Summary

This summary highlights the main findings of the second report in the Uncovering Private Family Law series. The research was carried out by the Family Justice Data Partnership—a collaboration between the University of Lancaster and the University of Swansea.

Disputes between parents over child arrangements following family separation make up a significant proportion of cases within the family justice system. There is concern about the level of private law demand in England and Wales, with a perception that too many parents are becoming over-reliant on the courts to resolve personal disputes (Private Law Working Group 2019; McFarlane 2019).

This summary highlights the main findings of the second research report in the Uncovering Private Law series, which aims to build a profile of families in private law proceedings, and their pathways and outcomes.

The report uses population-level data to examine trends in demand in England, both nationally and by region, and develops a demographic profile of the families involved, including levels of deprivation, the patterns of orders applied for, and the proportion of repeat applications. In doing so, it enables us to better understand the characteristics, needs and vulnerabilities of the families involved in private law cases.

What are ‘private law children cases’ or ‘proceedings’?

Where parents (or other carers) cannot agree arrangements for their children, one or both may make an application to the court for an order under the Children Act 1989. There are a range of orders available for different circumstances. The most common is a child arrangements order (CAO), which is to regulate arrangements relating to where a child should live and/or who they should see.

Where did the data come from?

The data in the report is based on administrative data collected routinely by Cafcass (the organisation that represents children’s best interests in family justice proceedings in England) and available in the privacy-protecting SAIL (Secure Anonymised Information Linkage) Databank, hosted by Swansea University (Ford et al. 2009; Jones et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2019). It uses population-level data on all private law applications made to the family court in England between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2020, together with publicly available Office for National Statistics (ONS) family estimates (Office for National Statistics 2019) and indices of deprivation (Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government 2019).

Information about the legal orders applied for— and the applicants, respondents, and subjects involved—were included for applications issued between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2020. Analysis of volumes and rates of applications, across England as a whole and in each of the nine English regions, was based on all private law applications. We also profiled the adults and children involved in standard parental applications, including demographic characteristics, deprivation, the orders being applied for, and returns to court.

The report presents the first independent analysis of population-level private family law data held by Cafcass, based on a total sample of almost 546,000 applications issued between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2020 in England.

Key research findings

The evidence base to inform policy and practice in England and Wales is much less developed for private than public family law, even though there are more than twice as many private law cases each year.

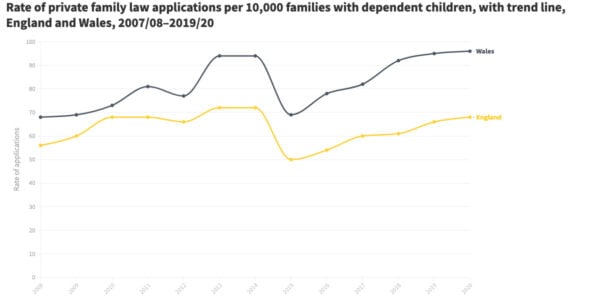

In this research on England our findings are largely consistent with those reported in Uncovering private family law: Who’s coming to court in Wales? (Cusworth et al. 2020), indicating marked similarities between the two jurisdictions. The report confirms findings from previously published research on England, while also adding new insights, based on population-level data.

In keeping with previously published research, the majority of private law cases are between two parents, and are mainly brought by fathers, usually the non-resident parent, and concern a single child who is most often aged between one and nine years old. The private law adult population are mainly in their late twenties and thirties.

The trend in the volume of private law applications has been modestly upwards over the period (2007/08 to 2019/20), although overall use of the court remains low

- In 2007/08, there were around 35,000 applications. This rose to around 48,000 in 2012/13 and 2013/14, before falling significantly after legal aid changes were introduced in 2013. The number of applications has now almost recovered to previous levels, with 46,500 applications made in 2019/20.

- The removal of legal aid entitlement (except for certain cases involving domestic abuse) appears to have mainly delayed or paused applications, rather than reducing the levels of need for assistance over the longer term.

- Less than 0.75% of all families with dependent children in England (including intact and separated families) make a private law application each year, marginally lower than in Wales (less than 1%).

About a quarter of applications are returns to court

- Between 24% and 27% of private law applications between 2013/14 and 2019/20 were made by an applicant who had been involved in a previous application within the last three years.

- Fathers are more likely to be repeat applicants, whereas mothers are more likely to issue their own application after being a respondent on a previous application.

There is a clear link between deprivation and private law applications, which indicates that the economic vulnerability of private law parents requires closer policy attention

- In 2019/20, 29% of applicant fathers and 31% of mothers making a private law application lived in the most deprived quintile (by definition, representing 20% of the wider population), with 52% of fathers and 54% of mothers living in the two most deprived quintiles (representing 40% of the wider population).

- As with public law cases, level of need and trends vary by geographic area. Rates of private law applications were consistently highest in the North East, North West, and Yorkshire and the Humber regions, and consistently lowest in London and the South East.

There is some evidence of a justice gap following legal aid changes

- There was a reduction in the proportion of applications brought by people living in the most deprived areas, by younger applicants, and involving a child under five from 2013/14 onwards. This provides some evidence to support the emergence of a ‘justice gap’, where certain sections of the population can no longer afford to bring private law applications following the removal of legal aid from private law cases in 2013, other than for some survivors of domestic abuse.

