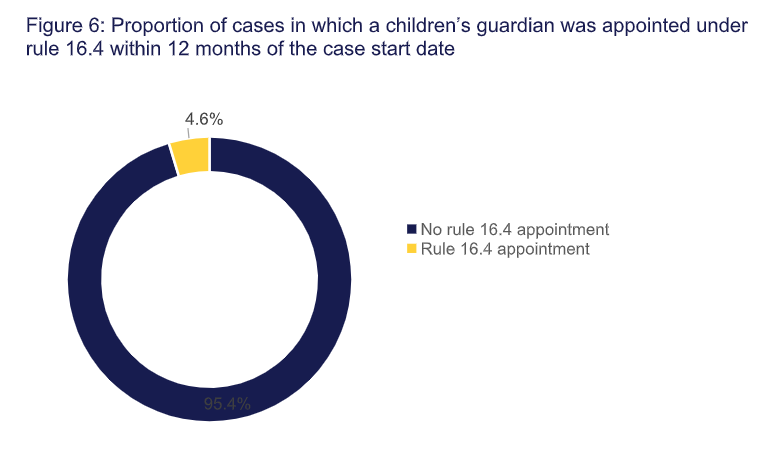

Rule 16.4 (guardian appointment)

As shown in Figure 6 , it is recorded that the judge made the child(ren) party to proceedings in around one in 20 cases (1,881, 4.6%), appointing a children’s guardian under rule 16.4 within 12 months of the case starting.

A Cafcass guardian was appointed in 4.5% (1,825) of cases and a NYAS guardian was appointed in 0.1% (48) of cases. In a very small number of cases (fewer than 5), it was recorded that the child had appointed their own solicitor.

Cafcass might not always record appointments to external parties, instead recording ‘no further work for Cafcass’ – thus figures may be an underestimate.

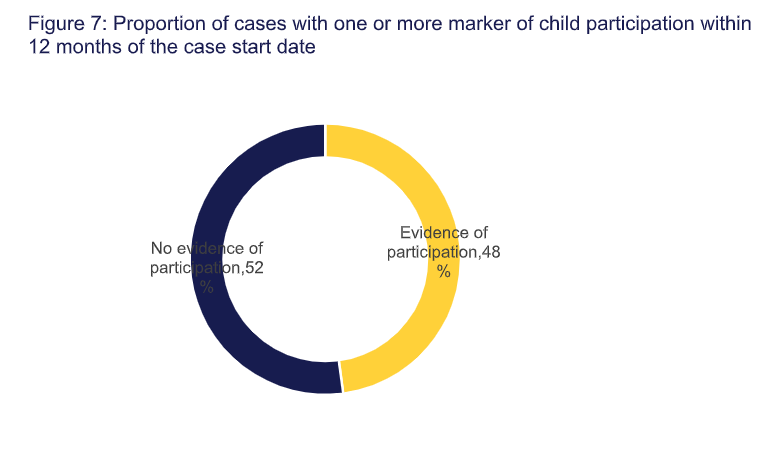

Overall indication of a child’s involvement

A case might include one or more of the above markers that children might be expected to have been consulted directly or participated. Almost half (19,532) of child arrangement cases that started in 2019/20 had one or more Cafcass (section 7) welfare report, section 7 or section 37 report by the local authority, or rule 16.4 guardian appointment, within 12 months of the case start date. Again it is worth reiterating that although we have used these as indications of children’s participation, we cannot know that all the children will have been directly involved, or the quality or duration of that involvement. Equally, as mentioned above, children may have participated in ways not recorded in the Cafcass administrative data.

Reflections

The national and international legislation and guidance sets the context for a family justice system where child engagement and participation are the default, both as a way of informing welfare-based decisions and upholding children’s rights. By bringing together data on a number of markers where children might have been consulted directly during private law proceedings, this report intends to start to capture the extent of children’s engagement and to provide a foundation for future research.

The data analysed for this study suggests that children formally participate in less than half of private law cases. This means that, in the majority of cases, they have no (or very limited) opportunity to have their voices heard while the court makes important decisions about their future. This may be because the children were considered too young, although this in turn raises questions about the age at which it is appropriate for children to participate. Given the lack of a clear consensus, further work is needed to explore this – particularly given that the wider evidence base suggests children largely want to be involved in decision making (Roe 2021).

In terms of what the analysis tells us more generally about private law cases, it is worth noting that the markers used to indicate children’s engagement – Cafcass section 7 report, local authority section 7 report, local authority section 37 report and rule 16.4 guardian appointment – might suggest that there are welfare concerns necessitating in-depth exploration of the circumstances of the child and family. Just under half of cases required one or more of these interventions in the first year. This adds to an emerging body of evidence that highlights the complexity of private law cases and needs of families coming through the private law courts. Estimates of the prevalence of allegations of domestic abuse range from 49% to 62% of cases (see Barnett 2020). In addition, a recent study of Cafcass Cymru data linked with health data demonstrated that adults in private law proceedings in Wales had significantly higher levels of GP appointments and hospital admissions for mental health, substance misuse and domestic abuse than a comparable group of adults (Cusworth et al. 2021b).

