Introduction

This is the first population-based study to examine the mental health needs of children involved in private law proceedings in Wales.1 It provides an overview of the rates of depression and anxiety in this group over time and makes comparison to a similar group of children who were not involved in proceedings. It summarises findings from a journal article, published in BJPsych Open (Griffiths et al. 2022). The study helps to build a better understanding of the mental health vulnerabilities of children involved in private law cases.

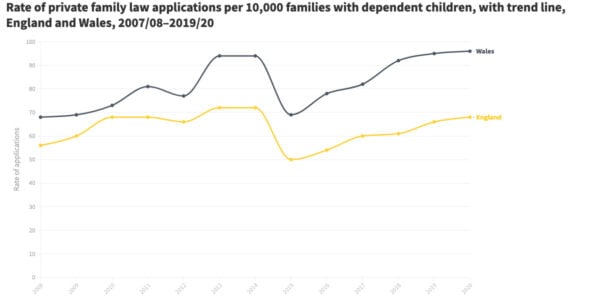

In 2018, 4,530 children were involved in private family law proceedings and, over the last decade, the overall trend in the volume of private law applications has been modestly upwards (Cusworth, Bedston et al. 2020).

Children and families become involved with the family court for a wide variety of reasons. In contrast to public law (or child protection) proceedings that are brought by the local authority, private law applications are triggered by the decisions of private individuals, usually a parent, rather than the state. Private law family court cases are disputes – usually between parents after relationship breakdown – about arrangements for a child’s upbringing, such as where a child should live and/or who they should spend time with. Across England and Wales, 51,658 private law cases were initiated in 2018 (Ministry of Justice 2018). The aim of these cases is to make arrangements for children that promote their welfare; yet, little is known about the health and well-being of children involved with family courts or their long-term outcomes.

The majority of children involved in private family law cases will have experienced parental separation and many will have been exposed to parental conflict. There is very robust evidence that parental conflict that is frequent, intense, poorly resolved and about the child is associated with multiple negative outcomes for children (Grych and Fincham 1990; Harold et al. 2016; Acquah et al. 2017).

We know from previous studies that about half of private law cases in England involve allegations of domestic abuse (Hunt and Macleod 2008; Harding and Newnham 2015; Cafcass/Women’s Aid 2017). Recent research by the Family Justice Data Partnership – a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University – has also shown that domestic abuse, substance use and parental mental ill health are all present at significantly higher rates for families involved in private law proceedings in Wales than in the general population (Cusworth, Hargreaves et al. 2021) and that families living in more deprived areas of England and Wales are overrepresented (Cusworth, Bedston et al. 2020, 2021). Children involved in these proceedings may therefore have been subject to a range of adverse experiences due to these characteristics and vulnerabilities, as well as being exposed to parental conflict. Such experiences are linked to poorer short and longer-term development and mental health (Kerker et al. 2015; Hughes et al. 2017; Harold and Sellers 2018) and with poorer social outcomes, educational achievement, and/or other serious disruptions to lives.

There is some evidence regarding the mental health of children in care (Ford et al. 2007; Baldwin et al. 2019); however, to our knowledge, no previous research in the UK has compared outcomes for children who are in or have been through private law proceedings with the general population using large-scale administrative data. Far better evidence is needed to ensure that mental health needs are understood and taken into account in when making welfare-based decisions. Studies based on population-level data are persuasive in terms of providing policy makers and practioners with robust evidence to shape service development.

In light of this, this study examined depression and anxiety in children who were the subjects of private law children cases in Wales compared to those not involved in family court proceedings.

About private law applications

In contrast to public law (or child protection) proceedings that are brought by the local authority, private law applications are triggered by the decisions of private individuals, usually a parent, rather than the state. Private law family court cases are disputes – usually between parents after relationship breakdown – about arrangements for a child’s upbringing, such as where a child should live and/or who they should spend time with.

About the data

This study used anonymised administrative data supplied by Cafcass Cymru, linked with Welsh GP health data within the SAIL Databank – a highly secure, trusted research environment.

A cohort of all children (n=17,041) involved in private law proceedings in Wales between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2018 was created. Findings were compared to a comparison group (n=680,617) selected from children in the general population of Wales who were not involved in proceedings.

