Today, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) released the latest figures on the number of children subject to applications to deprive them of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court, through their Family Court Statistics Quarterly release.

Quarterly data from July-September 2025 shows that 381 children were subject to deprivation of liberty applications, which authorise the deprivation of a child’s liberty in place other than a secure children’s home. This is the highest quarterly figure since the MoJ began collecting data in July 2023; a 7% increase on the 357 applications for the previous quarter (April-June, 2025) and is slightly higher than the 370 applications for the equivalent quarter last year (July-Sept, 2024).

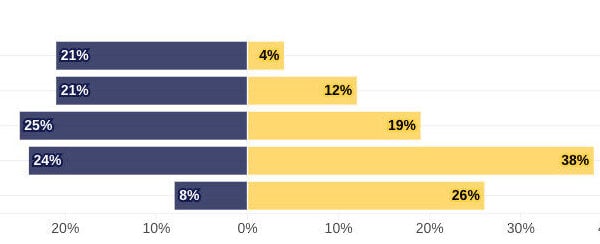

86% of applications were for children over the age of 13, however, there has been a sharp increase in applications for younger children (0-12), which has seen a 52% increase from 33 in April to June 2025 to 50 this quarter.

Patterns of gender remain similar to previous quarters; there were slightly more girls (51%) than boys (48%) subject to deprivation of liberty applications.

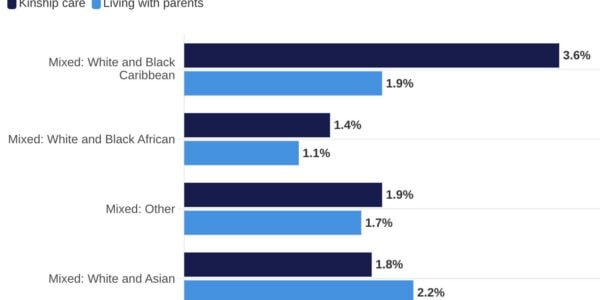

The data this quarter reflects the continuing and extensive use of deprivation of liberty orders, which began to be tracked by the MoJ two years ago. This data is critical to shed light on the persistent use of deprivation of liberty orders within the family justice system, but it is limited in what it can tell us about the children who are deprived of their liberty. The MoJ data release does not tell us why the application was made, the ethnicity of children subject to applications or additional needs they may face.

What are Deprivation of Liberty orders?

Deprivation of liberty orders authorise the deprivation of children in what are often unsuitable, unregulated settings, used to keep them safe in the absence of other options (such as a secure children’s home) and are usually driven by short-term crisis planning. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO) research has highlighted how children on deprivation of liberty orders may have intersecting needs related to mental health concerns, self-harm, having a disability and or experiences of criminal and sexual exploitation. Many of these children will have long and traumatic histories and involvement with services; however, it is often the combined impact of these multiple and intersecting needs – rather than the impact or ‘severity’ of any individual risk factor – that increases a child’s vulnerability.

What does this release of data show?

How many applications were made?

Between July and September 2025, there were 381 applications in the High Court, relating to 381 children. So far in 2025, there have been 1,059 deprivation of liberty applications, which is higher than the 959 applications at this time last year. Research by the Nuffield FJO has highlighted the increasing use of deprivation of liberty orders over the past seven years. Data from Cafcass showed that in 2017/18, there were around 100 applications. In 2024, 1,280 children were subject to applications to deprive them of their liberty, a seven-fold increase.1

This quarter, we have seen some changes in the ages of children subject to deprivation of liberty applications. Between July and September, 50 children between the ages of 0 and 12 were subject to applications, an increase of 52% from the previous quarter (33 children), and a 16% increase from the equivalent quarter last year (43 children). The proportion of children aged 13-15 has also increased (now 60%), and there has been a decline in those aged 16-18, who now make up 24% of deprivation of liberty applications, in comparison to 34% last quarter.

It is concerning to see the rise in younger children subject to deprivation of liberty applications. A child under the age of 13 cannot be deprived of their liberty under a Secure Accommodation Order (s25 of the 1989 Children Act) without authorisation of the Secretary of State for Education. The same is not true of children on a Deprivation of Liberty order issued under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court.

Under measures proposed in the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill, which is currently going through Parliament, the government is proposing to introduce a new legal route to deprive children of their liberty. This is expected to require the Secretary of State’s authorisation for cases involving children under the age of 13.

How does this compare to applications for secure accommodation orders?

It is still the case that deprivation of liberty orders vastly outnumber applications to place children in registered secure accommodation. There is a severe shortage of secure children’s homes. Only 68 applications were made between July-September 2025 for secure accommodation orders, in comparison to 381 deprivation of liberty applications.

What are the next steps for DoLs?

Towards a new ecosystem of care

For over a year, members of a peer collaborative convened by Nuffield Family Justice Observatory shared insights about how children in complex situations are cared for in their regions – Caring for children in complex situations: Five learning points and a case for change and Caring for children in complex situations: Towards a new ecosystem. This provides insights for leaders in social care, health, youth justice, family justice, police and education services who know that change is needed, and who recognise that everyone involved needs to be around the same table to reimagine a better way of working.

The increased reliance on deprivation of liberty orders has come about because services are struggling to work in an integrated way and provide early, timely support to children and families. Key learning includes:

- There is a lack of appropriate accommodation, and the workforce is not equipped to provide high quality, trauma informed care.

- Children rarely present with a single ‘problem’ – but their cases are often managed by single agencies, or several agencies working as separate entities. Services are fragmented and, as a result, professionals rarely have the full story or detailed understanding of a child’s individual needs or circumstances.

- It becomes unclear who has overall responsibility – and children risk falling between the gaps or being placed on pathways managed by single agencies that fail to meet their multiple, overlapping needs.

- Disputes between agencies about a child’s care are not uncommon, and there is a system wide focus on managing risk at the expense of children’s other needs. Little attention is paid to the long-term, damaging consequences of subjecting children to restraint and living in isolation for long periods of time, or to the unsustainable costs of this approach.

Ongoing policy and practice discussions, convened by Nuffield FJO and other partners, continue to explore better and more collaborative ways for professionals across child and adolescent mental health, children’s services, education and youth justice to deliver integrated and timely care for children, preventing more children from being deprived of their liberty.

There is an urgent need to reset services for children who are experiencing the greatest vulnerabilities in our society. A new ecosystem of care would put children’s long-term well-being at the centre, with children and their families listened to and involved in decisions. It would mean health, children’s social care, police and education working together to better support them. Children deserve care from professionals who have a full understanding of their needs and circumstances, who can help them to access the treatment and support they need. Professionals are looking for a clear signal that the government actively supports integrated cross-sector working, and that services can and should be working in this way.Lisa Harker, Director, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory

For further information about the needs and characteristics of children subject to DoLs applications, read our research here.

To receive our bulletin about improving care for children experiencing and living in complex circumstances sign up here.