Acknowledgements

We are particularly indebted to the children and young people for sharing their stories and reflecting on what were often traumatic, disruptive, and tumultuous times in their lives.

We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to the social workers, support workers, personal advisors (PAs), and other facilitators who helped with the workshops and provided ongoing support to the young people who took part in this project.

Introduction

“Every young person who has been in care gets ‘care files’, but these are the files that social services keep on the young person; they only offer one perspective. What we have done here is created our own care files, our own story of how the system can change based on our journeys.” (Young person, 25)

This report summary presents the key themes and insights drawn from a number of co-designed workshops and interviews with 24 older children and young people who are either being supported by the care system, or who were supported by the care system in England and Wales between the ages of 10 and 17. The majority had entered care via Section 31 of the Children Act 1989 (CA 1989), with a smaller number entering under voluntary arrangements via Section 20 (CA 1989) and Section 76 of the Social Services and Well-being Act 2014 in Wales.

We sought to understand more about the support older children, young people and their families received before and after entering care. They told us how different systems work together, and how these systems and services could change in the future to better support those who are cared for and supported in their teenage years. The overall aim is to understand what a system that responds well to the strengths and needs of older children and their families would look like.

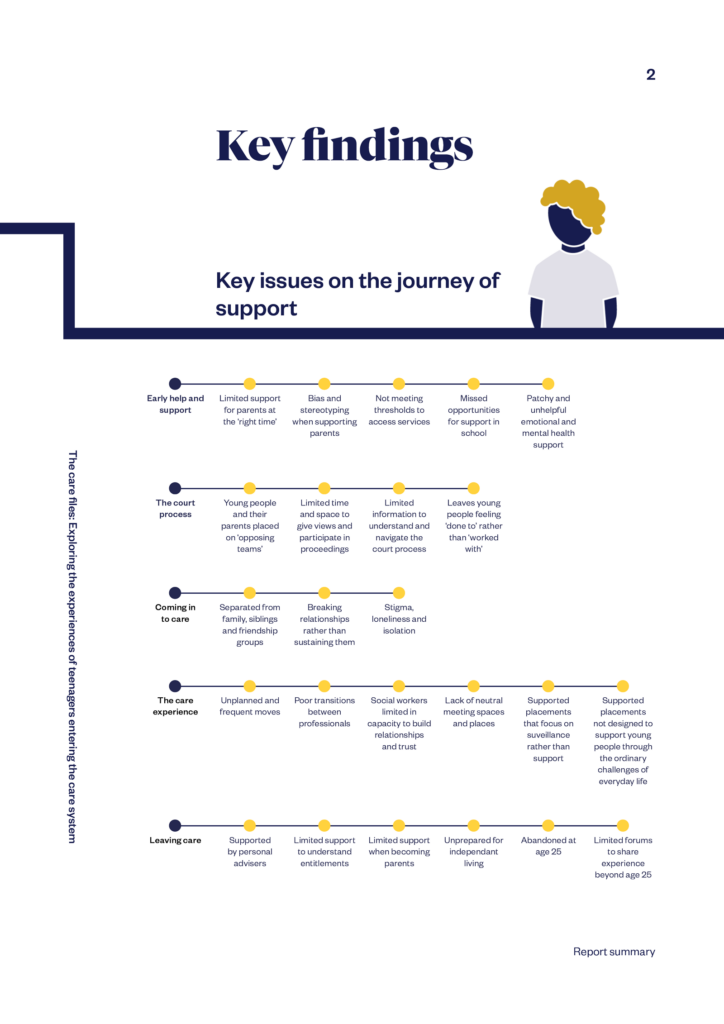

Key findings

Young people’s wishes for the future

“This isn’t just about social workers, key workers, foster carers, or care homes. This is about everyone involved in the system and beyond. If a young person doesn’t get their needs met and isn’t able to move on from their trauma, they then take that on through their whole lives, including with their own children. It then becomes a vicious, vicious cycle. It just goes round and round. Somewhere along the line, somebody is going to have to say ‘enough is enough’ and make some serious changes. Because at the end of the day, it’s not just this generation’s lives that can be impacted by the system, it’s the generations after.” (Young person, 19)

It is of concern that many of the things young people are asking for are not already happening in line with regulations or statutory guidance as a matter of course. That they have been raised in recent discussions suggests there is much more to be done to ensure practice is in line with guidance. Any future system that cares for older children and young people should …

1. Support and enable young people to be actively involved in decisions being made about their care – and at the very least help them understand the reasons behind decisions.

