Data tracker

Filter by

Chart of the month

Publicly funded mediation has declined since 2013

Publicly funded mediation has seen a substantial decline since 2013, with a 60% drop in assessments over 12 years, and a halving of successful agreements.

This fall is frequently attributed to the removal of legal aid for most private law cases, as families were most often signposted to mediation through their lawyers. Following the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO), the number of families starting mediation has remained low, however a small uptick in assessments in 2024/25 may indicate some change in this area. Initiatives such as the introduction of a voucher scheme in 2021 which offers up to £500 per family towards mediation costs, have not been properly tracked to establish whether they are effectively diverting families from court.

Mediation is not appropriate for all families and particularly may not be for families who have experienced domestic abuse, which is common in family court proceedings. Recent research by the Domestic Abuse Commissioner found that 87% of closed case files, and 73% of observed private law cases feature domestic abuse, indicating that a large proportion of families could be exempt from mediation. Between April 2019 and March 2024, only 35% of private law applicants attended a mediation information assessment meeting, as a large proportion claimed exemptions (NAO, 2025).

The decline in publicly funded mediation raises wider questions about how well families have access to appropriate guidance and support in the family courts, not just through mediation, but legal representation or otherwise. Efforts to divert families from court, or improve families’ experiences of feeling heard during proceedings, risk being undermined if early, adequately resourced forms of advice and assistance are not accessible.

Publicly funded mediation has seen a substantial decline since 2013, with a 60% drop in assessments over 12 years, and a halving of successful agreements.

This fall is frequently attributed to the removal of legal aid for most private law cases, as families were most often signposted to mediation through their lawyers. Following the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO), the number of families starting mediation has remained low, however a small uptick in assessments in 2024/25 may indicate some change in this area. Initiatives such as the introduction of a voucher scheme in 2021 which offers up to £500 per family towards mediation costs, have not been properly tracked to establish whether they are effectively diverting families from court.

Mediation is not appropriate for all families and particularly may not be for families who have experienced domestic abuse, which is common in family court proceedings. Recent research by the Domestic Abuse Commissioner found that 87% of closed case files, and 73% of observed private law cases feature domestic abuse, indicating that a large proportion of families could be exempt from mediation. Between April 2019 and March 2024, only 35% of private law applicants attended a mediation information assessment meeting, as a large proportion claimed exemptions (NAO, 2025).

The decline in publicly funded mediation raises wider questions about how well families have access to appropriate guidance and support in the family courts, not just through mediation, but legal representation or otherwise. Efforts to divert families from court, or improve families’ experiences of feeling heard during proceedings, risk being undermined if early, adequately resourced forms of advice and assistance are not accessible.

There are more babies and young children in public law proceedings than in care

The majority of public law proceedings in the family courts are for younger children, in stark contrast to the population of children in care, where most are over the age of 10.

These differences can be partially explained by the outcomes for younger children in proceedings; a high proportion of cases involving children under a year old in England and Wales will result in adoption or a special guardianship order. There has also been an increase in older children in care, particularly those on voluntary or consent-based arrangements, who have not come through the family justice system (section 20 of the Children Act 1989 in England and section 76 of the Social Services and Well-being Act 2014 in Wales).

The majority of public law proceedings in the family courts are for younger children, in stark contrast to the population of children in care, where most are over the age of 10.

These differences can be partially explained by the outcomes for younger children in proceedings; a high proportion of cases involving children under a year old in England and Wales will result in adoption or a special guardianship order. There has also been an increase in older children in care, particularly those on voluntary or consent-based arrangements, who have not come through the family justice system (section 20 of the Children Act 1989 in England and section 76 of the Social Services and Well-being Act 2014 in Wales).

Vocational pathways into higher education are more common for care leavers

November is Care Leavers Month! In England and Wales, there are more than 50,000 care leavers aged 17-21. Care-experienced children and young people often face disrupted educational pathways, including household and school moves which can present barriers to continued education; 14% progress to higher education by age 22, compared to 56% of the general population.

For those entering higher education, a greater proportion (over a third) did so through vocational pathways (such as NVQ Level 3), rather than traditional pathways (entry with academic qualifications e.g. GCSE & A levels).

This data highlights the potential of flexible, vocational pathways to increase educational inclusion for young people with experience of children’s social care.

November is Care Leavers Month! In England and Wales, there are more than 50,000 care leavers aged 17-21. Care-experienced children and young people often face disrupted educational pathways, including household and school moves which can present barriers to continued education; 14% progress to higher education by age 22, compared to 56% of the general population.

For those entering higher education, a greater proportion (over a third) did so through vocational pathways (such as NVQ Level 3), rather than traditional pathways (entry with academic qualifications e.g. GCSE & A levels).

This data highlights the potential of flexible, vocational pathways to increase educational inclusion for young people with experience of children’s social care.

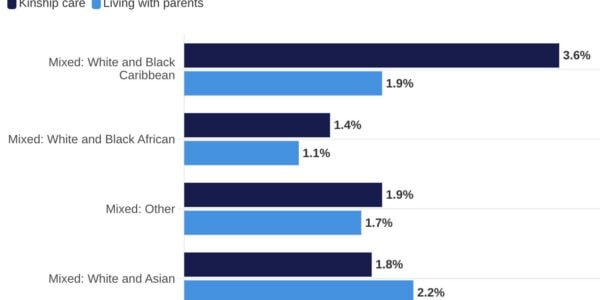

Mixed ethnicity children are overrepresented in kinship care

October marks Kinship care week! Kinship care is when a child is raised by relatives or friends, because their parents are unable to do so. According to the 2021 census, roughly 121,000 children were living in kinship care, and the majority of these children (59%) lived with at least one grandparent.

