About

This is the summary of a themed audit involving 73 children (aged 10-17) from 49 families who were the subject of care proceedings issued by four local authorities in England and Wales in 2019/20. It is part of a series of work that aims to help build a better understanding of the reasons why older children and young people are being brought into care proceedings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff in the local authorities who undertook the audits of children’s social care records at a time when they were severely stretched amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. This report would not have been possible without their willingness to go yet another extra mile.

Disclaimer

Nuffield Family Justice Observatory has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Nuffield Family Justice Observatory or Nuffield Foundation.

In recent years there has been growing recognition of the increasing number of older children and young people coming before the family courts. This research seeks to identify the reasons why older children are being made subject to care proceedings, and the interplay between family justice, youth justice and the use of deprivation of liberty safeguards to protect children from harm within and outside their families. The overall aim is to understand what is working well and what changes are needed if the current systems and services are to respond well to the strengths and needs of older children and their families.

Introduction

This summary highlights the main findings of a themed audit of 73 older children (aged 10–17) from 49 families who were the subject of care proceedings issued by four local authorities with high levels of deprivation in England (north, south and London) and Wales in 2019/2020.1 It forms part of a series of work that aims to help build a better understanding of the reasons why older children and young people are being brought into care proceedings.

The research explored the following questions through a series of audit questions.

- What brought these children into the family justice system and what were the safeguarding concerns, both intrafamilial and extrafamilial?

- What plans were made for the children’s future, and what was the involvement of youth justice, health, education and other partner agencies?

- How are the needs of children and families being met, up to two years after the start of proceedings?

- What can be learnt from the achievements and challenges for local authorities and partners, and from the experiences of the children and their families?

The four local authorities completed their audit forms in March and April 2021. Findings were reviewed and analysed with each local authority during May and June.

Key findings

What do we know about the children and families concerned?

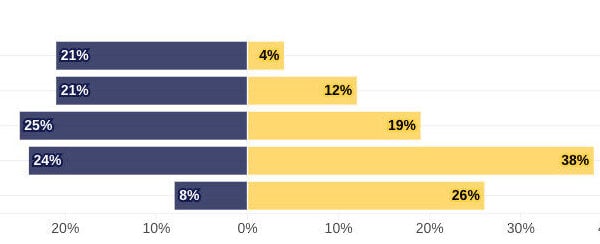

- Most of the 73 children in our study (68%) were aged 11–13. There was only one 17-year-old.

- Overall, there were slightly more boys in our study (38, 52%) than girls (35, 48%).

- Overall, nearly 80% of the children (58) were in proceedings with brothers or sisters. Just under half had older siblings in the proceedings and just under a quarter had younger siblings in proceedings. Nine children (12%) had siblings who were not in proceedings at all, and just six (8%) were single children.

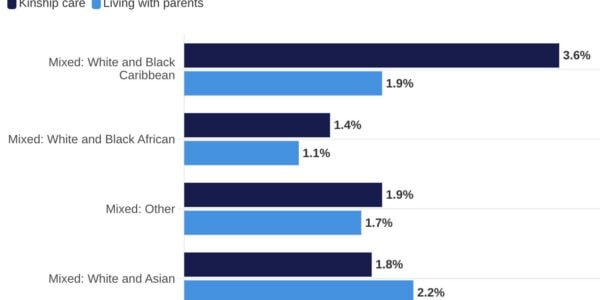

- In London and Wales, the children involved in the audit were mainly Black or of dual heritage, or from a broader range of different ethnicities. In the other areas (north and south England), the children in the cohorts were predominantly White.

- The vast majority of families (40 of the 49, 82%) were known to the local authorities at the time proceedings were issued. Most (32 of the 49, 66%) had been through the various stages of local authority support and safeguarding, and in almost half the families (31, 42%), children were already in care as proceedings started. For nearly a third of families (15, 30%), it was the second time the child or children had been in care proceedings. The gap between the first and repeat proceedings varied considerably—from one to twelve years.

This points to the importance of looking at some data through the family lens, as well as that of the individual child.

What brought children into the family justice system?

- All the children had experienced some degree of emotional harm, generally through the adverse effects of other grounds for proceedings: neglect (78% of families), domestic abuse (49% of families), physical harm (43% of families) and sexual abuse (10% of families).

- In terms of the ability of parents to provide safe care, there tended to be more than one factor at play: substance misuse and cumulative trauma featured most, each present for almost half the families (45% and 43% respectively). Poor parental mental health was a factor for over a third of families (35%). In addition, all the children had fractured relationships with one or both parents. These related to difficult and unresolved past and current experiences and to changes in family circumstances, often compounded by the separation and uncertainty prompted by the proceedings themselves.

- Extrafamilial concerns were present for a quarter of the children involved in the audit (18 children from 12 families, 25%).

The family stories showed that the children were not in proceedings because of either intrafamilial or extrafamilial harm. Rather, they were on a continuum of extrafamilial safeguarding concerns that varied from low to very high, and these external concerns were in addition to the intrafamilial reasons for issuing proceedings.

What plans were made for the children’s futures?