Even if young people do not agree with the decisions made about them in the care system, feeling heard is important for future well-being. They should be given information about their rights and options before each key transition toward adulthood. Good support should be tailored and authentic rather than general and formulaic to comply with guidelines. Young people should be asked their views privately and before decisions have been made – they should be communicated with as young adults and told the truth. This goes beyond being ‘consulted’ to becoming an active participant in the decision-making process. We heard that this is not happening for all young people.

All young people want to know who is making decisions about their care, and at the very least, be able to understand how any decisions have been reached – including decisions made in the family court. More information should be provided to young people about the role of the family court, and the different legal professionals involved, in order to help them navigate the court process.

Cafcass and children’s social care should consider using shared digital

systems to allow for a young person’s voice, preferences and feedback to

be relayed to judges in the family court over a longer period of time before proceedings, rather than solely relying on a short session with a social worker and children’s guardian.

2. Trust young people to build relationships with the professionals in

their lives.

Many of the young people involved in this project had supportive relationships with their key workers and social workers, and most appreciated the enormous emotional, time and capacity pressures they faced. However, even in these circumstances it was felt that these relationships were limited by the professional fear of creating dependency and relationships that in effect made a young person feel like a younger child who could not be trusted, and leading to a lack of engagement.

In a future system, young people should be trusted to build equal, consistent relationships. This does not mean a professional needs to be available on the phone every day, or to become the primary person in a young person’s support network. Instead, the system should allow professionals to engage in a more rounded, equal relationship that is more appropriate for the young person’s age. This might involve meeting in neutral spaces rather than local authority buildings, using accessible plain language when speaking about living arrangements and carers, and showing an interest in all aspects of the young person’s life.

Professionals should give ample notice when they are due to leave a post

or go on an extended period of leave. Transition and handover meetings

should take place between the young person and both the current and

new professional.

3. Provide young people with both care and support when approaching 18.

Most children in care are looked after in children’s homes or by foster carers – but the number of children housed in supported (unregulated) accommodation is growing (Children’s Commissioner’s Office 2020). These are settings that are intended to support young people between care and independent, adult life.

High quality forms of supported accommodation can be a good option for some young people, when considered following a concerted assessment process that includes a consultation with each young person, and when regular monitoring is in place to ensure the arrangement is offering positive and caring experiences (Become 2021)

However, we heard that supported placements often do not provide the care and emotional support 16 and 17-year-olds need to ‘move on from [their] trauma’ when entering care later in childhood.1 We also heard that they did not provide ‘support’ either, geared rather more towards surveillance than helping young people through the ordinary challenges of everyday life. Many young people questioned whether professionals were able, or willing, to offer guidance or assistance on issues they might have at school, or socially or financially when disruptive life events occurred.

4. Help young people maintain relationships with their families and

communities.

We know that many young people will continue to have a relationship with their birth families even if their living arrangements while in care have been a positive experience. This is particularly true for young people who enter care as teenagers.

Young people must be supported to maintain connections with the networks they have built before coming into care – siblings, birth parent(s), extended kin relationships or members of the community. While in some instances ongoing contact and relationships with birth families may not be appropriate or desired, all young people must be supported to understand and address what ‘family’ means for them and given time and space to ensure those relationships are maintained.

A number of young people spoke passionately about one particular

adult – usually a key worker, teacher or staff member in school or college

– that supported them during their time in care. Where possible, these

relationships should be nurtured and maintained, even when a young

person moves between homes.

5. Encourage and support young people to understand their rights and

entitlements upon leaving care.

