New analysis of deprivation of liberty orders confirms many children are facing long and severe restrictions in unregistered placements far from home

New analysis of the legal outcomes of deprivation of liberty applications in England and Wales has exposed that it is the norm for children involved in these cases to face severe restrictions, typically for significant periods of time, and to often be placed in unregistered settings far from home – confirming longstanding concerns about children’s experiences.

The research, carried out by Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO), analysed applications received during the first two months of the national deprivation of liberty (DoL) court pilot1 (July and August 2022), focusing on the legal orders subsequently made, with cases tracked for up to 31 December 2022. Nuffield FJO is also regularly collecting, analysing and publishing data from the court, and estimates that approximately 1,300 applications will have been made over a 12-month period.

Nuffield FJO’s study is the first national overview of the outcome of DoL applications. It analysed whether orders applied for are granted and how long for, the nature of the restrictions authorised, where children are placed, and children’s and parent/carers’ participation in proceedings. The study focused on 113 children – a subsection of a larger sample of 208 children included in previous Nuffield FJO research on the needs of children subject to DoL applications.

In 104 of the 113 cases (92 per cent), applications for DoL orders were granted. While these orders are intended to be a temporary measure, most children (68.3 per cent) were still subject to an order on 31 December 2022.

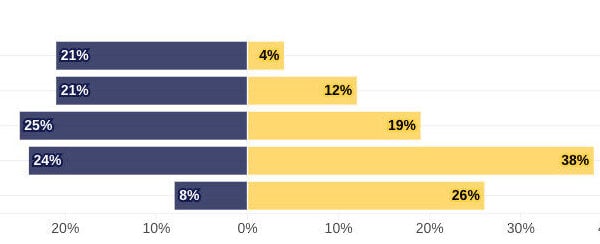

The restrictions authorised by the court involved severe constraints that remained in place for significant periods of time. Each child was subject to an average of six different types of restriction on their liberty, including, in almost all cases (99 per cent), constant supervision, usually by multiple adults. The use of restraint was permitted in over two-thirds (69.4 per cent) of the 104 cases. Over a six-month period, only a minority of children (seven, 9.2 per cent) experienced a relaxation to deprivations of their liberty.

While it didn’t appear that the restrictions applied for were routinely questioned or scrutinised, in some cases, the court ordered the local authority to file an ‘exit plan’, with clear information about how and when the restrictions would be reduced, to share with the child. In a small number of cases, the court refused to authorise some of the restrictions – usually related to the use of restraint or limits placed on the child’s access to the community.

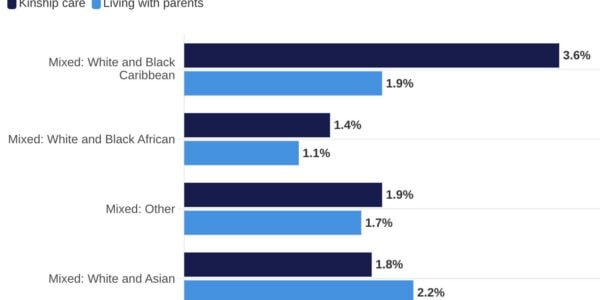

In over half of the cases (53.8 per cent), children were placed in at least one unregistered2 setting, ranging from semi-independent accommodation, Care Quality Commission-registered accommodation, hospital wards, and temporary rented accommodation, including hotels or caravans. A significant majority of children (over 70 per cent) where the deprivation of liberty was sought primarily to manage risks related to criminal exploitation, emotional difficulties, behaviours that were a risk to others, and self-harm were placed in at least one unregistered setting, indicating a lack of suitable regulated provision for children experiencing such risks. Children subject to a DoL order primarily due to a learning and/or physical disability were the least likely to be placed in unregistered accommodation.

The placements were also far away from where children were living – on average 56.3 miles away from their home. Six children were placed in Scotland (at an average of 254.4 miles from the child’s home area).

Information about children’s access to education and therapeutic services was limited in the orders, and concerns about this were often raised by the court, children’s guardians and parents or carers. In several cases, the court directed the local authority to provide a more detailed care plan.

The research also highlights that children have limited opportunities to formally participate and have their voices heard in DoL proceedings. Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states that children have the right to express their views in all matters affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously. Yet just 10 out of 104 children attended at least one hearing in their case. Five spoke to the judge directly before the hearing and six wrote to the judge to share their views. Furthermore, in 15 per cent of cases, a children’s Cafcass guardian had not been appointed for the child at the first hearing. This was usually due to applications being made at very short notice or delays in making children party to proceedings. Five children were separately represented (where the child separates from the guardian and instructs their own solicitor).

Furthermore, despite DoL orders having a severe impact on family life, most parents or carers did not have legal representation; parents and/or carers were legally represented (for at least one hearing) in just 12 cases (11.5 per cent). This is likely to be because parents are not automatically entitled to legal aid for legal representation in DoL cases, unlike in care proceedings.

Lisa Harker, director at Nuffield FJO, said: “The findings of this study confirm that concerns about deprivation of liberty orders – including that many highly vulnerable children are being placed far away from home in unsuitable, unregistered accommodation, with their movements and contact with friends and family being severely restricted – are the norm and not an exception.

“We saw no evidence that these are temporary fixes; children are living in circumstances that are likely to exacerbate their trauma because there is nowhere else for them to go.

“The data from the national DoL court we have been regularly collecting and publishing has been crucial in demonstrating the scale of applications being made – but deeper analysis has allowed us to substantiate anecdotal evidence about children’s experiences. Action is desperately needed to develop local placements with care that can meet children’s needs and ensure meaningful change to their circumstances and health and wellbeing. Critically, the support offered to children and their parents during court proceedings also needs to be improved. It is essential that there continues to be monitoring of this situation. We are pleased that HMCTS has confirmed it will start to collect and publish data about deprivation of liberty cases from July and we are committed to supporting this process.”

The research report on legal outcomes of cases at the DoL court can be downloaded here. Nuffield FJO’s data trends briefing for applications to the court in May 2023 can be found here.

Notes

1 Based at the Royal Courts of Justice, the national DoL court was launched in July 2022 as a 12-month pilot to deal with all new applications to deprive children of their liberty when there are concerns about their welfare via the inherent jurisdiction of the high court. An application can be made to deprive a child of their liberty via the inherent jurisdiction if a local authority has concerns about risks to their safety, or that of others, and no other suitable place – such as in a secure children’s home, or provision under the Mental Health Act – is available. Intended as a ‘last resort’ measure, in England there was a 462 per cent increase in deprivation of liberty (DoL) applications under the inherent jurisdiction between 2017/18 and 2020/21.

2 If a child is living in a setting that is not registered with Ofsted in England or Care Inspectorate Wales – and is being provided with care – it is an ‘unregistered’ placement. This is illegal. ‘Unregulated’ accommodation (including semi-independent or independent placements) is allowed in law for children aged 16 and 17. An unregulated placement becomes unregistered (and illegal) if the child placed there is under 16 years old or if they are under 18 and being provided with care. If the child is subject to restrictions on their liberty (such as being under constant supervision or not being free to leave the placement) that will be regarded as care.