In recent years, increasing concern has been raised about the relatively small but rising number of highly vulnerable children who are deprived of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the high court in England and Wales. In spite of the concern, we know very little about the children – their characteristics, behaviours, risk factors or needs.

In July 2022 the President of the Family Division launched a national deprivation of liberty (DoL) court at the Royal Courts of Justice, which is running for a pilot period of 12 months. The pilot was set up partly as a way of managing the listing of the high number of applications coming into local family courts. From July 2022, all applications from England and Wales to deprive children of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the high court were issued at this court.

This report highlights the key findings from an analysis of the first two months

of applications issued by the national DoL court. The research aims to provide a better understanding of who the children subject to DoL applications are, in order to inform conversations at a national and local level about the type of care and provision they need.

The research aimed to respond to the following questions:

- What are the needs, characteristics and circumstances of children subject to DoL applications?

- What are the most common primary reason(s) for a DoL order being sought?

- Are there distinct cohorts of children with different needs, who may require different types of care?

- Who is making the applications, what forms of DoL are they seeking, and where are children being placed?

What is ‘deprivation of liberty’?

The term ‘deprivation of liberty’ comes from Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which provides that everyone, of whatever age, has the right to liberty. A deprivation of liberty (DoL) occurs when restrictions are placed on a child’s liberty beyond what would normally be expected for a child of the same age. This may include them being kept in a locked environment that they are not free to leave, being kept under continuous supervision, and being subject to restraint or medical treatment without consent. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that the restriction of a child’s liberty should be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

For more information, download the full report below.

Deprivation of liberty orders under inherent jurisdiction of the high court

The high court can authorise the deprivation of the child’s liberty under its inherent jurisdiction when none of the other legal mechanisms apply – for example, if there are no beds available in secure children’s homes. It is intended as a last resort measure.

For more information about what constitutes a DoL and the different legal routes for depriving children of their liberty see:

Parker, C. (2022). Deprivation of liberty: Legal reflections and mechanisms. Briefing. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory

Key findings

What are the needs and characteristics of children subject to deprivation of applications?

- Children subject to DoL applications are highly vulnerable. They typically have multiple and complex needs.

- The most commonly identified risk factors were behaviours that were considered a risk to others (e.g. physical or verbal aggression; recorded in 69.2% of all cases), concerns about mental health or emotional difficulties (59.1%), placement breakdown (55.3%), self-harm or suicidal ideation (52.4%) and absconding behaviours (46.6%).

- Most of the children had experienced significant adversities and trauma throughout their childhoods, including abuse and neglect, rejection and bereavement.

- Children were well known to services. Only 10 out of 208 children had recently come to the attention of the local authority and almost all (96.6%) were in care at the time of the DoL application. Just under half (44.7%) had come into care within the last 2 years, with almost a fifth of children (19.2%) coming into care in the 6 months prior to the DoL application being made.

- Children had experienced significant instability in the months and years prior to the application. Several children had experienced periods in and out of care, and over half (55.3%) had experienced multiple changes in their placements.

- 19 children had experienced the breakdown of adoption (10) or special guardianship (9) arrangements, due to the carers being unable to manage the child’s behaviour.

- Most children (70.7%) were aged between 14 and 16 years old at the time of the application but there was nevertheless a significant number of children who were aged 12 and under (7.2%).

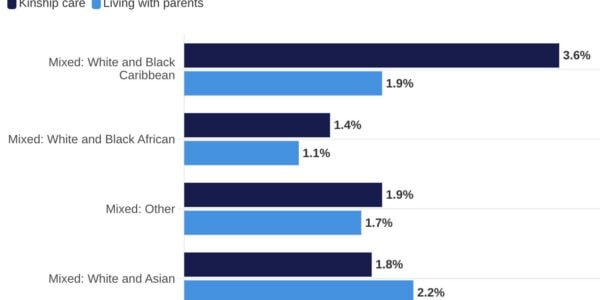

- Information about children’s ethnicity was not consistently recorded but initial analysis suggests an overrepresentation of children from Mixed, Black and White Other ethnic backgrounds among children subject to DoL applications.

What was the main reason for the DoL application?

- In most cases the DoL application was made due to concerns about the child’s behaviours, and the severe and immediate risk of harm faced by the child or others as a result of this.

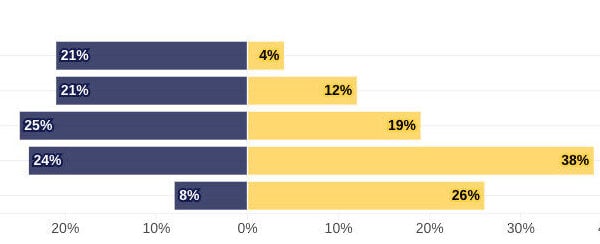

- We identified seven primary reasons that a DoL application might be made, reflecting the main concern in each case. The most common reason was ‘risk to others’ (24.0% of all cases), related to concerns about the risk posed to others from the child’s behaviour, examples of which included violence towards others, and/or causing damage to property either in the placement or the community, including setting fire to things.