Study limitations

This study only reports on problems both known to the healthcare practitioners and coded into patient records; our figures are therefore likely an underestimate of the true numbers of children with anxiety and depression.

The comparison group of children will likely include some children whose parents have separated but did not use the family courts to resolve parenting disputes, as well as many children whose parents have not separated. It is therefore not possible to draw direct conclusions about the relationship between court proceedings on children’s mental health, as opposed to parental separation.

Key Findings

- The children involved in private law proceedings (‘the private law cohort’) were more likely to experience depression and anxiety than their peers in the comparison group. Rates of depression were 60% higher and rates of anxiety were 30% higher in the private law cohort. }

- In both groups, incidence of depression and anxiety increased in the seven years between 2011 and 2018 – but the rate of increase was higher in the private law cohort.

- Girls were more likely to experience depression and anxiety than boys. This is in keeping with trends within the comparison group (reflecting the general population).

- Older children were more likely to experience depression and anxiety than younger children (under 10). This also reflects trends in the comparison group.

- Children involved in private law proceedings were also more likely to go on to develop depression or anxiety than children in the comparison group, suggesting that they continue to be at heightened risk of mental health problems after proceedings.

Reflection

Given the higher rates of anxiety and depression for children involved in private law proceedings, careful thought needs to be given to how the system impacts on children already experiencing heightened vulnerability. In particular whether there is a way for the system to act as a gateway to appropriate support in situations where these issues are identified.

References

Acquah, D. Sellers, R. Stock, L. Harold, G. (2017). Interparental conflict and outcomes for children in the contexts of poverty and economic pressure. Early Intervention Foundation,London. https://www.eif.org.uk/report/interparental-conflict-and-outcomes-for-children-in-the-contexts-of-poverty-and-economic-pressure.

Baldwin, H. Biehal, N. Cusworth, L. Wade, J. Allgar, V. Vostanis, P. (2019). Disentangling the effect of out-of-home care on child mental health. Child abuse & neglect, 88, pp. 189–200. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.011.

Bedston, S.J. Pearson, R.J. Jay, M.A. Broadhurst, K., Gilbert, R. Wijlaars, L. (2020). Data Resource: Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) public family law administrative records in England. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(1), pp.1-17. https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1159.

Cafcass/Women’s Aid. (2017). Allegations of domestic abuse in child contact cases. https://www.cafcass.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Allegations-of-domestic-abuse-in-child-contact-cases-2017.pdf.

Cusworth, L. Bedston, S. Trinder, L. Broadhurst, K. Pattinson, R. Johnson, R.D. Alrouh, B. Doebler, S. Akbari, A. Lee, A. Griffiths, L. Ford, D. (2020). Uncovering private family law: Who’s coming to court in Wales? Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, London. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/private-family-law-whos-coming-to-court-wales.

Cusworth, L. Hargreaves, C. Alrouh, B. Broadhurst, K. Johnson, R.D. Griffiths, L.G. Akbari, A. Doebler, S. John, A. (2021). Uncovering private family law: Adult characteristics and vulnerabilities (Wales). Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, London. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/uncovering-private-family-law-adult-characteristics-and-vulnerabilities-wales.

Cusworth, L. Bedston, S. Alrouh, B. Broadhurst, K. Johnson, R.D. Akbari, A.

Griffiths, L.G. (2021). Uncovering private family law: Who’s coming to court in England? Nuffield Family Justice Observatory London. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/private-family-law-whos-coming-to-court-england.

Ford, T. Vostanis, P. Meltzer, H. Goodman, R (2007). Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: comparison with children living in private households. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(4), pp. 319–325.

Ford, D. Jones, K. Verplancke, J.P. Lyons, R. John, G. Brown, G. Brooks, C. Thompson, S. Bodger, O. Couch, T. Leake, K. (2009). The SAIL Databank: building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC health services research, 9(1), p. 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-157.

Griffiths, L.J. Mcgregor, J. Pouliou, T. Johnson, R.D. Broadhurst, K. Cusworth, L. North, L. Ford, D.V. John, A. (2022). Anxiety and depression among children and young people involved in family justice court proceedings: Longitudinal national data linkage study. BJPsych Open, 8(2), E47. doi:10.1192/bjo.2022.6

Grych, J. H. and Fincham, F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), pp. 267–290. https://doiorg/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267.

