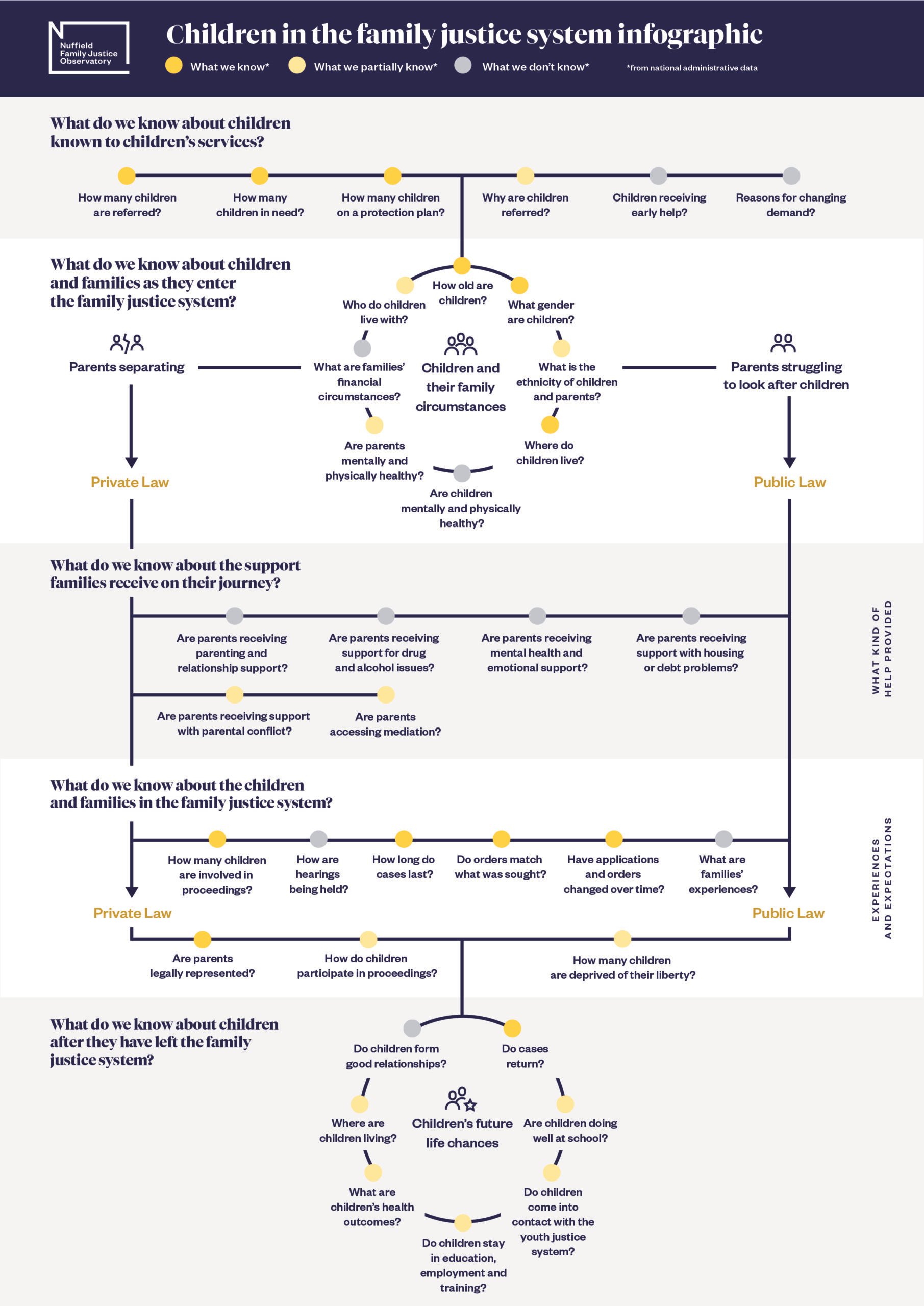

Children in the family justice system infographic

Our regularly updated infographic highlights what we know, and what we don’t know, about children’s journeys through the family justice system based on national administrative data.

Overview

The infographic tries to answer the question; what do we know about children in the family justice system from national administrative data?

How to read the infographic

The infographic is structured as a series of questions across key points in a child’s journey through the courts and allied systems and services.

- What we know: We have extensive national data which allows us to comprehensively answer the question.

- What we partially know: We have some national data, but it does not allow us to answer the question for both public and private law or for both England and Wales.

- What we don’t know: We have no available national data to answer the question.

These questions are categorised using colours, like this:

Click on any (+) bubble to show the latest available data related that particular question.

What do we include?

In most cases data in the infographic is drawn from publicly available administrative data held by different government departments in England and Wales. In some cases, we draw on one-off analysis of safeguarded administrative data that has been undertaken by researchers.

We have written a downloadable data overview which provides more detail on the national administrative data cited in the infographic.

