Introduction

Over recent years concern has been raised about the increasing number of children in England and Wales for whom a placement in a secure children’s home is sought but cannot be found. As a result, a number of children from England and Wales are placed in secure care in Scotland instead. The report by the Children and Young People’s Centre for Justice (CYCJ) sets out to help provide a better understanding of the profile and experiences of children placed in Scottish secure care centres by English and Welsh local authorties. It aims to provide an overview of:

- the children’s characteristics – age, gender and ethnicity

- why they were admitted to secure accommodation

- the prevalence and types of adversity they had faced since they were born and in the year prior to admission

- the support and services they had received in the year prior to admission

- their social care histories.

About the data

In 2018 and 2019, CYCJ undertook a census of every child residing in secure care in Scotland on a set day with the aim of understanding their characteristics, risk factors and life experiences. Findings relating to these children were published in: ACEs, Places and Status: Results from the 2018 Scottish Secure Care Census (Gibson 2020); and ACEs, Distance and Sources of Resilience (Gibson 2021).

The current study focuses on 59 of the 165 children – 32 in 2018 (37% of the 2018 sample) and 27 in 2019 (37% of the 2019 sample) – who had been placed in the five secure centres in Scotland by local authorities in England and Wales.

As the sample size is relatively small, and as data was gathered through the gateway of staff completing an online survey rather than interviews with children, caution must be exercised in the interpretation of data.

Key concepts

What is secure accomodation?

Children from England and Wales can be placed in a secure children’s home under section 25 of the Children Act 1989 and section 119 of the Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014. Secure children’s homes are specialist residential homes that are authorised to restrict children’s liberty.

The acts set out the ‘welfare’ criteria that must be met before a child can be placed in secure accommodation:

- the child has a history of absconding and is likely to abscond from any other description of accommodation

- the child is likely to suffer significant harm if they abscond

- the child is likely to injure themselves or others if they are kept in any other type of accommodation.

Section 10 of the Children and Social Work Act 2017 authorises local authorities in England and Wales to place children in secure accommodation in Scotland.

Secure accomodation in Scotland

There are 5 secure care centres in Scotland that accommodate 84 children at any one time, with an additional 6 emergency placements available. Children can be placed in secure accommodation for welfare or youth justice reasons.

Secure care in Scotland is provided by four independent charities and one local authority.

Key findings

- The majority of the 59 children (64%) in secure homes in Scotland who had been placed there by English and Welsh local authorities were aged 15 years or older – this is similar to the proportion of children in this age bracket in secure homes in England and Wales.

- 66% (39) of the children in the cohort were girls, 32% (19) were boys and 2% (1) were transgender.

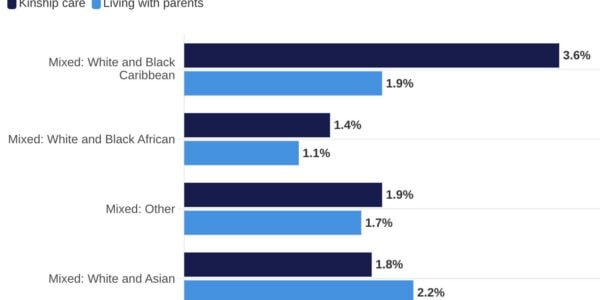

- The majority of the children (75%, 44) were White British – however, children of mixed and multiple ethnicities, and Black, African, Caribbean or Black British children were overrepresented in the cohort compared to the general population.1 In the study, 17% of children were of mixed ethnicity, compared to 5% of children in the general population; and 7% of children in the study were Black, African, Caribbean or Black British compared to 5% in the general population. This ethnicity profile reflects the overrepresentation of children from these groups who are referred for a place in secure children’s homes in England and Wales (Roe 2022).

- The three most commonly cited primary reason(s) for admission to the secure unit were the children’s risk to themselves (53%), absconding (49%), and risk to others (34%). Other reasons included child sexual exploitation (23%) and self-harm (21%).