- The second most common primary reason for a DoL application, in just over a fifth (22.1%) of cases, was to manage a child’s needs or behaviours that were the result of a severe learning disability, a physical disability and/or autism.

- Other primary reasons included self-harm (16.8% of cases), mental health (12.5%) – identified as a primary reason where there was evidence of a diagnosis of mental health disorder, and/or treatment from specialist mental health services in the past or currently – sexual exploitation (10.6%) and criminal exploitation (8.7%).

- In a small number of cases (5.3%) the reasons given for the DoL did not fit the situations described above. This included cases where the main concern was the use of drugs (including class A drugs) and alcohol by the child, or cases where the main concern was the child going missing for periods of time.

- Although we were able to identify a primary reason for the application – the central concern that led to the DoL application being made – in almost all cases (95.2%), there was more than one risk factor present and most (65.7%) had four or more. The children had multiple and overlapping needs.

- There were notable gender differences in the reason for the DoL application, with girls much more likely to be subject to applications due to self-harm, mental health, and sexual exploitation, while boys were more likely to be subject to applications due to concerns about the risks they posed to others and criminal exploitation. This may reflect gendered differences in the understanding of children’s behaviours – with girls’ challenging behaviours more likely to be seen as relating to internalising difficulties and boys’ with externalising or ‘aggressive’ behaviours – and assumptions about extrafamilial risks faced by girls and boys.

Are there distinct cohorts of children with different needs, who may require different types of care?

We identified three broadly distinct groups of children – for whom the DoL application was being sought for different reasons – which may help guide future service development. In all three groups, there was a high level of need and severe risk of harm that was considered difficult to manage without restrictions on the child’s liberty.

- Children with learning and physical disabilities needing support/supervision: In these cases, the DoL was sought primarily due to a need to monitor and supervise the child to manage their care needs and/or to place restrictions on their liberty to manage challenging behaviours that were linked to the disability.

- Children who had multiple, complex needs, which were often recognised to be a response to complex and ongoing trauma. These were cases where children were considered to be very vulnerable as a result of a range of overlapping risk factors and needs, primarily related to mental health concerns, self-harming behaviours and risk to others.

- Children experiencing or at risk of external or extrafamilial risk factors such as sexual or criminal exploitation. In these cases, the primary concern was to manage the immediate risk of exploitation – although the children in this group also had multiple, complex needs, often as a response to complex and ongoing trauma.

What was being applied for, and by whom?

- In our sample, the majority (97.5%) of DoL applications were made by local authorities. Five applications (2.4%) were from hospital trusts.

- The restrictions on children’s liberty that were requested in the applications were multiple and involved severe constraints on the child, including, in almost all cases, constant daytime supervision (ranging from 1:1 to 4:1 adult to child supervision), as well as the locking of doors and windows to prevent the child leaving the placement, restrictions on their use of the internet, social media and mobile phone, and access to belongings, including money, and the use of physical restraint.

- Too few placements were available that could meet the complex needs of children. In just under half of applications, children were going to be placed in unregistered settings (45.6%) – this included the use of semi-independent (unregulated) placements, hospitals, residential homes that were Care Quality Commission (CQC) but not Ofsted-registered, and rented flats or holiday lets staffed with agency workers.

- We found that children with learning and physical disabilities were less likely to be placed in an unregistered setting. In contrast, where the DoL application was primarily related to concerns around self-harm, risk to others and/or criminal exploitation, children were more likely to be placed in an unregistered setting. This may indicate a particular lack of sufficient and suitable placements for children with these needs.

Reflections

- Our analysis confirms the complexity and severity of risk faced by children subject to DoL applications and highlights an urgent need for increased resource, creativity and collaboration across all systems responsible for the care of these children if we, as a society, are going to better meet their needs.

- Children who are subject to DoL applications are extremely vulnerable. They typically have multiple and complex needs that are evident in behaviours that can make them a risk to themselves or others. Some have severe physical or learning disabilities, some have been subject to criminal or sexual exploitation. Most have experienced significant adversities such as rejection, bereavement, abuse and neglect during their childhoods.

- Although their needs may have recently escalated, the vast majority of children who are subject to DoL applications are well known to statutory services. For many children, their emotional and behavioural difficulties are evident from late childhood. It is clear that they need far better support at an earlier stage.

- By the time they are subject to a DoL application, the risks children face are immediate and severe. It is obvious that they are in need of intensive care: as a minimum, they are likely to require care that is stable, with consistent professional support from carers who are able to build trusting relationships over time, along with access to specialist therapeutic support and education. Yet we know that in many cases this is not available. Applications are too often made to place children in unregistered provision as a stopgap in the hope that more suitable provision will become available. But a dire national shortage of suitable homes means that in many cases, children will remain in temporary or crisis placements for much longer.