This infographic is updated in line with administrative data release dates, usually quarterly

What do we know about children known to children’s services?

In most cases in England and Wales the statutory child protection process for a child and their family does not begin with public law proceedings – children are sometimes already known to local children’s services.

What do we know about children and families as they enter the family justice system?

According to data from the Ministry of Justice, in 2024 the family courts received applications about the future relationships of 105,227 individual children in England and Wales.

Linking data about these children will give us a much richer evidence base for determining the effectiveness of the system and identifying ways to improve it

Children and their family circumstances

What do we know about the support families receive on their journey?

Various types of support for families are necessary to prevent family problems form escalating — and, where possible, to be resolved — so that there is no need for an application to be made to the family court.

Potential public/private law overlap

Private law applications to the family court usually involve separated parents who are struggling to agree arrangements for their children. Almost 10 per cent of these applications feature people who are not parents. This is a significant minority of cases, with around 5,500 such applications made each year in England and 300 in Wales. Families involved in child arrangements applications where children are being cared for by adults who are not their parents, may have similar circumstances to public law cases. For example, they are likely to represent situations where there were children’s safety or welfare concerns which indicates a possible overlap with the circumstances of care cases. A recent study found a significant proportion of the types of private law cases that may represent child safety/welfare concerns – at least 38 per cent in England, but potentially substantially more. This is evidence of a potential public/private law overlap. (Cusworth et al. 2023).

What do we know about the children and families in the family justice system?

The family justice system routinely collects data about the way that it works — such as how many cases come before the court and how long each case takes — but does not collect information on children’s and families’ own expectations of system and wether their expectations are met.

What do we know about children after they have contact with the family justice system?

The only indicator or feedback that those working in the family justice system have about the impact of decisions on children is whether they subsequently return to court again. Yet by linking data already collected, we can provide insights into children’s short, medium and long-term outcomes.

Children’s future life chances

Number of children referred

Referrals

In (the year ending 31 March) 2025, the rate of referrals in England had started to rise, following falls that were seen after a peak in referrals in 2021/22 after the pandemic.

How many children are referred to children’s services each year?

Rate of referrals in the year per 10,000 children under 18, England, 2009/10 – 2024/25

A re-referral occurs when a child is referred within 12 months of a previous referral.

Re-referrals data is not published for Wales.

Around a quarter of children who had a previous referral (in the last 12 months) are re-referred to children’s social care.

Number of children re-referred

Percentage of re-referrals in the year, England, 2009/10 – 2024/25

How many children are in need or in need of care and support?

England

A child in need is defined under the Children Act 1989 as a child who is unlikely to reach or maintain a satisfactory level of health or development, or their health or development will be significantly impaired without the provision of children’s social care services, or the child is disabled.

In 2025 (as at 31 March), the rate of children in need was at its lowest level since 2019/20, following sustaining rises seen after the Covid-19 pandemic.

The demographics of the children in need population is changing. It is ageing; and those aged 10 and over now make up the majority in England. In 2025, young people aged 18 or over who were still receiving care and accommodation or post-care support from children’s social care services accounted for 15% children in need. It is also becoming more diverse; a higher proportion of Black, Asian and Mixed-ethnicity children are now classed as children in need than in 2015, and are over-represented in comparison to the general population.

How have rates of children in need in England changed over the past 10+ years?

Children in need per 10,000 population under 18 at 31 March, England, 2009/10-2024/25

Which local authorities have the highest and lowest rates of children in need?

Children in need per 10,000 population under 18 at 31 March 2025, England, local authorities

What is the age distribution of children in need in England?

% children in need by age group, England, 2014/5 to 2024/5

What is the ethnicity of children in need in England?

% of children in need by ethnicity of children in need, England, 2015-2025

How many children receive care and support in Wales each year?

Children receiving care and support per 10,000 under 18, Wales on 31 March, 2016/17- 2022/23

Number of children on a child protection plan or register

England

The number and rate (per 10,000 children) of children on protection plans peaked in 2018 (figure as at 31 March) and, has seen small rises and falls since then. Rates in 2025 (as at 31 March) are the lowest since 2013.

How many children are on a child protection plan in England?

Children on a children protection plan per 10,000 under 18 at 31 March, England 2009/10-2024/25

How often are children on a protection plan subject to a second or subsequent protection plan in England?

Children who became the subject of a plan for a second or subsequent time (%), England 2013/14 – 2024/25

- physical abuse

- emotional or psychological abuse

- sexual abuse

- financial abuse

- neglect

In Wales the number of children who are on a subsequent protection plan is not reported

How many children are on the child protection register in Wales?

Number of children on children protection register per 10,000 under 18 at 31 March, Wales 2016/17-2023/24

Why are children being referred to services?

In England, the proportion of children with abuse and neglect as their primary need has increased by 23% (11 percentage points) between 2012/13 and 2024/25. Meanwhile the proportion of children referred because of their disability, their parents disability or family functioning has decreased in the same period.