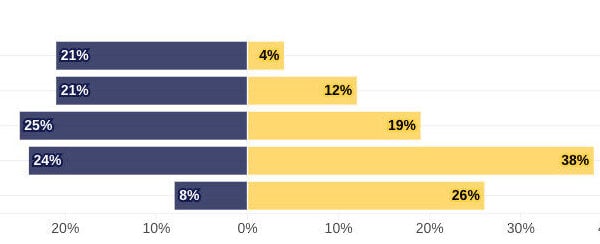

- The children placed in Scottish secure care by English and Welsh local authorities came from familes experiencing relative poverty and living in the most deprived areas of the country.

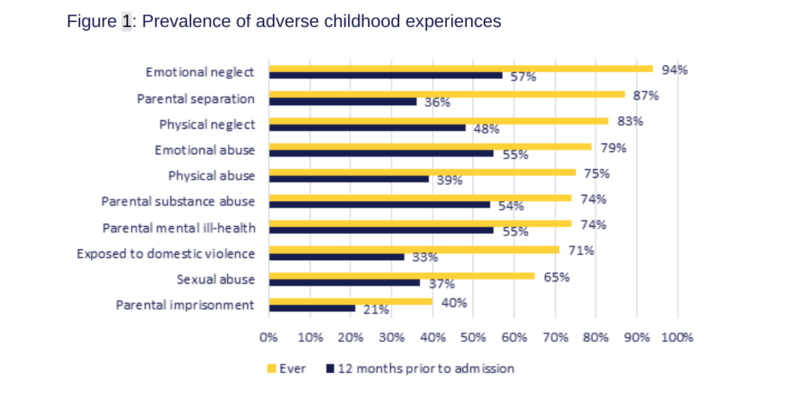

- Children’s experiences of a range of adverse childhood experiences, from birth and in the year prior to admission to secure care, was striking.2 Over 70% had experienced emotional neglect, parental separation, physical neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse, parental mental ill-health, parental substance abuse or exposure to domestic violence at some point in their lives. Exposure to each of the adverse childhood experiences in the last 12 months surpasses what some research would expect to find through the entirety of someone’s childhood (Bellis et al. 2014, 2015; Ford et al. 2019).

– The children had experienced an average of 5.8 adverse childhood experiences and 77% of children had experienced 4 or more of these experiences.

– Children in this study had experienced more adverse childhood experiences than children in a comparable study who were living in a secure children’s home in England (Martin et al. 2021), suggesting that the most vulnerable children are being sent to Scotland. - This cohort are not children who experienced significant difficulties in their earliest years and then achieved a far more stable environment some years later. Rather, the data suggests that they are children for whom intra-familial abuse and risk feature regularly. Their situation in secure accommodation is likely to have been caused by the incremental and persistent effects of year-on-year exposure to adversity and risk.

- Children had also experienced a range of other adversities and risks including mental ill-health, emotional difficulties, substance misuse problems, violence to parents and staff, school exclusion, youth justice involvement and sexual exploitation. Again, the high prevalence of these experiences in the year prior to children being admitted to the secure unit was particularly striking.

- One third of the children were known to social services before the age of 3; 17% were known from, or before, birth.3 Just under a third came to the attention of social work aged 4 to 11, and 34% when aged 12 to 15. Despite the involvement of children’s services in their lives, it was notable that children’s exposure to risks and adverse childhood experiences persisted.

- Prior to entering secure care, children had experienced significant instability in arrangements made for their care, including multiple placement breakdowns and placement moves. In the year prior to admission, 95% of children had experienced a placement breakdown, with an average of 2.8 placement moves during that period

- Almost half (45%) had moved at least 6 times and over a quarter (26%) had moved more than 10 times since birth. One child had experienced 36 different placements.

- Prior to admission into secure care, the majority of children (71%) were living in a residential home.

- A quarter (25%) of the children had had a previous placement in a secure children’s home.

- Our study found that children from local authorities in England and Wales residing in secure care in Scotland in 2018 and 2019 were an average of 353 miles away from their homes. This is considerably further than the average 141 mile distance (from previous placement) of children in secure care in England and Wales reported by Downie and Twomey 2021.