The overall private law population is broadly stable, but there are some changes in what is being applied for

- The majority of private law applications continue to be for child arrangements orders (CAOs). However, as a proportion of all applications, this has declined from two-thirds (69%) in 2010/11 to just over half (52%) in 2019/20, and is much lower than that seen in Wales.

- There have been proportional increases in applications for ‘other’ private law orders. The proportion of applications for prohibited steps orders fluctuated between 22% and 26%, with applications for specific issue orders increasing from 7% in 2010/11 to 14% in 2019/20, and those for enforcement orders rising from 3% in 2010/11 to 8% in 2019/20.

- These other orders represent quite a significant shift in the workload for the family justice system towards what may be more challenging or contentious cases. The increase in enforcement applications may reflect greater difficulties with making contact arrangements work, possibly in the post- Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) absence of solicitors who might find other routes to addressing contact difficulties.

- There were substantial differences in the orders applied for by mothers and fathers, with around four of five applications made by fathers concerning child arrangements, compared with just over two in five applications made by mothers.

Data gaps and future priorities

The Uncovering Private Law series aims to develop a comprehensive profile of the children and adults entering the family justice system in England and Wales, their pathways, experiences and outcomes. The current report focuses on an initial demographic profiling of applications in England. It does so by making use of administrative data linkage opportunities in the SAIL Databank. Further priorities for analysis include the following.

- Work to differentiate types of private law cases and pathways of adults and children, including more detailed analysis of returner cases and those where the child is separately represented (known as Rule 16.4 cases). The use of large-scale linked data (health, welfare and further demographic) could shed more light on what might distinguish the profiles of single, repeat, and multiple (or chronic) users. This would enable earlier identification and intervention to prevent what would otherwise be chronic cases from becoming entrenched.

- A more in-depth look at the pre-court needs and vulnerabilities of adults and children, including the prevalence of mental health difficulties, domestic abuse, and other child protection issues. A key priority will be exploring the overlap between public and private law cases.

- Greater exploration of regional and local variations in rates of private law applications, including possible drivers, including levels of deprivation and the availability of mediation and other support services.

- A deeper dive into different case types, particularly the non-standard cases about which there is very little prior research: those with two or more applicants and/or two or more respondents, and those including orders other than those for child arrangements.

Recommendations

This programme of work on private family law is still at an early stage, but there are several clear implications for policy makers and service providers at this point.

- As was seen in Wales (Cusworth et al. 2020), this research has established that there is an over-representation in private law of adult parties living in more deprived areas. It is critical that policy makers consider the role of deprivation as a factor in private law cases and its interaction with other factors such as conflict, domestic abuse and other child protection issues. This will be an important step in informing, and possibly reshaping, the response to private law need in both the court and out-of-court context.

- Regional variation in rates of private law applications is not insignificant, and this requires greater evaluation of the provision, uptake and effectiveness of mediation and other support services, and other possible drivers of these differences, including local-level deprivation. Policy responses to court demand need to take into account local need for assistance.

- The evidence of a justice gap following the legal aid reforms is perhaps not as pronounced as in Wales, although there has been a reduction in applications by applicants who are younger, and living in more deprived areas of England. We suggest that the Ministry of Justice reviews this evidence, alongside other research and analysis, to reflect on whether access to justice is being inhibited and what steps can be taken to address this.

- The majority of private law proceedings involve a single child or two siblings. Sibling support is a well-documented resilience factor for children that will be missing in large numbers of private law cases. In addition to addressing the dispute between adults, the research highlights the importance of making support available for children. This is particularly important given the recent focus on enabling the child’s voice to be heard in private law cases (Family Solutions Group 2020; Ministry of Justice 2020).

The Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) database is designed to meet operational requirements, rather than for research purposes. However, various improvements could be made to the quality and scope of the data, with minimal time and resource costs, that would enhance its potential for generating evidence to improve service provision. We particularly recommend recording a child’s living arrangements at the time of application, and whether there are allegations of domestic abuse and other safeguarding concerns.

Reference list

Cusworth, L. et al. (2020). Who’s coming to court? Private family law applications in Wales. London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory.

Family Solutions Group. (2020). “ What about me ?” Reframing Support for Families following Parental Separation (Subgroup of The Private Law Working Group).

Ford, D. V. et al. (2009). The SAIL Databank: Building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 9.

Jones, K.H. et al. (2014). A case study of the secure anonymous information linkage (SAIL) gateway: A privacy-protecting remote access system for health-related research and evaluation. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 50.

Jones, K.H., Ford, D.V., Thompson, S., and Lyons, R. (2019). A Profile of the SAIL Databank on the UK Secure Research Platform. International Journal of Population Data Science, 4(2).

McFarlane, A. (2019). Living in interesting times: Keynote address to Resolution Conference 2019 [online]. Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. Available from: www.judiciary.uk/announcements/speech- by-president-of-the-family-division-to-the- resolution-conference-2019/

Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government. (2019). National Statistics English indices of deprivation 2019.

Ministry of Justice. (2020). Assessing risk of harm to children and parents in private law children cases – Implementation Plan. London: Ministry of Justice.

Office for National Statistics. (2019). Families by family type, regions of England and UK constituent countries.

Private Law Working Group. (2019). A review of the Child Arrangement Programme [PD12B FPR 2010]. London: Report to the President of the Family Division, High Court of Justice.

Complete list of references available from the full report.

Organisations

-

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research -

Lancaster University

Lancaster University -

Population Data Science at Swansea University

Population Data Science at Swansea University -

SAIL Databank

SAIL Databank