- In just over half the cases the judge had granted one or more extensions to the 26-week requirement for case completion. The reasons varied but included: long delays in trying to find suitable placements for children with serious and complex difficulties, time needed to assess different needs of children in sibling groups, and the use of a few extra weeks to test out plans (such as a return home or a move within the family network).

- At the end of proceedings care orders were made for just over half the children (38, 52%). In addition, all but one of the seven unfinished proceedings were anticipated to end with care orders too, given that the children were in (foster) care on interim care orders. Those with a care order were mostly living in fostering arrangements, including some who were placed with an approved kinship or connected person carer. The other children were in residential placements.

- Just under half of all the children (34) returned to a parent/parents or remained within their wider family network. The decisions made by the court for these children included supervision orders, special guardianship orders, child arrangement orders, and kinship foster care arrangements under a care order.

- Placement moves were also recorded on the audit forms. Almost half the children remaining in care after the end of proceedings stayed where they were living, and so experienced no move. These children were overwhelmingly those whose placement became a long-term foster/kinship care arrangement with the granting of a care order. Almost two-thirds of these children had had no more than two placements during their time in care. The children in kinship fostering arrangements had experienced the least change in placement.

- Children who experienced more than four foster placements since being in care were likely to then move to a residential setting. We found a general lack of suitable placements for older children—especially worrying where public safety or welfare considerations were driving the thinking about deprivation of liberty. Acting in an emergency was an added burden in terms of finding a suitable placement.

- For some children who spent time in a secure setting during or after proceedings (e.g. in the youth secure estate, secure children’s homes, or alternative placements depriving them of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court), it had the potential to provide opportunities for them to engage with interventions and education services, and bring about positive change. We found that positive change seemed more likely when the deprivation of liberty was made in a planned way, as part of a clear strategy for a child, rather than being emergency action because no bed was available in a secure children’s home.

What was the involvement of youth justice, health, education and other partner agencies?

- We found examples of highly imaginative, multi-agency care packages to support and safeguard some children.

- There was evidence of youth justice involvement for 12 of the 73 children (16%). This ranged from minor offences with early intervention responses directed at specific risks to serious offences that resulted in older children spending time in the youth secure estate. It may be that the audit forms underrepresented the early intervention responses by the police and/or youth justice services. We add this caveat because it became clear that there was no easy way for auditors to find more than very basic information in the children’s services records about the involvement of youth justice services.

- We found many examples of school as a positive factor. It was described as a safe haven, a source of continuity in times of disruption and stress, with teachers who boosted confidence and progress in children and parents. We were surprised to find no mention of education welfare services, bar one reference to a mother having been prosecuted for her children missing school.

- It was notable that some children’s health needs (across the age range) were identified only after proceedings had started and the children were in care. This occurred in separate cases involving attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, sleep disorder and complex trauma. Auditors noted that some children were reluctant or unwilling to accept child and adult mental health service (CAMHS) and other offers of help. In the main, however, those who were enabled to access support began to make some progress. Some children were being helped to explore their feelings in creative ways, for example through songwriting and sport.

Natasha’s story: a life of trauma and a glimmer of hope at 13

When Natasha’s parents separated she stayed with her mother. In primary school, Natasha said she had been sexually abused by a male family member. He was found not guilty after a criminal trial. Natasha’s mother always said she did not believe her daughter’s allegations and professionals wondered if she had experienced abuse herself as a child. Children’s services worked with the family under a child protection plan, but things deteriorated, and the local authority moved to pre-proceedings. A family group conference (FGC) led to Natasha moving in with her father. She seemed to settle down and made a smooth transition to secondary school.

In Year 8 (age 12), Natasha started staying out late. She was found with cannabis and she became secretive with her phone. She often had money beyond what could be expected. She started to skip school and, when there, her poor behaviour resulted in a short-term and then permanent exclusion. She moved back in with her mother, but then missed two school terms and did not get on with her sisters. She set fire to the home and became beyond the control of both parents. At a further FGC, other family members felt that Natasha was too difficult for them to look after, and the local authority agreed with their conclusion.

Natasha came into care under section 20 [Children Act 1989] with agreement from both parents but she moved rapidly through seven foster, residential and other placements because of her behaviour, which included assaults on carers and other children and fire setting. She went missing frequently and during these episodes she was assaulted both physically and sexually.

The local authority applied successfully for a care order and, during the proceedings, for a secure accommodation order, but there was no secure placement available. She was held in an unregistered setting, with the High Court having sanctioned deprivation of her liberty for eight days because of the risk to herself and others.

The youth justice service was involved, on account of convictions for assault, as was CAMHS, because of her self-harm and suicidal feelings that resulted in several visits to hospital. In her current therapeutic residential placement, she is being treated for post-traumatic stress syndrome.

There are signs that Natasha is finding the current support helpful: for the past six months she has had better attendance in her current educational provision and is completing her GCSEs, with some good grades expected. In particular, she enjoys singing, song writing and the performing arts, and these have given her a new focus. Her relationship with both parents remains fragile but there is some intermittent phone contact. Natasha has a care advocate and is becoming involved with the local children in care group.

