This blog explores December’s Chart of the Month which looks at the age distribution in public law cases in the family justice system and the age distribution of children in care.

Last month, I took part in my first Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO) practice week. During the time observing and speaking with judges, public law family law solicitors and those assessing families in family residential centres, I was struck by how much of the discussion was about newborn babies and very young children. This stands in stark contrast to my years of research and experience in children’s social care, where attention focuses on older children and the challenges of finding nurturing accommodation and care for those in their teen years (Two recent articles include: Shocking number of children in care live without support of an adult – Big Issue, The criminalisation of children in care | Children’s Commissioner for England). From this reflection, we decided to look at the differences in age distribution in England and Wales. The differences are stark.

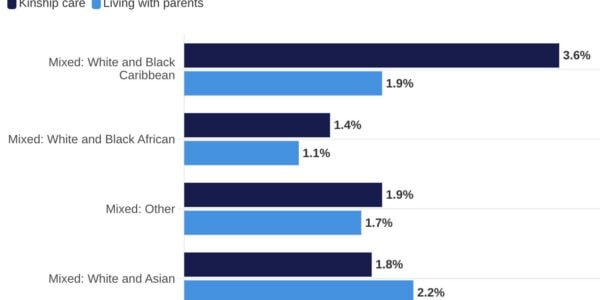

In England and Wales, the majority of public law proceedings in the family courts are for younger children, in contrast to the population of children in care, where most are over the age of 10.

These differences can be partially explained by the fact that a high proportion of cases involving children under a year old will result in adoption or a special guardianship order.

There has also been an increase in older children in care, particularly those on voluntary or consent-based arrangements, who have not come through the family justice system (section 20 of the Children Act 1989 in England and section 76 of the Social Services and Well-being Act 2014 in Wales).

Although children in care are often going through – or have gone through – the family justice system, we don’t systematically map the patterns of overlap. Decisions for care orders may be made with the plan for children to remain in care long-term. Some children remain or return to birth parents; if returned to parents after a period of care, most children remain there, but one in three re-enter care within six years (Reunification and Re-entry to Care: An Analysis of the National Datasets for Children Looked after in England | The British Journal of Social Work | Oxford Academic). Recent research has highlighted that although adoption and special guardianship provide permanency for a vast majority of children, some of these children do re-enter care, most often in the teenage years. After a period of 8 years after the court order, 2% of adoptions and 10% of special guardianship orders disrupted (Family Routes: children who returned to care after leaving for adoption or to live with a special guardian). Questions remain about how to support all permanency options – including children remaining in foster or residential care.

Additionally, the questions for professionals and needs of families may differ when engaging with courts or children’s social care. Children may be at different developmental stages. Family law judges, solicitors and court guardians may be more frequently facing questions on caregiver assessments and permanency orders for very young children. They may be asking questions like: Are parents able to reflect on the child’s experience? Has family support been provided before and during proceedings? What are the quality of caregiver assessments? How has the voice of babies and young children been gathered? Have options been considered? What are the long-term implications of different decisions?

In contrast, social workers in children’s social care may have more focus on accommodation and care for teenagers. They may ask questions like: What’s the child’s wishes and feelings? Where are friendships and relationships that will help this child to grow and develop? Where do they want to live and what are risks in homes and contextual safeguarding risks in the community? If they are going through the courts, they may be asking: What have they communicated to their guardian and have they met with the judge?

Policy and practice — especially support provided before, during and after court proceedings — should be mindful of these differences and understand how decisions in public family law and in children’s social care interact. In my time observing practice, I saw empathetic, thoughtful practice, looking at immediate questions. Judges and solicitors spoke with me about their frustration at the lack of resources to support families after proceedings. Social workers and support workers demonstrated important relational practice to build relationships within statutory and voluntary boundaries. Previous Nuffield FJO work has highlighted challenges for parents with recurrent care proceedings and challenges with deprivation of liberty orders that keep a child immediately safe but don’t help them grow and develop. It has also highlighted innovative models that help answer immediate questions and long-term questions through working towards a new ecosystem (Caring for children in complex situations: Towards a new ecosystem – Nuffield Family Justice Observatory). In my experience of practice week, no matter their role – judge, solicitor, social worker or parent – or the age of the child, the emphasis was on the child.