In July 2022 the President of the Family Division launched the national deprivation of liberty (DoL) court.

Based at the Royal Courts of Justice, it deals with all new applications seeking authorisation to deprive children of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction and will run for a 12-month pilot phase initially. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory was invited to collect and publish data on these applications.

Since July 2022, we have published monthly briefings highlighting high level data trends: July and August, September, October and November.

With six months of data, we can now start to reflect on what we are learning about the use of DoL applications in the beginning phase of the DoL court – including the number of children subject to DoL applications and the variation in use of DoL applications across England and Wales.

About the data

The data reported in this briefing relates to all applications issued by the national deprivation of liberty court. It covers information included on the C66 application form – the form used to apply for an order under the high court inherent jurisdiction in relation to children. Data is extracted and recorded by court staff and analysed by Nuffield Family Justice Observatory.

Data caveats and limitations

Data is extracted on a monthly basis from a live data-recording system and reflects the most accurate information at the time of analysis; however figures are subject to revision. In some instances, data may be missing if it is not recorded on the application form1. Missing data is excluded from analyses.

We report data at the application level. This may mean that if the same child is subject to more than one application, or the local authority makes multiple applications within a case, some children may appear in the data more than once.

Data relating to the number of deprivation of liberty applications is not available from another data source and it is therefore not possible to compare our data to alternative records. Due to potential differences in recording systems, caution should be exercised in comparing data from the national DoL court to data collected via different sources in previous years.

In the monthly data briefings, we are limited in reporting on information recorded in the application form only – this provides an indication of how many applications are being made each month but does not provide detailed information about the children subject to deprivation of liberty applications or the outcome of applications. Alongside this briefing we have published the first detailed report on the needs and characteristics of children subject to deprivation of liberty applications. Read this briefing HERE.

How many applications have there been?

Between July and December 2022, the national DoL court recorded a total of 676 applications.

In some cases, a ‘repeat’ application is issued within the same case – for example, to extend an existing order or to vary the current order (e.g. if the child moves placement or additional restrictions on their liberty are sought). So far, there have been 23 ‘repeat’ applications2.

This means that a total of 657 children have been subject to DoL applications at the national DoL court since 4 July (including a very small number of applications for sibling groups).

On average, there have been 113 applications per month, with the highest number of applications issued in August (131 applications). In the most recent month, December 2022, there were 104 applications.

What does this tell us?

The number of applications to deprive children of their liberty appears to be considerably higher than applications for secure accommodation orders:

- between July and September 2022, 46 applications were made to the family courts to authorise the placement of a child in a secure children’s home, according to data from the Ministry of Justice

- in the same period, there were 348 applications to the national DoL court – more than seven times the number of applications for secure accommodation orders.

This suggests that applications under the inherent jurisdiction now significantly outnumber applications under the statutory scheme for placing children in secure children’s homes.

The number of applications has remained fairly consistent since July, at around 110 per month. If this pattern continues, we could expect to see around 1,300 applications issued by the end of the pilot in June 2023.

National data on DoL applications under the inherent jurisdiction has not been published before. A one-off analysis of Cafcass data by Nuffield FJO found that the number of applications in England increased from 103 in 2017/18 to 579 in 2020/21 – an increase of 462% over three years (Roe 2022). Prior to the launch of the national DoL court, this provided the best estimate of the number of applications per year, although it covers England only. Due to potential differences in the recording of the data, it is difficult to draw exact conclusions about the increase in deprivation of liberty applications in recent years.

Nonetheless, the data emerging from the national DoL court does show that a considerable number of applications have been made in just six months.

There are likely multiple, overlapping reasons for the increase in the use of DoL applications over time. While it is not possible to draw conclusions about this from the data, reasons might include the following.

- Capacity in secure children’s homes does not match demand for places: Since 2002, 16 secure children’s homes have closed (Roe 2022), and there are now significantly more children referred for a place in a secure children’s home than there are places available. According to Ofsted, by 31 March 2022, there was an average of 48 children waiting for a welfare place in a secure children’s home at any one time. These children may instead be being placed in unregulated secure settings under DoL orders.

- Ban on under 16s in unregulated placements: In September 2021, changes in legislation meant that children in care aged under 16 could no longer be accommodated in unregulated independent or semi-independent placements, although the high court subsequently confirmed that the inherent jurisdiction can still be used to authorise the deprivation of liberty of a child under 16 in an unregulated placement [see MBC v AM & Ors (DOL Orders for Children Under 16) [2021] EWHC 2472 (Fam)]. This may have led to an increase in the number of DoL applications from September 2021.

- There is also some evidence that the needs of children referred to secure children’s homes have become more complex, and existing homes are struggling to meet these needs and keep children safe (see Roe 2022 for a review of the evidence). As a result, an increasing number of children are being turned away from registered provision and alternative placements must be sought.

- At the same time, the number of inpatient child mental health beds has fallen by a fifth since 2017, despite rising demand. Children who may have previously been cared for in inpatient mental health settings may instead be being made subject to DoL orders.

- It is also possible that following the judgment handed down by the supreme court in the so-called Cheshire West case in March 2014 – which sought to establish a common threshold to determine when a DoL may arise – local authorities have become more aware of the need to apply for permission to restrict the liberty of children and adults when they previously would have not. Further judgments published in the family court (e.g. Re D (A Child) (2019)) may have continued to increase awareness about when court authorisation should be sought in cases concerning children.

