About

This report summarises what we know about children and young people deprived of their liberty across welfare, youth justice and mental health settings in England and Wales from national administrative data and recent research studies.

Drawing on national administrative data and research from the past 10 years, this report aims to bring together what we know about children deprived of their liberty across welfare, youth justice and mental health settings in England and Wales. It summarises what we know about the number of children held in different settings, who the children are, where they are placed, their experiences of secure care, and what happens to them afterwards.

It follows widespread concern in the child welfare system about a shortage of placements in registered secure children’s homes, the increasing numbers of children being deprived of their liberty in unregistered placements because there is nowhere else for them to go, and the capacity and capability of the system to meet the complex needs of this group of children.

What is a deprivation of liberty?

The term ‘deprivation of liberty’ comes from Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which provides that everyone, of whatever age, has the right to liberty. A deprivation of liberty occurs when restrictions are placed on a child’s liberty beyond what would normally be expected for a child of the same age. This may include them being kept in a locked environment that they are not free to leave, being kept under continuous supervision, and subject to restraint or medical treatment without consent. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that the restriction of a child’s liberty should be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

For more information about what constitutes a deprivation of liberty for children see: Parker, C. (2022). Deprivation of liberty: Legal reflections and mechanisms. Briefing. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/deprivation-of-liberty-legal-reflections-and-mechanisms-briefing

Key messages – what do we know?

How many children are deprived of their liberty?

- The largest group of children deprived of their liberty are living in the youth justice secure estate. The next largest group of children deprived of their liberty are those detained under the Mental Health Act (1983). A smaller number of children are detained in secure children’s homes under section 25 (s.25) of the Children Act 1989. We do not have comparable, up-to-date information about the number of children deprived of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the high court, or under the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- Many more children are referred for a place in a secure children’s home on welfare grounds than can ultimately be placed. In 2020, just one in two children referred for a place in a secure children’s home were found one (National Youth Advocacy Service (NYAS) n.d.).

- There is some evidence that there is a cohort of children with particularly complex needs who are seen as too ‘challenging’ to be suitable for a secure children’s home. This includes children with very complex mental health needs but who do not meet criteria for detention under the Mental Health Act. This has led to a significant increase in the use of the inherent jurisdiction of the high court to deprive children of their liberty in alternative placements. In 2020/21, 579 applications were made under the inherent jurisdiction in England – a 462% increase from 2017/18 (data provided by Cafcass). In 2020/21, for the first time, applications made under the inherent jurisdiction outnumbered applications under s.25 of the Children Act 1989. This is a major cause for concern given that we do not know where these children are placed, what restrictions are placed on their liberty, or what their outcomes are.

- It is not yet clear how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the number of children placed in secure settings and there is need for further research in this area. During this time many secure children’s homes have been operating at reduced capacity, which has placed further strain on the system.

Who are the children?

- A growing body of evidence shows that children entering welfare and youth justice secure settings have a high level of complex needs. This includes experiences of trauma and disadvantage from early childhood, such as exposure to neglect, abuse, family dysfunction, bereavement, abandonment and loss, relationship difficulties, domestic violence and parental problematic substance use, as well as associated experiences of socioeconomic disadvantage, poverty, and discrimination that persist throughout childhood. At the point of being deprived of their liberty children are likely to face multiple difficulties and risks arising from mental health problems, challenging and offending behaviours, problematic substance use, self-harm, educational needs, and risk of sexual and criminal exploitation.

- There are marked similarities in the early life experiences and current circumstances and needs of children deprived of their liberty for welfare and youth justice reasons.

