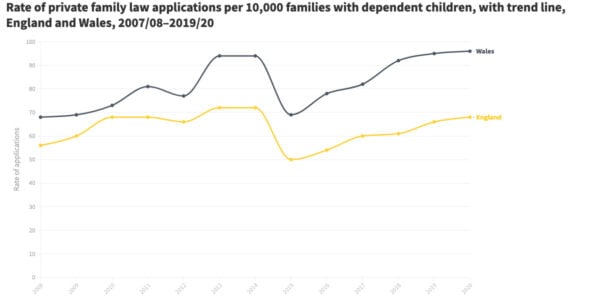

Private law applications to the family court usually involve separated parents who are struggling to agree arrangements for their children1,2. However, 10 per cent of these applications each year feature people who aren’t parents. New research published by Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO) explores the types of orders being applied for and the characteristics of the people involved. It highlights that this minority of cases is actually a very sizeable group, with around 5,500 such applications made each year in England and 300 in Wales – equivalent to around a third of the volume of public law applications for a care or supervision order.

The study, carried out by the Family Justice Data Partnership – a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University – investigated private law applications involving non-parents in England and Wales over a four-year period (2017/18 to 2020/21).

It shows a diversity in terms of non-parents involved in applications, including grandparents, aunts and uncles, siblings, step-parents, special guardians, foster carers, intended parents in surrogacy cases and putative fathers*. Grandparents accounted for 58 per cent of all non-parents involved in England and 63 per cent in Wales.

A wide variety of orders were applied for, but a clear majority of applications were for a child arrangements order – 56 per cent in England and 59 per cent in Wales. In England (where the data allows a more detailed understanding of the order sought), a high number were applications by extended family members for children to live with them. These applications are in addition to other application types that suggest children are being cared for away from their parents (such as special guardianship orders). The researchers note they are likely to represent situations where there were concerns for children’s safety or welfare and a possible overlap with the circumstances of care cases. The study found a significant proportion of these types of cases – at least 38 per cent, but potentially substantially more.

Apart from child arrangements orders, other orders applied for during the four-year period included special guardianship (7.9 per cent in England and 6.0 per cent in Wales), adoption (16 per cent in Wales), parental responsibility (5.2 per cent in England and 2.2 per cent in Wales) and parental orders in surrogacy cases (5.7 per cent in England and 2.3 per cent in Wales). The research notes the very different circumstances of some of these types of cases.

Overall, applications disproportionately involved people living in the more deprived areas of England and Wales – to a greater extent than in standard private family law applications, where there is also a clear link between deprivation and private law.

The study also revealed that adults from ethnic minority backgrounds in England were less likely to feature in non-parent applications than in applications involving two parents, although data limitations prevented in-depth analysis.

Lisa Harker, director of Nuffield FJO, said: “For some families, taking a private law route may offer a way to find solutions and to formalise arrangements for children without the involvement of children’s services. But for other families, we suspect the reality may be less positive. There may be an overlap between what we might typically see as private law and public law issues, with child protection concerns potentially playing out in the background in private law cases, yet children and families may not be receiving the support they need from the private law courts.

“For example, careful consideration needs to be given to whether children’s views are being heard – as unlike in public law proceedings, children are not automatically separately represented in private cases. Other rights that come with public law proceedings, such as legal aid for parents, are also not given to those in the private law system. This leaves many potentially vulnerable adults without access to adequate legal advice and support in navigating the complexity of the family justice system, including making an application for the most appropriate type of order.”

Dr Linda Cusworth, Lancaster University, was the lead author of the report. She said: “The evidence is much less developed for private than for public law, despite that over three times as many private law cases are started each year in England and Wales than public ones – there were 54,600 new private law cases compared to 16,400 public law cases in 2021, according to the Ministry of Justice. While non-parent cases represent just 10 per cent of private law cases, they involve thousands of people and potentially high levels of need and complexity. Yet, to date, the private law reform agenda has focused on separating parents, overlooking the needs of this wider group of families.

“This is the first population-based study to explore these types of private law applications in England and Wales. We have examined the diversity of applications and the individuals involved, enabling a better understanding of their circumstances to increase the evidence base. We hope this report will promote useful discussions, and help practitioners and policymakers to focus on how best to meet the needs of families.”

Uncovering private family law: Exploring applications that involve non-parents is the sixth in a Nuffield FJO series that aims to help build the evidence base on private law children cases in England and Wales. It used Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru anonymised, population-level administrative data, accessed through the SAIL (Secure Anonymised Information Linkage) Databank at Swansea University.