Many of the young people valued the support given to them by their personal advisers, providing them with a stable, caring relationship after they had ‘left care’. However, despite these positive relationships, some felt that finding out about rights and entitlements as a child in care or as a care leaver remained difficult.

Organisations such as Coram Voice are working to help young people understand their rights and entitlements, yet we heard many young people say that they struggle to navigate this complex maze. It was suggested that all young people should be offered time with their local authority’s children, rights and participation officer (or equivalent) to understand their entitlements before they reach 16, 18 and 25.

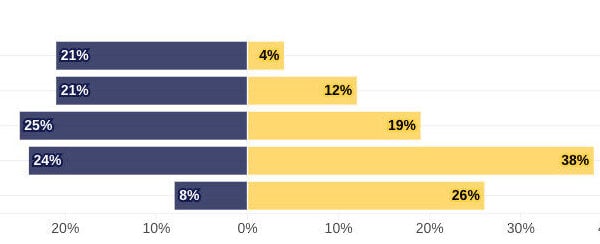

Not all young people who leave care are entitled to the same support after the age of 18. Those who are placed with relatives under a special guardianship order are currently not entitled to the same support and entitlements as those who have spent time under a care order or who have been in foster or residential care. Those who have been supported after the age of 16 for less than 13 weeks also fall into a grey area when reaching the age of 18. The same duties should be extended to all care leavers.

6. Provide young people with the corporate parenthood they need to

thrive beyond the age of 25.

If the state makes the decision to intervene in a young person’s life and

become their ‘corporate parent’, society has a responsibility to ensure

that support continues beyond the age of 25 and well into adulthood. We have an ethical and moral responsibility to provide young people with flexible emotional, relationship and financial support in their communities throughout their adult lives.

7. Provide young people with the mechanisms to provide support to

others and to have their voices heard beyond the age of 25.

Many of the young people who engaged in this project expressed feelings of frustration that the avenues available to them to discuss their experiences and offer support to younger children in care were severely limited. Most noted that their local children in care council placed an upper age limit on participation of 24 or 25.

Local authorities should provide regular forums and spaces for those over 25 to come together and engage with those currently in care and to share their insights, concerns and ideas about how the system can improve.

Next steps

The report on which this summary is based, together with other materials created during this project, represent the first step in a longer engagement with stakeholders at all levels of the child welfare system to explore different and innovative ways of supporting older children, teenagers and young people.

The five advisory group co-researchers will present the key themes from the project and discuss how the system can improve via a series of collaborative circles. These circles will feature representatives from legal and social work professions as well as other agencies that have an influence on the experience of older children and young people in care, such as the police, mental health practitioners, and those working in secondary and further education.

Adolescence is a unique stage of development that presents particular challenges for those responsible for older children and young people supported by the care system. For social workers, parents and carers, managing increasingly complex relationships with friends and birth families during this period, while striking a balance between promoting independence and offering protection, remains an ongoing challenge (Tunnard and Brown 2021).

Through a series of reports and other engagement activities, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory is bringing together existing and emerging evidence, combined with the insights of young people, parents and carers, professionals and other experts by experience, to identify ways to improve provision for those who are supported by the care system at an older age. While our focus begins with looking at the care system and children’s social care, we intend to look more widely at other systems and services such as youth justice and support for separated migrant children.

References

Become. (2021). Being in care. https://becomecharity.org.uk/care-thefacts/being-in-care/

Children’s Commissioner’s Office. (2020). Unregulated. Children

in care living in semi-independent accommodation.

Tunnard, J. and Brown, C. (2021). Why are older children in care

proceedings? A themed audit in four local authorities. Nuffield Family

Justice Observatory. https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2021/09/why-are-older-children-in-care-proceedings-a-themedaudit-in-four-local-authorities-report-1021.pdf

Full reference list available from the main report: https://www.nuffieldfjo.

org.uk/resource/the-care-files-exploring-the-experiences-of-teenagersentering-the-care-system

Advisory group co-researchers

Caitlin Wakeman

Chloe Rees

Francis Tutson

Ikesha Tuitt

Michael Clarke