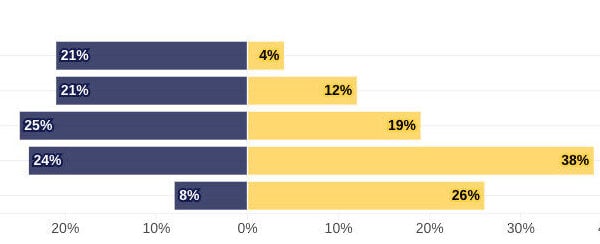

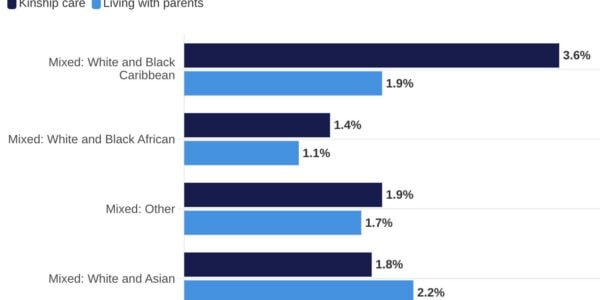

- Children from racialised communities are overrepresented across all types of secure setting.2 This is most stark in the youth justice secure estate, where children of Black, Asian and Mixed ethnic backgrounds make up just over half (51%) of the total population and disproportionality is increasing. Children from Black and Mixed backgrounds are also overrepresented among children referred to secure children’s homes for welfare reasons and those detained under the Mental Health Act. There is some evidence that children from racialised groups receive disproportionate and unequal treatment within secure settings but there is a need for further research to better understand the drivers of this disproportionality and the experiences of children from racialised communities in secure settings.

- We know comparatively little about children detained under the Mental Health Act.

- Although there is a lack of research about children’s experiences prior to entering secure care, a handful of studies have highlighted a lack of early intervention and support in the community for this group. We know that children in welfare placements tend to enter care late, and once in care, experience the repeated breakdown of arrangements made for their care in the community. There is a clear lack of suitable placements, including specialist foster care and residential provision, that can support children with complex needs both before and after a secure placement.

What is secure care?

When children are deprived of their liberty they may be sent to live in one

of several different types of setting, depending on the legal authorisation for

the placement.

• Secure children’s homes accommodate children aged 10–17 placed for welfare reasons, or in youth custody (on remand or serving a custodial sentence).

• Young offender institutions accommodate boys aged 15–17 in youth custody.

• Secure training centres accommodate children aged 12–17 in youth custody.

• Mental health in-patient wards accommodate children of any age detained under the Mental Health Act 1983.1

What is the purpose of secure care?

Although there is a clearer rationale for the detention of children in mental health settings (i.e. to provide treatment for a mental health problem), there is a lack of clarity around the main purpose of depriving a child of their liberty for welfare reasons and in youth custody (i.e. to punish or to rehabilitate), and therefore what an ‘ideal’ system should look like. This includes a lack of clarity around the extent to which these settings should go beyond temporarily keeping children ‘safe’ or ‘punishing’ them, and support children to address underlying needs and promote their resilience and recovery – and what changes to the system may be necessary to achieve this.

Where are children placed?

- The size of the secure estate in England and Wales has declined over the past two decades, in particular with the closure of 16 secure children’s homes since 2002.

- The limited number of secure settings in England and Wales means that children are likely to be living far away from home. In 2019/20, 74% of children in youth custody were placed more than 24 miles from home (Youth Justice Board (YJB) 2021). The median distance from home for children placed in secure children’s homes for welfare reasons was 132.3km (range 0–399km; children placed between 1 October 2016 and 31 March 2018) (Williams et al. 2019). Equivalent data is not available for children detained under the Mental Health Act.

- In addition, over 50 children, on average, have been placed in secure children’s homes in Scotland by English and Welsh local authorities each year over the last five years. From 2022, Scottish secure children’s homes will no longer accept cross-border placements, which will place additional pressure on the availability of welfare secure placements in England and Wales.

- There is a need for further research to explore how distance from home impacts children’s experience of a secure placement and their outcomes, including the experiences of English and Welsh children who are placed in secure children’s homes in Scotland.

- We know very little about where children refused a place in a secure children’s home go on to be placed, including the use of the inherent jurisdiction to deprive them of their liberty in alternative placements.

- The number of children placed in adult in-patient wards while detained under the Mental Health Act is concerning. The most recent data suggests that this practice has increased in the past year (NHS Mental Health Dashboard 2021).

What are children’s experiences of secure care?

- We know more about children’s experiences of youth custody compared to other settings. Serious concerns have been raised about the ability of young offender institutions and secure training centres to keep children safe.