Priorities for further research

- What are children’s experiences of being deprived of their liberty, and what opportunities do they have to participate and have their voice heard in proceedings?

- What are the short and longer-term outcomes for children subject to DoL orders?

- What is the ethnicity of children subject to DoL applications and is there any variation in their needs, the reason(s) for the application, and the arrangements made for their care by ethnicity? Information about children’s ethnicity was often not included in application forms.

- What access do children have to education when subject to DoL orders?

- Are staff who are caring for children subject to DoL orders sufficiently trained to provide the level of care required, including with regard to the use of restraint?

- How are orders made under the inherent jurisdiction being reviewed and monitored, and how does this compare to the requirements for monitoring and review under the statutory schemes?

- How many parents are legally represented in DoL cases and what are the barriers to accessing representation? Given that, in our study, the majority of applications for a DoL were made outside of care proceedings, it appears that most parents would not automatically be entitled to legal aid for legal representation.

- What is the impact of parental consent on whether DoL orders are made or not?

This report underlines the urgent need to develop new provision, at a local level, with joint input from children’s social care, mental health services and schools. It is not something that can be left to chance. It will require a nationwide strategy, with significant commitment at local and national level, including national government.

Shane’s story

The stories of children in this study are fictionalised, based on common factors that occurred in multiple cases. This is to avoid identification of children.

Shane is 15. He was removed from his birth parents as a baby and adopted when he was a year old. Concerns about his behaviours started to escalate when he was 8 years old, following an incident that led to him being temporarily excluded from school. His adoptive parents began to struggle with his behaviour and he came into care under s.20 when he was 11. He has had a series of placements in residential care, all of which broke down because the home could not manage his behaviour. He can be verbally and physically aggressive, has assaulted staff, and damages property. He has self-harmed, taken overdoses of medication, and has said he wants to kill himself. He smokes cannabis and drinks alcohol. He was settled for several months in one placement, with a DoL in force, until an incident when he attacked staff and set fire to furniture, at which point the placement gave notice. The local authority has struggled to find a new placement for Shane and is proposing to place him in a rental flat under a DoL order while it continues to search for a registered placement. The restrictions sought are 3:1 supervision, the removal of items that he could use to harm himself, sharp objects and medication locked away, plastic plates and cutlery, monitoring throughout the night, doors and windows locked. He will not be permitted to leave placement, and physical restraint will be used as a last resort.

Claudia’s story

The stories of children in this study are fictionalised, based on common factors that occurred in multiple cases. This is to avoid identification of children.

Claudia is 16 and is currently in hospital following an overdose of painkillers. She has been in hospital for a month and, although she is medically fit for discharge, the local authority cannot find a placement. She was living in a residential placement under s.20 but the placement provider has given notice. In the last 18 months, Claudia has tried to commit suicide on numerous occasions, through cutting herself, overdosing, and walking onto train lines. She regularly goes missing from home and school, and says that she no longer wants to be alive. Her mental health problems escalated with the recent death of a family member. When in hospital she attempts to leave constantly and is abusive to staff. She is continuing to self-harm. She has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and anxiety. She was assessed under the Mental Health Act but did not meet the criteria for a secure bed. The local authority is seeking a DoL order while she remains in hospital and while it continues to search for a placement. This will involve constant 2:1 supervision at all times and permits the use of restraint to prevent her from absconding or self-harming. It is expected that the DoL will continue in a residential placement.

Gary’s story

The stories of children in this study are fictionalised, based on common factors that occurred in multiple cases. This is to avoid identification of children.

Gary is 15, has recently come into care via s.20, and is living in an unregistered

placement away from his home area. He has been known to children’s social care on and off since he was 2, due to concerns about domestic abuse in the family home and his mother’s use of drugs and alcohol. The main concerns relate to criminal exploitation and his involvement in selling drugs. When at home he would go missing on a regular basis for long periods of time. On one occasion he was found some distance from home in a ‘cuckoo house’. At the moment, he is able to leave the placement and frequently returns to his home town. There are concerns that he is continuing to sell drugs there. The local authority is seeking a placement in secure accommodation for him but has so far been unsuccessful. It is seeking a DoL order so Gary can be supervised both in the placement and when he is in the community.

Read more

Since July 2022, we have published monthly briefings highlighting high level data trends from the national deprivation of liberty court: July and August, September, October and November.

With six months of data, we can now start to reflect on what we are learning about the use of DoL applications in the beginning phase of the DoL court – including the number of children subject to DoL applications and the variation in use of DoL applications across England and Wales.

You can read more on what we have learnt from the first six months of data HERE