Harding, M. and Newnham, A. (2015). How do county courts share the care of children between parents? Coventry: University of Warwick.

Harold, G.T. Sellers, R. (2016). What works to enhance interparental relationships and improve outcomes for children? Early Intervention Foundation, London. https://www.eif.org.uk/report/what-works-to-enhance-interparental-relationships-and-improve-outcomes-for-children.

Harold, G. T. and Sellers, R. (2018). Annual Research Review: Interparental conflict and youth psychopathology: an evidence review and practice focused update. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), pp. 374–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCPP.12893.

Hughes, K. Bellis, M.A. Hardcastle, K.A. Sethi, D. Butchart, A. Mikton, C. Jones, L. Dunne, M.P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), pp. e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4.

Hunt, J. and Macleod, A. (2008). Outcomes of applications to court for contact orders after parental separation or divorce. Ministry of Justice, London.

John, A. McGregor, J. Fone, D. Dunstan, F. Cornish, R. Lyons, R.A. Lloyd, K.R. (2016). Case-finding for common mental disorders of anxiety and depression in primary care: an external validation of routinely collected data. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 16, pp. 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0274-7.

Johnson, R. Ford, D.V. Broadhurst, K. Cusworth, L. Jones, K.H. Akbari, A. Bedston, S. Alrouh, B. Doebler, S. Lee, A. Smart, J. Thompson, S. Trinder, L. Griffiths, L. J. (2020). Data Resource: Population level family justice administrative data with opportunities for data linkage. International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1339.

Johnson, R.D. Griffiths, L.J. Hollinghurst, J.P. Akbari, A. Lee, A. Thompson, D.A. Lyons, R.A. Fry, R. (2021). Deriving household composition using population-scale electronic health record data—A reproducible methodology. Edited by Ramagopalan, S.V. PLOS ONE. 16(3), pp. e0248195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248195.

Jones, K.H. Ford, D.V.Thompson, S. Lyons, R. (2019). A Profile of the SAIL Databank on the UK Secure Research Platform. International Journal of Population Data Science, 4(2).

Kerker, B.D. Zhang, J. Nadeem, E. Stein, R. Hurlburt, M.S. Heneghan, A. Landsverk, J. McCue Horwitz, S. (2015). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health, Chronic Medical Conditions, and Development in Young Children. Academic Pediatrics, 15(5), pp. 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.005.

Lyons, R. A. Jones, K.H. John, G. Brooks, C.J. Verplancke, J.P. Ford, D.V. Brown, G. Leake, K. (2009). The SAIL databank: linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 9(1), p. 3. https://doi.org10.1186/1472-6947-9-3.

Ministry of Justice. (2018). Family Court Statistics Quarterly, England and Wales, Annual 2018 including October to December 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-court-statistics-quarterly-october-to-december-2019

National Assembly for Wales: Welsh Parliament, Children, Young People and Education Committee. (2020). Mind over matter : Two years on. https://senedd.wales/SeneddCYPE

Rodgers, S.E. Lyons, R.A. Dsilva, R. Jones, K.H. Brooks, C.J. Ford, D.V. John, G. Verplancke, J.P. (2009). Residential Anonymous Linking Fields (RALFs): a novel information infrastructure to study the interaction between the environment and individuals’ health. Journal of Public Health, 31(4), pp. 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdp041.

Roe, A. (2021). Children’s experience of private law proceedings: six key messages from research. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, London. www.nuffieldfjo.org.

Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform. The Platform. https://adolescentmentalhealth.uk/Platform

Stats Wales. (2014). Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2014 – Summary: Revised. https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Community-Safety-and-Social-Inclusion/Welsh-Index-of-Multiple-Deprivation/Archive/WIMD-2014

-

Lancaster University

Lancaster University -

Swansea University Medical School

Swansea University Medical School -

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research -

Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform

Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform -

Family Justice Data Partnership

Family Justice Data Partnership -

SAIL Databank

SAIL Databank