Census data shows that Black and mixed ethnicity children are overrepresented in kinship care, compared to children living with their parents. This mirrors previous research in the family justice system, which has highlighted that these groups are over-represented in both the family courts, and in the care population.

The census captures information from nearly all households in England and Wales, so provides a picture of most children living in kinship care under a variety of different legal arrangements (such as kinship foster carers, special guardianship orders, or other informal arrangements that may not go through the family courts).

Read more about this data, and what it tells us about kinship families here.

October marks Kinship care week! Kinship care is when a child is raised by relatives or friends, because their parents are unable to do so. According to the 2021 census, roughly 121,000 children were living in kinship care, and the majority of these children (59%) lived with at least one grandparent.

Census data shows that Black and mixed ethnicity children are overrepresented in kinship care, compared to children living with their parents. This mirrors previous research in the family justice system, which has highlighted that these groups are over-represented in both the family courts, and in the care population.

The census captures information from nearly all households in England and Wales, so provides a picture of most children living in kinship care under a variety of different legal arrangements (such as kinship foster carers, special guardianship orders, or other informal arrangements that may not go through the family courts).

Read more about this data, and what it tells us about kinship families here.

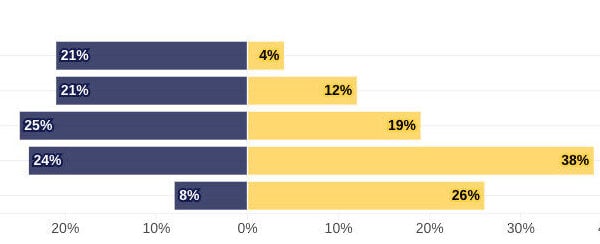

80% of cases in private family law proceedings involve at least one unrepresented party

Full legal representation is lacking in the majority of private family law cases, with 80% of cases involving at least one person who is unrepresented. The number of cases where neither applicant nor respondent has legal representation has risen substantially over the last decade, from 13% in 2013, to 39% in 2024. This increase was trigged by the introduction of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, which resulted in the removal of eligibility for legal aid for the majority of private law cases, and came into effect in April 2013.

Access to legal aid in private family law is now restricted to cases where there are issues concerning domestic abuse or child abuse, in addition to stringent financial means testing. This has had knock-on effects, increasing pressures on the family courts as more applicants become litigants in person and require greater supports to navigate proceedings, as well as on other services such as community services or children’s social care when families struggle to resolve disagreements. Since May 2025 a cyber-attack on the Legal Aid Agency has further hampered access to justice, as systems remain offline and legal professionals are unable to be paid for legal aid work, adding additional strain on the system.

Full legal representation is lacking in the majority of private family law cases, with 80% of cases involving at least one person who is unrepresented. The number of cases where neither applicant nor respondent has legal representation has risen substantially over the last decade, from 13% in 2013, to 39% in 2024. This increase was trigged by the introduction of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, which resulted in the removal of eligibility for legal aid for the majority of private law cases, and came into effect in April 2013.

Access to legal aid in private family law is now restricted to cases where there are issues concerning domestic abuse or child abuse, in addition to stringent financial means testing. This has had knock-on effects, increasing pressures on the family courts as more applicants become litigants in person and require greater supports to navigate proceedings, as well as on other services such as community services or children’s social care when families struggle to resolve disagreements. Since May 2025 a cyber-attack on the Legal Aid Agency has further hampered access to justice, as systems remain offline and legal professionals are unable to be paid for legal aid work, adding additional strain on the system.

Over half of school-aged children in care have special educational needs

Special educational needs (SEN)s encompass a range of needs and disabilities including neurodivergence (such as ADHD and Autism), cognitive, socio-emotional and mental health difficulties, physical disabilities and sensory difficulties. A high proportion of children in care have SEN. As the graph shows, over half (57%) of children in care have special educational needs, compared to 18% of all children. This suggests that approximately 3% of all children with special educational needs are those in care, around four times higher compared to the percentage of children in care in the general population (less than 1%). Since 2017/18, the number of children with special educational needs has steadily increased, with a sharper rise among looked after children (4.7%) compared to all pupils (3.5%).

Special educational needs (SEN)s encompass a range of needs and disabilities including neurodivergence (such as ADHD and Autism), cognitive, socio-emotional and mental health difficulties, physical disabilities and sensory difficulties. A high proportion of children in care have SEN. As the graph shows, over half (57%) of children in care have special educational needs, compared to 18% of all children. This suggests that approximately 3% of all children with special educational needs are those in care, around four times higher compared to the percentage of children in care in the general population (less than 1%). Since 2017/18, the number of children with special educational needs has steadily increased, with a sharper rise among looked after children (4.7%) compared to all pupils (3.5%).

Infographic

What do we know about children in the family justice system?

Our regularly updated infographic highlights what we know, and what we don’t know, about children’s journeys through the family justice system based on national administrative data.