Data gaps and limitations

The study draws on data gathered by CYCJ as part of a census of children in Scotland’s five secure accommodation centres in Scotland in 2018 and 2019. Findings relating to all 165 children concerned were published in: ACEs, Places and Status: Results from the 2018 Scottish Secure Care Census (Gibson 2020); and ACEs, Distance and Sources of Resilience (Gibson 2021). The current study focuses on 59 children who had been placed there by a local authority in England and Wales.

- The data presented in the report is descriptive rather than definitive, providing a snapshot of aspects of children’s lives at two distinct points in time. It may not be consistent with life experiences of children across a longer period of time. Caution must be exercised in the interpretation of data given the relatively small sample size. In instances where the answer to a particular query was not known, the data relating to that question was omitted from the analysis. As such, responses were not always available for all 59 children.

- Data was gathered through the gateway of secure centre staff rather than through direct interviews with the children. The data is thus reliant upon the information, perspective and opinion of those completing the census, and their knowledge of the child in question. While a briefing and guide was provided to each secure care centre in order to assist in their recording, and to achieve a greater degree of consistency, subjectivity will play a role in their submissions. In addition, data relating to adversity is likely to underestimate the form and extent of abuse experienced given likely issues around disclosure.

- Information regarding the frequency of each behaviour was not recorded, meaning that a single episode of harm would be recorded in a similar manner to a pattern. This study is therefore unable to fully describe a pattern of escalating concerns.

Reflections

- This study highlights the range and complex dynamic of adversities and risk factors experienced by children from England and Wales who are placed in secure care in Scotland. Most of the children in this study had experienced emotional and physical neglect and abuse, sexual abuse, exposure to parental substance misuse and domestic abuse – with these issues often overlapping. Alongside this, children displayed complex mental health problems, including self-harm, and behaviours that are difficult to manage such as violence and aggression. In addition, they were at risk from a range of factors outside the home, including bullying, school exclusion, and criminal and sexual exploitation. These are some of the most vulnerable children in society, who experience more adversity in one year than most people experience in a lifetime.

- It is clear that the systems in England and Wales are struggling to respond to this group of children’s needs. Children sent to secure care in Scotland are often living hundreds of miles from their homes, and from their family and friends, most likely because an alternative placement that can keep them safe or meet their needs cannot be found any closer to home. In addition, almost all the children had experienced significant disruption and breakdowns in previous arrangements made for their care.

- Within Scotland, it is possible that new legislation will come into place – potentially as soon as 2023 – that will ban or significantly reduce the number of placements that are available in Scottish secure care centres to English and Welsh local authorities. This will mean the 25+ children placed in secure care in Scotland at any one time need to be accommodated elsewhere. Given existing pressure on secure children’s homes in England and Wales, there is an urgent need to consider alternative types of local provision for this group of children that can meet their needs identified in the report.

References

Bellis, M., Lowey, H., Leckenby, N., Hughes, K., & Harrison, D. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. J Public Health (Bangkok), 36. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdt038

Bellis, M., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Hardcastle, K. A., Perkins, C., & Lowey, H. (2015). Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey. J Public Health (Oxf), 37. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdu065

Downie, J. and Twomey, B. (2021). Secure children’s homes for welfare. National Youth Advocacy Service. https://nyas.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/WhoWeAre/Secure-Childrens-Homes-for-Welfare-NYAS-report-E%20(1).pdf.

Ford, K., Hughes, K., Hardcastle, K., Di Lemma, L. C. G., Davies, A. R., Edwards, S. and Bellis, M. A. (2019). The evidence base for routine enquiry into adverse childhood experiences: A scoping review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91, 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.007

Gibson, R. (2020). ACEs, places and status: Results from the 2018 Scottish secure care census. Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice. https://www.cycj.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ACEs-Places-and-Status.pdf

Gibson, R. (2021). ACEs, distance and sources of resilience. Children and Young People’s Centre for Justice. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/76788/

Martin, A., Nixon, C., Watt, K. L., Taylor, A. and Kennedy, P. (2021). Exploring the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in secure children’s home admissions. Child & Youth Care Forum, 1–15. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s10566-021-09660-y

Roe, A. (2022). What do we know about children deprived of their liberty? An evidence review. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/children-and-young-people-deprived-of-their-liberty-england-and-wales.