Data gaps and limitations

We recruited a range of local authorities and a satisfactory cohort size (73 children in 49 families), and the topics and findings resonated with other evidence. However, there are caveats to bear in mind when interpreting

the results.

Firstly, the information held by the local authorities varied in quality and detail, resulting in variation in the ease with which the local auditors could locate either relevant information about the children or administrative data about the cohort in the context of their proceedings overall. There was variation too in the number of children in each local authority cohort and in the proportion of sibling groups as opposed to single children in the audit age range.

Secondly, this was predominantly a file exercise (of electronic social care records completed and held by children’s services, and supplementary information from legal planning meetings and reviews on children in care). Some extra information was included because an auditor knew the children and family concerned or checked with a colleague who did. It follows that there has been no exploration of the extent to which the children, parents or other carers (and other agencies) took a similar view to that transferred to the audit forms about what had happened and why, or about what might have been done differently. This was not our remit, but it does leave a gap in perspectives—a limitation that has been challenged by others.2

Thirdly, as the audit focused only on the children aged 10–17 brought into care proceedings during the audit year, it excluded three other groups of local children of the same age: those already in the care of the local authority, those known to children’s services as children in need (under section 17 of the Children Act

1989), and all the other children in the local authority’s general population. This considerably limits the overall picture of work that safeguarding agencies are likely to be undertaking to disrupt and prevent harm to children from within or outside their families.

Fourth, the audit included only three local authorities in England and one in Wales. Findings may therefore not be generalisable to other areas.

Reflections

Treading water is not enough

We must make and take opportunities to help children differently, through earlier attention to the difficulties that face those closest to them. This would include a renewed focus on tackling parental needs as soon as they arise, through a family lens and with greater understanding across all services of complex trauma and its impact on how people respond when they feel under threat and in distress.

Action is needed:

- To attend to parental needs relating to substance misuse, domestic abuse and poor mental health and tackle the related underpinning poverty and disadvantage faced by families in everyday life.

- To offer better support when children return home on a supervision order, given the high rate of those cases becoming repeat proceedings.

- To act sooner rather than later. Being prepared to take a case to the family court when there are clear indications that things are highly likely to continue getting worse is one example. Another is providing an intensive support programme at home, to avoid unnecessary prolonged family separation.

- To strengthen support to vulnerable children in Years 5 and 6, before transition to secondary school.

- To build earlier connections between children’s services and the youth justice system.

- To provide an up-to-date literature review of the specific issues relevant for children and families in the overlapping but separate (and sometimes siloed) systems and services of family justice and youth justice.

Provide safe havens

We must resolve to bridge the yawning gap in suitable provision for older children with complex difficulties who need to be in care. The adverse impact on their safety and development, and the parallel frustration of practitioners, managers, and often their families, in finding suitable placements and provision, have confronted us for too long.

Action is needed:

- To ensure that local authorities have access to small, safe, specialist local homes where young people can be helped to deal with their past experiences and feel inspired to look forward to the future.

- To build on the safety that school provides for some children and parents.

- Given that absence from school is a trigger for heightened vulnerability, we must actively challenge policy and practice around school exclusion.

- To acknowledge and harness what secure accommodation can provide for some children—including, as the audit shows, helping to compensate for lost education, enabling children to engage in activities and self-development programmes, allowing children to get warm support from staff, and enabling access to therapeutic help after release. Further research is needed to understand outcomes for children in secure accommodation, and what type of care is most beneficial.

Maintain the lifeline

A crucial vulnerability to extrafamilial harm relates to losses that stem from weak or poor relationships, separation, bereavement and other traumatic events or circumstances. It follows that a top priority in supporting children is a concerted effort to mend and sustain existing relationships so that children retain as many links as possible with people who love them, and so that they get the best possible support to restore fraught and fractured relationships with their parents, brothers and sisters, and other relatives. Added to this is the value of professionals being curious about children’s lost connections and being diligent about exploring what they might have to offer.

Action is needed:

- To learn from the experiences and views of children and those close to them who have waited a long time—in the view of auditors sometimes far too long—for the welcome relief from burdens they have been struggling with. And to learn, too, about the need for, and experience of, being drawn back to the place that is home and the people who are family, and of understanding and dealing with the tensions, emotions, risks and benefits involved.

- To learn from what the audit has highlighted about successful practice using family group conferences and other family decision-making meetings, and the added value of that work being led, driven and supported by agency policies and strong leadership committed to a family-inclusive approach. We recommend the continued promotion of—and support for—this model of work, and for professional practice in and out of court that values the importance of seeing parents and older children as partners with professionals in identifying and tackling the problems they face.

1 The authorities are referred to in Figure 1 as Local authority A, B, C and D.

2 Note the recommendation of the Care Crisis Review: ‘That there is a presumption that the methodology of research studies exploring practice with, and outcomes for, children and families incorporates the experiences of family members’. See: Family Rights Group. (2018). Care crisis review. Options for change. Available from: https://frg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Care- Crisis-Review-Options-for-change-report.pdf

-

Research In Practice

Research In Practice