- Children report mixed experiences of living in secure children’s homes and there is a need for further research in this area. For some children, the placement is a positive experience and they benefit from the sense of routine and security the home provides, and positive and nurturing relationships with staff.

- Concern has also been raised about incidents of violence, restraint and self-harm in secure children’s homes. There is evidence of increasing incidents of self-harm among children in these settings, and concern about the ability of secure children’s homes to manage this – including for reasons such as insufficient staff training and resources.

- There is a lack of research about children’s experiences of being detained under the Mental Health Act.

- We know little about the types of intervention and models of care provided in secure settings. The Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS), a whole system trauma-informed therapeutic approach, is currently being developed and evaluated in welfare and youth justice secure settings. This aims to provide more joined-up services, coordinated around a child’s needs.

- There is a lack of research about how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected children’s experiences of living in secure settings, although reports suggest that children in youth justice settings in particular have been subject to further restrictions, including spending significant time in their cells, visiting restrictions and disruption to education.

What do we know about children’s outcomes?

- There is a lack of systematic and longitudinal research about children’s outcomes following secure care. The use of a consistent set of outcome measures – which would follow on from an agreed set of aims/statement of purpose for settings – would help.

- The evidence available does not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn about the impact of a secure placement on children’s short and long-term outcomes.

- We know that reoffending rates for children placed in youth custody are high. There is a lack of data on other outcomes.

- There is very little data on outcomes following detention under the Mental Health Act.

- Some children placed in secure children’s homes on welfare grounds reportedly benefit, but for others the placement is ineffective or makes things worse. In the long term, evidence suggests that a placement in secure care is unable to fundamentally transform children’s outcomes. This is also the result of a lack of coordinated support and suitable placements for children when they leave secure care.

Recommendations for further research

- Information about the number of children deprived of their liberty in different settings and via different legislative routes is collected and published by different government bodies, with varying levels of detail (see Appendix A for an overview). Greater alignment of these datasets would enable a better understanding about the number of children placed in different settings, their characteristics, experiences, and outcomes. For each setting and each legislative pathway, data should include about:

- the number of children deprived of their liberty each month, and the total number each year

- where children are placed, including placement type and distance from home

- demographic characteristics including ethnicity, gender, age and disability

- children’s needs at the point of admission (including information about mental health problems, physical health needs, problematic substance use, previous offences, behaviours, special educational and disabilities needs, school attendance and exclusion, family contexts, previous placements and children’s services involvement)

- behaviour management, including use of restraint and separation, and incidents of self-harm and assault in each setting

- standardised outcomes measures (e.g. mental health, education, relationships, well-being)

- children’s own views about their care.

- Regularly updated, publicly available data about the number of children deprived of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the high court (held by Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and Department for Education (DfE)), the Mental Capacity Act (MoJ) and the Mental Health Act in Wales (NHS Wales) is not available. Given the significant increase in the use of the inherent jurisdiction, this data should be published regularly by MoJ and DfE, including information about the outcomes of applications, the children involved (number and demographics), and where they are placed.

- There is a need for further research about the barriers local authorities experience securing a place in a secure children’s home, including whether children with a specific set of more challenging needs are less likely to be found a place, and where they go onto be placed. Some of this information could be recorded and published by the Secure Welfare Coordination Unit (SWCU), for example success rates and children’s needs, and through linking SWCU data, Cafcass data and DfE’s ‘children looked after’ returns.

- There is an absence of research about the characteristics, needs and early life experiences of children detained under the Mental Health Act – and any similarities or differences with children detained via different pathways – as well as their experiences of in-patient treatment.

- There is a need for more research exploring children’s experiences of secure settings, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Given the overrepresentation of children from racialised communities in secure settings, all research should seek to consider differences in children’s journeys, experiences and outcomes according to their ethnicity and other intersections of identity (e.g. gender and disability), and the drivers of this disproportionality.

- There is a need for more research exploring children’s journeys before and after secure care, including the type and length of placements, involvement with services, and access to support or care in the community, including health and mental health services.

- There is a need for more research on short and long-term outcomes for children placed in all settings, including outcomes relating to mental health, well-being, education, training, health, relationships, contact with services and any further deprivations of liberty. This could be achieved in part by linking administrative data held by different government departments and tracking children’s journeys over time.