- More broadly, in the last decade there has been a considerable increase in the number of older children and young people coming into care, and some evidence that the care system is struggling to fully meet their needs (for more research on young people in care see our work HERE)

Who is making the applications?

Between July and December 2022, 135 different local authorities and 10 hospital or mental health trusts made applications for DoL orders. Those issued by hospital trusts are usually to authorise restrictions of children’s liberty in hospital when the child may not be in the care of the local authority, or where the local authority is also a party in the case.

Most local authorities in England (82.0%) and Wales (59.1%) have made applications to the DoL court to deprive children of their liberty, indicating widespread use across the country.

How does the number of applications by local authority vary by region?

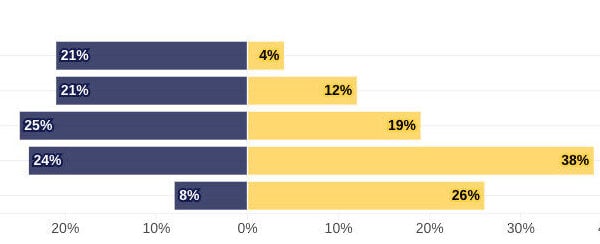

Between July and December 2022, just over a fifth (21.3%) of all applications were made by local authorities in the North West of England, followed by 17.3% of applications from local authorities in London. Local authorities in the North East have made the fewest number of applications (3.8% of the total). This pattern of regional variation has broadly remained the same since July.

What does this tell us?

In order to explore this pattern of regional variation further, we calculated the rate of children subject to DoL applications per 100,000 children aged 10 to 17 in each region of England, and in Wales. This provides an indication of the number of applications made per region while taking into account variations in the size of the population in each area.

The North West had the highest rate of applications, with 19.92 DoL applications per 100,000 children, followed by the South West (14.49 per 100,000), London (13.72 per 100,000), and the East Midlands (12.06 per 100,000). Yorkshire and the Humber and the East of England had the lowest rates, with 7.62 and 8.13 applications per 100,000 children, respectively.

England and Wales had similar rates, of 12.03 and 12.18 DoL applications per 100,000 children respectively, indicating similar use of DoL applications across England and Wales.

Although local authorities in the North West as a whole made the most applications to the national DoL court, the individual local authorities that made the most applications were not all in the North West. The most applications to the national DoL court were made by local authorities in the South West, the East Midlands and the South East3. This suggests that there is considerable variation in the use of DoL applications within regions, with their use varying across individual local authorities in England and Wales.

There are multiple possible explanations for this variation, including variation in the number of children in care, variation in the needs of children and families, and variation in access to and the availability of residential provision, including secure children’s homes, and mental health services. For example, previous analysis found that, between 2011 and 2020, the North East had the highest rate of secure accommodation applications per 100,000 children of all regions in England (11.4 per 100,000 children) (Roe, Cusworth and Alrouh 2022).

There may also be some variation in how areas use DoL applications – previous reports have called for greater clarity on the circumstances that might give rise to a DoL, including what level of care constitutes a restriction of a child’s liberty and in what circumstances parents can consent to restrictions, to help local authorities determine when it is necessary to seek court authorisation for a child’s care arrangements (see for example Parker 2022). It is also important to stress that the data does not necessarily provide a complete picture of the number of children who are deprived of their liberty: the previous Children’s Commissioner for England has raised concern about the number of children who may be illegally deprived of their liberty (i.e. where their care arrangement imposes restrictions on their liberty but court authorisation has not been sought; Waldegrave 2020).

How old are the children?

The majority of children (57.2%) involved in applications were aged 15 and above. The average age of children was 15.

Children referred for places in secure children’s home are also, on average, aged 15 (Roe et al. 2022; Williams et al. 2020).

A small but significant number of applications related to children under 13 (61 children, 9.1%). . It is worth noting that if an application is made to place a child under 13 in secure accommodation then regulations require the approval of the Secretary of State (in England) or Welsh ministers (in Wales) before the child is placed (The Children (Secure Accommodation) Regulations 1991, regulation 4 and The Children (Secure Accommodation) (Wales) Regulations 2015, regulation 13). These additional safeguards do not exist for younger children subject to DoL applications.

Data from the court of protection also shows that a total of 57 16 and 17-year-olds were subject to applications to deprive them of their liberty under the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) (2005). The MCA (2005) applies to children aged 16 and 17, and adults, who lack capacity to make decisions about their care arrangements (for example because of a learning disability). Further research is needed to understand potential differences between older children subject to applications under the inherent jurisdiction of the high court and the court of protection.

What gender are the children?

The number of girls and boys subject to applications is almost equal – a pattern that has broadly remained consistent month-by-month during the first six months of the DoL court.

Again, this is a similar gender profile to children who are referred for places in secure children’s homes in recent years (Roe et al. 2022; Williams et al. 2020).

Further analysis

Our previous monthly briefings:

Our first detailed report on the needs of the children subject to deprivation of liberty applications can be found HERE

1 Nuffield FJO has previously published information on the number of deprivation of liberty applications from Cafcass data. This was a one-off analysis and data from Cafcass is not published regularly.

2 Note that this only includes applications from July 2022, when the national DoL court was launched. It is not possible to identify applications to extend or vary orders that were made prior to the national court, or orders that were originally made in local courts, due to the way the data is recorded.

3 Note we have not published data by local authority due to small numbers and the risk of identification of individual cases and children in doing so.