Introduction

Good data is a vital part of a just and effective family justice system. In any organisation or system, the choices about what is measured reflect priorities; in Lord Darzi’s words, ‘What gets measured, get managed’ (Darzi 2024).

Reliable, meaningful data not only enables people to track progress against aims and objectives but also brings transparency to how the system operates. Data can highlight where things are working – and where improvements are needed – revealing patterns of inequality and areas needing urgent attention.

Without robust data, it is impossible to fully understand the experiences of those who interact with the system or to hold it accountable for delivering fair and equitable outcomes.

The state of family justice data

The National Audit Office has highlighted significant problems with the availability and quality of data in the family justice system (NAO 2025). In 2024, the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) assessed the data in the family justice system through a data mapping exercise. Its report describes the family justice system’s approach to data as fragmented, since there is no single organisation with oversight or ownership of all the data in the system (Ng-Knight, Upadhyay and Papaioannou 2024). NatCen’s assessment revealed critical data gaps (e.g. a lack of pre-court information, limited data on the characteristics of children and their parents, and medium-term outcomes of decisions made in family courts). The report also noted issues with inconsistent data (e.g. domestic abuse is not systematically recorded in family court data, despite its prevalence and importance as a policy issue for the current government).

In response to the NatCen report, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory called for action to improve the data in the family justice system (Saied-Tessier 2024). The report recommended that the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) oversee a data improvement plan or data strategy, introduce stronger data governance, and create a culture of transparency, building on the President of the Family Division’s initiative to improve the transparency of the family justice system.

The NAO has similarly recommended that a data and evidence strategy should be developed by the MoJ, Department for Education (DfE), HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) and Cafcass, working through the Family Justice Board (NAO 2025).

Transparency in family courts

The President of the Family Division led a transparency review in 2019, culminating in a report recommending that family courts should allow accredited journalists and legal bloggers to attend and report on family court cases (President of the Family Division 2021). Subsequently, there was a successful pilot of the recommendations, initially in three areas (Cardiff, Leeds and Carlisle), which was then extended to almost half of the courts in England and Wales. The transparency provisions have applied to all courts in England and Wales since January 2025.

Transparency is about opening up the courts to media coverage – but also having good quality data that can put any media story into some context.

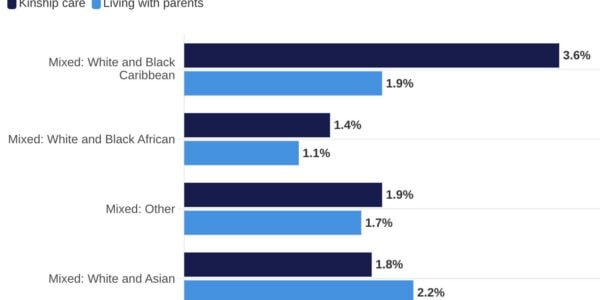

Significant efforts have been made within the family justice system to enhance data quality and availability. Progress has been achieved through ongoing initiatives aimed at improving data. For example, ethnicity data recorded by Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru was, until recently, of insufficient quality to be meaningful, but due to a concerted effort to improve the recording of diversity data, ethnicity data has been used in research and analysis since 2016 (see, for example, Alrouh, Hargreaves et al. 2022). Similarly, the MoJ has adapted its case management system to allow for the recording of deprivation of liberty orders, which it published in July 2023. There has also been investment in Data First, a data-linking research programme funded by ADR UK and led by the MoJ, where accredited researchers can access anonymised Cafcass and HMCTS family court data.

Nevertheless, the family justice system still lags behind other parts of the justice system, and well behind other parts of the public sector, with respect to its data (Saied-Tessier 2024). One of the reasons often cited is the diffuse nature of the family justice system. Lord Norgrove noted in the 2011 Family Justice Review, ‘Family justice does not operate as a coherent, managed system. In fact, in many ways, it is not a system at all’ (MoJ 2011. p. 44). As the NatCen report noted, the family justice system’s approach to collecting and sharing data is fragmented because it is decentralised and relies on information provided by different agencies, including local authorities, Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru (Ng-Knight, Upadhyay and Papaioannou 2024). The system also has a legacy of paper-based records that persisted for longer than other public services (Pope, Freeguard and Metcalfe 2023).

However, change is possible with time, effort and resources. By looking at how other systems have improved their data, it is possible to identify examples where systems have gone from acknowledging data shortcomings to actioning improvements. For example, Lord Darzi’s 2024 Investigation of the National Health Service in England noted that there was almost no centrally held data for mental health until 2016, or for community services until 2021 (Darzi 2024).

The aim of this report is to encourage family justice professionals to learn from good practice and innovation in the youth justice system, to know that challenging new data collection is possible, and can achieve positive outcomes for children and their families.

Comparing data in youth justice and family justice

The youth justice system provides a helpful comparison to the family justice system when examining approaches to data and data availability. Both systems are focused on the welfare of children. Indeed, the needs of children in the youth justice system and the family justice system overlap.

The youth justice system takes a child-first approach. It also provides a helpful comparison to the family justice system because it has explicitly set out its approach to improving data. The Youth Justice Board Strategy 2024–27 articulates that it uses data to ‘identify opportunities to improve and innovate’.

A child-first approach

‘Child-first’ is a principle for the whole youth justice sector, including the approach to collecting data. It means that all youth justice services:

- prioritise the best interests of children, recognising their particular needs, capacities, rights, and potential – all work is child-focused, developmentally informed, acknowledges structural barriers, and meets responsibilities towards children

- promote children’s individual strengths and capacities to develop their pro-social identity for sustainable desistance, leading to safer communities and fewer victims – all work is constructive and future-focused, built on supportive relationships that empower children to fulfil their potential and make positive contributions to society

- encourage children’s active participation, engagement, and wider social inclusion – all work is a meaningful collaboration with children and their carers

promote a childhood removed from the justice system, using pre-emptive prevention, diversion, and minimal intervention – all work minimises criminogenic stigma from contact with the system.

However, although there is value in comparing the two systems, there are differences between them regarding data collecting powers. The Youth Justice Board administers a grant to all youth offending teams and can stipulate data returns as a requirement to receive funding. It therefore has a direct lever to change data collection.

While the grant funding is not present in the family justice system, it has governance structures in place to request changes to data collection. For example, the Family Justice Board includes ministers from the MoJ and the DfE, the chief executives of Cafcass and Cafcass Cymru, as well as senior representatives from local government children’s services. This group has the authority to request changes to data collection.