A new approach to dealing with cases involving disputes between parents over arrangements for their children is being tested in the Pathfinder pilot sites in Dorset and North Wales. One of the aims for the Pathfinders is to amplify the voice of the child within proceedings, including through the preparation of a child impact report before first hearing. This involves direct or indirect (for example, via digital means or through a third-party) engagement with the child to determine their circumstances, preferences for engagement and initial wishes and feelings at the outset of proceedings. The evaluation of these pilots, and in particular the level and nature of children’s engagement under the new arrangements, will be another valuable contribution to the growing evidence base around children’s engagement in and experience of proceedings.

It is important to highlight the limitations to the use of the Cafcass administrative data to study children’s involvement (see ‘Data gaps and limitations’ in Introduction of full report). However, there is an obvious commitment by Cafcass to making improvements in the recording of data when its practitioners meet and engage with children. This includes markers of participation – such as where a Re W report has been prepared (to assist in deciding whether a child should give evidence), and the increased use of a specific ‘child seen’ table – which it started to record systematically in 2020. The child seen table contains information on direct engagement between Cafcass practitioners and the child(ren) in a case, and the mode of engagement, for example, at school, at home, by video call or sending a letter. Systematic recording of this data is in its infancy, and thus robust analysis was not possible at the current time, but will be useful in the future.

There are also a number of other important ways in which children might engage with proceedings that are not currently recorded systematically in the administrative data. It would be useful moving forwards for systematic data collection within the family justice system to include, for example, children writing to or meeting with the judge, giving evidence, engaging with experts such as psychologists and independent social workers, and the use of child-friendly judgments. Some of this data collection may need to sit outside of Cafcass, where for example they cease to be involved in the case before the case itself has concluded, but at a system level there is a need for reliable, detailed data that gives us a better understanding of how children engage and participate as they journey through the system.

Despite the limitiations, the novel findings reported here are important, and begin to paint a picture of children’s involvement in private law cases. There is an ongoing need to develop this area of research so that the family justice system has a greater understanding of how and when children’s views are currently sought and represented. This enhanced knowledge is needed to inform more tailored policy and practice responses, and to ensure that children have the opportunity for their voices to be heard and considered in all legal proceedings that affect them.

References

Barnett, A. (2020). Domestic abuse and private law children cases: A

literature review. Ministry of Justice.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploa

ds/attachment_data/file/895175/domestic-abuse-private-law-children-

cases-literature-review.pdf

Bedston, S., Pearson, R., Jay, M.A., Broadhurst, K., Gilbert, R. and

Wijlaars, L. (2020). Data Resource: Children and Family Court Advisory

and Support Service (Cafcass) public family law administrative records in

England. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(1).

https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1159

Cusworth, L., Bedston, S., Alrouh, B., Broadhurst, K., Johnson, R.D.,

Akbari, A. and Griffiths, L.J. (2021a). Uncovering private family law: Who’s

coming to court in England? Nuffield Family Justice Observatory.

https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/private-family-law-whos-coming-to-

court-england

Cusworth, L., Hargreaves, C., Alrouh, B., Broadhurst, K., Johnson, R.,

Grifths, L., Akbari, A., Doebler, S. and John, A. (2021b). Uncovering

private family law : Adult characteristics and vulnerabilities (Wales).

Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-

content/uploads/2021/11/nfjo_private-

law_adults_report_eng_final_20211110-1.pdf

Ford, D. V, Jones, K.H., Verplancke, J.P., Lyons, R.A., John, G., Brown,

G., Brooks, C.J., Thompson, S., Bodger, O., Couch, T. and Leake, K.

(2009). The SAIL Databank: Building a national architecture for e-health

research and evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 9.

https://doi.org/10.1186%2F1472-6963-9-157

Jones, K.H., Ford, D. V., Jones, C., Dsilva, R., Thompson, S., Brooks, C.J.,

Heaven, M.L., Thayer, D.S., McNerney, C.L. and Lyons, R.A. (2014). A

case study of the secure anonymous information linkage (SAIL) gateway:

A privacy-protecting remote access system for health-related research and

evaluation. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 50.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.01.003

Jones, K.H., Ford, D.V., Thompson, S. and Lyons, R.A. (2020). A profile of

the SAIL databank on the UK secure research platform. International

Journal of Population Data Science, 4(2).

https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v4i2.1134

Ministry of Justice. (2020). Assessing risk of harm to children and parents

in private law children cases. Final report.

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/assessing-risk-of-harm-to-

children-and-parents-in-private-law-children-cases

Munby, J. (2015). Unheard voices: the involvement of children and

vulnerable people in the family justice system. The annual lecture of The

Wales Observatory on Human Rights of Children and Young People,

Uncovering private law: What does the data tell us about children’s participation?

Swansea University, 25 June. https://www.swansea.ac.uk/media/2015-

Observatory-Annual-Lecture-SIR-JAMES-MUNBY.pdf

Roe, A. (2021). Children’s experience of private law proceedings: six key

messages from research. Spotlight series. Nuffield Family Justice

Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/childrens-experience-

of-private-law-proceedings-six-key-messages-from-research

-

Family Justice Data Partnership

Family Justice Data Partnership -

Lancaster University

Lancaster University -

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research -

Swansea University Medical School

Swansea University Medical School -

Population Data Science at Swansea University

Population Data Science at Swansea University -

SAIL Databank

SAIL Databank