This summary highlights the main findings from an analysis of the first two months of

applications to the national deprivation of liberty (DoL) court (July and August 2022),

focusing on the orders made in these cases.

The analysis aimed to answer the following research questions:

- What is the legal outcome of applications?

- How long are orders made for?

- Where are children placed while subject to DoL orders?

- What restrictions are being authorised on children’s liberties?

- How is children’s voice and participation in court proceedings being facilitated?

- What role do parents and carers have in proceedings, including access to

legal representation? - What is the process for reviewing orders?

About the data

The data used in this study relates to children who were subject to applications for DoL orders issued to the national DoL court between 4 July and 31 August 2022.

We aimed to follow up the legal orders on the 208 cases included in our first analysis of the needs of the children (Roe and Ryan 2023). Ultimately, we were only able to include 113 of the 208 cases in this analysis. Cases were excluded in circumstances where we did not have information on our data recording system of all the legal orders made in a particular case up to 31 December 2022, including cases that were returned to the local family court at or before first hearing.

We tracked cases throughout the first six months of the court’s operation (up to 31 December 2022). Information relevant to our research questions was extracted from the order(s) made in each case.

In order to check the representativeness of our key findings we also looked at a further 100 orders that were issued (in separate cases) in February 2023 (see Appendix A).

Key findings

- In the majority of the 113 cases (92.0%, 104 cases), the application for a DoL order was granted. In the other 9 cases (8.0%), the application was withdrawn at or before the first hearing. Mainly, this was because a deprivation of liberty was no longer thought necessary but, in some cases, the local authority was directed to apply to the court of protection due to the child’s age, or a secure accommodation order was made to place the child in a secure children’s home.

- Most of the 104 children (68.3%, 71) subject to a DoL order were still subject to an order at 31 December 2022.

- On average, three orders were made in each case, for an average duration of around a month each – but some cases returned to court much more frequently.

- The type of restrictions on children’s liberty authorised by the court were severe. Each child was subject to an average of 6 different types of restrictions, including in almost all cases constant supervision, often by multiple adults (99.0% of cases). The use of restraint was permitted in over two-thirds of cases (69.4%). Restrictions were rarely relaxed over the study period (7 cases, 9.2%).

Restrictions were rarely relaxed over the study period (7 cases, 9.2%). - In over half of cases (53.8%), children were placed in at least one unregistered placement during the study period. When children were placed in unregistered placements, there were considerable delays in providers applying for, or being granted, registration.

- A significant majority of children (over 70%) for whom the deprivation of liberty was sought primarily to manage risks related to criminal exploitation, emotional difficulties, behaviours that were a risk to others, and self-harm, were placed in at least one unregistered placement. Children subject to a DoL order primarily due to a learning and/or physical disability were the least likely to be placed in an unregistered placement (12%).

- The average distance that children were placed away from home while subject to a DoL order was 56.3 miles. This included 6 children who were placed in Scotland (at an average of 254.4 miles from the child’s home area).

- In 17 cases (15.0%) a children’s guardian had not been appointed for the child at first hearing. This was usually due to applications being made at very short notice.

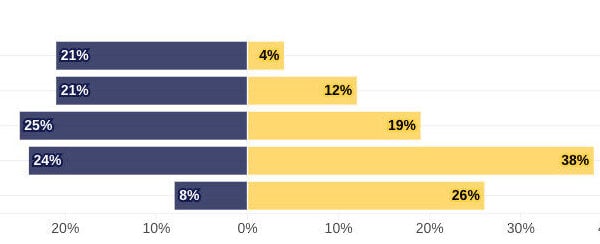

- Children’s opportunity to participate in DoL proceedings was limited. Just 10 (9.6%) children attended at least one hearing in their case, 5 (4.8%) spoke to the judge directly before the hearing, and 6 (5.8%) had written to the judge to share their views. Five (4.8%) children were separately represented (where the child separates from the guardian and instructs their own solicitor in proceedings).

- In just 12 cases (11.5%) parents and/or carers were legally represented for at least one hearing.

Reflections

- Our analysis confirms that children subject to DoL orders are subject to severe restrictions on their liberty and typically remain under such restrictions for significant periods of time. Over a six-month period, only a minority of children experienced a reduction in risk to necessitate an end or a relaxation to deprivations of their liberty. While we have only followed up on cases for six months in this study, this nonetheless calls into question the purpose of DoL orders to facilitate meaningful change in children’s circumstances and long-term outcomes.

- Our findings raise concern about children’s opportunities to formally participate and have their voices heard in DoL proceedings. Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states that children have the right to express their views in all matters affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously. Given the severity of the intervention being considered by the court, and that children subject to DoL applications tend to be teenagers, there needs to be a marked shift in the expectation that children should be given the opportunity to attend hearings or to communicate their views to the court directly. It will require more substantial preparations by the court, children’s guardians and local authorities (or other applicants) to facilitate this.

- Children subject to DoL applications are likely to be placed in unregistered placements, and to be living far from home in often unstable settings. This highlights the urgent need to develop more suitable, local placements for children with complex needs. This should include joint input from children’s social care, mental health services and schools. Given the volume of applications to the national DoL court, this will require significant commitment at local and national level, including national government.

- While information about children’s access to therapeutic care and education provision was limited in the orders, concerns about access to interventions, education and other activities were often raised by the court as well as by children’s guardians and parents or carers. There is a need for further research to explore the quality and type of care that is provided to children subject to DoL orders, in registered and unregistered placements, and including children’s own experiences of DoL orders.

- Unlike in care proceedings, parents are not automatically entitled to legal aid for legal representation in DoL cases. Our report confirms that most parents or carers do not have legal representation. Given the nature of DoL cases, and the severity of intervention in family life being considered by the court, it is hard to understand how this position is justified and there is an urgent need to review it.