- There is little research exploring the factors associated with positive outcomes in secure settings, including comparison with international systems and alternative types of non-secure provision.

Reflections

There is a growing body of evidence that points to the complex needs of children in secure settings, and the similarities between children placed in different settings – particularly among those in youth custody and welfare placements. We know that children placed in secure care are likely to have experienced significant adversity in early childhood, including neglect and abuse, loss, instability, poverty and deprivation, and relationship breakdown – and the resulting complex trauma is highly likely to affect behaviours and vulnerability to risk that may lead to a child being placed in a secure setting. At the point of admission, children have a range of complex and overlapping needs and there is high prevalence of mental health problems, self-harm, problematic substance use, risk of sexual and criminal exploitation, challenging behaviours and educational needs.

At the same time, it is clear that the secure estate in England and Wales is struggling to adequately meet children’s needs.

- There is a lack of early intervention to support children and their families before risk escalates, and once this occurs, a lack of suitable placements and support in the community that might prevent children needing to enter secure settings.

- There is a lack of clarity about the purpose of secure care for welfare and youth justice purposes – the current model is based on either punishment or risk reduction rather than fundamental input to support children’s recovery and reduce risks in the community.

- Demand for welfare placements in secure children’s homes, and the increasingly complex needs of children who are referred, exceeds capacity and capability within the system. Although there is a need for more research in this area, there is evidence of a growing group of children whose needs are too ‘complex’ to be met by the current system. Applications to use the inherent jurisdiction to place children in unregulated secure settings have substantially increased, and in 2020/21, even outnumbered applications under s.25 of the Children Act.

- There is a group of children with very severe mental health needs that do not meet criteria for in-patient mental health treatment. These children are often passed around different agencies with a lack of coordinated care planning between children’s services and mental health services.

- There are widespread concerns about the safety of children in youth custody.

- Although there is a lack of evidence about children’s outcomes, research to date suggests that while some children may benefit in the short term, in the long term a placement in secure care is unable to fundamentally improve children’s outcomes. This is also the result of a lack of coordinated support and suitable placements for children when they leave secure care.

There is a therefore a need to rethink how we meet the needs of this group of children, based on a better understanding of their journeys, strengths and needs, what a ‘positive outcome’ would look like, and the type of trauma-informed, therapeutic and integrated care that would support children’s resilience and recovery both in secure settings and in the community before, after or instead of a placement in secure care. There are some positive examples of models that aim to do this, including: the Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS) currently being implemented across the youth justice secure estate; multi-treatment foster care, which places children at risk of offending with specially trained foster carers, supported by a multi-disciplinary team and ongoing family engagement; and models of therapeutic residential care, such as the Mulberry Bush School in Oxfordshire and Windmill Farm – a residential home that has been jointly commissioned by local children’s services and child and adolescent mental health services in Wales. Building on what we know about children living in secure settings will enable the beginnings of a system that is better able to meet their needs.

References

National Youth Advocacy Service (NYAS). (n.d.). (2021). Secure children’s homes for welfare. 141 miles from home. https://www.nyas.net/141-miles-from-home-challenges-for-children-in-secure-homes/

NHS Mental Health Dashboard. (2021). Data and statistics. Retrieved on 1 November 2021 from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-mental-health-dashboard

Parker, C. (2022). Deprivation of liberty: Legal reflections and mechanisms.Briefing. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/deprivation-of-liberty-legal-reflections-and-mechanisms-briefing

Williams, A., Bayfield, H. Elliott, M., Lyttleton-Smith, J., Evans, R., Young, H. and Long, S. (2019). The experiences and outcomes of children and young people from Wales receiving secure accommodation orders. Social Care Wales. https://socialcare.wales/cms_assets/file-uploads/The-experiences-and-outcomes-of-children-and-young-people-from-Wales-receiving-Secure-Accommodation-Orders.pdf

Youth Justice Board (YJB). (2021). Youth Justice annual statistics. G OV.UK. Retrieved 4 November 2021 from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/youth-justice-statistics#youth-justice-annual-statistics