What are the most common primary needs of children identified at assessment following referral to children’s services in England?

Proportion of children in need by primary need at assessment as at 31 March, England, 2013/14-2023/24

Are the reasons for being referred different for older children?

The levels and complexity of need are more diverse amongst older children.

Using the primary need at assessment as a measure, the needs of children aged 10 and older in England are more diverse than those aged nine or younger, including factors relating to family stress, disability/illness, absent parenting and disruptive behaviour.

Similar patterns have been found in Wales.

Children receiving early help?

Statistics on the number of children receiving early help (locally defined offer for children not meeting statutory thresholds) are not collected nationally.

Why is the number of children known to children’s services changing?

How old are the children?

Public law

Just over one in five children in care proceedings is aged under one. However, in recent years there has been an increase in the number of older children (10+) subject to care proceedings.

What is the age distribution of children involved in public law applications?

As in public law, most children involved in private law applications in England and Wales are aged nine or under. However, in recent years we have witnessed a growing proportion of applications being made for older children.

NOTE: 2022 is based on figures for first two quarters

What is the age distribution of children involved in private law applications?

What gender are children?

Boys slightly outnumber girls in the family justice system (for both public and private law).

But girls are more likely than boys to enter the system via public law proceedings in their teenage years.

In 2019 Cafcass amended how they record gender to enable children and young people to indicate if they preferred to identify as being gender neutral, non-binary, or transgender.

This data was published for the first time in 2021. 0.2% children in public law selected this option and 0.1% in private law in 2020/21. These figures increased to 0.4% of children in public law and 0.2% in private law in the year 2021/22.

What is the gender distribution of children involved in public and private law cases?

What is the ethnicity of children and parents?

England

There is limited data about the ethnicity of children and families who come into contact with the family justice system.

This data is not published by the Ministry of Justice or HMCTS. From 2016/17 Cafcass England began recording ethnicity data more systematically.

In 2021/22 ethnicity data was recorded for 96.4% of children in public law proceedings and 86.6% of children in private law proceedings in England.

Cafcass Cymru have recently begun recording ethnicity data, however these data are currently not sufficient quality for research on current or historical trends. Data linkage approaches have been used in Wales to explore the ethnicity of children and families in the family justice system.

Overall, White children and adults are underrepresented in public and private law in England, compared to in the general population. However, differences are seen within the White ethnic group: individuals in the Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group are significantly over-represented in both public and private law.

In both public and private law, Black, African, Caribbean or Black British children and adults, and those from Mixed or Multiple ethnic groups, are overrepresented, while Asian or Asian British children and adults are underrepresented.

There is limited data about the ethnicity of children and families who come into contact with the family justice system.

This data is not published by the Ministry of Justice or HMCTS. From 2016/17 Cafcass England began recording ethnicity data more systematically.

In 2020/21 ethnicity data was recorded for 93.8% of children in public law proceedings and 85.6% of children in private law proceedings.

Cafcass Cymru have recently begun recording ethnicity data, however these data are currently not sufficient quality for research on current or historical trends. Data linkage approaches have been used in Wales to explore the ethnicity of children and families in the family justice system.

In Wales, the largest proportion of children and adults in both public and private law cases are White (95%), which is equivalent to the proportion in the general population.

The proportion of individuals from Black, African, Caribbean or Black British, and Other ethnic groups in both public and private law cases also reflects the general population. This contrasts to the situation in England, where adults and children from Black, African, Caribbean or Black British or Other ethnic groups are overrepresented in public and private law proceedings.

Adults and children from Mixed or multiple ethnic groups are over-represented in both public and private law cases, while those in the Asian or Asian British group are under-represented.

Are certain minoritised ethnic groups over- or under-represented in private and public law cases?

Where do children live?

Public law

In public and private law, there is a clear link between area deprivation and rates of family court applications.

A regional picture of children in care

In public and private law, there is a clear link between area deprivation and rates of family court applications.

The geography of private law need is similar, with higher rates in Wales and the north of England, and the lowest rates in London and the South East.

Are children mentally and physically healthy?

Disability

In 2021, for the first time, Cafcass published data about the number of children with disabilities with whom they had worked in 2020/21. The data is not complete, it is recorded for 77% of children in the year 2022/23.

The data shows higher prevalence of children with autistic spectrum disorder in both public and private proceedings compared to all pupils.

A higher proportion of children in public and private law also had physical disabilities recorded compared to all pupils.

Equivalent data is not available for children in Wales.

Using linked administrative data in Wales, research has shown that children involved in public and private law proceedings in Wales are at increased risk of depression and anxiety, compared to similar children not involved with the family courts.

Children subject to care proceedings had twice the risk of depression and 20% higher risk of anxiety than the comparison group.

Children involved in private law proceedings had 60% higher risk of depression and 30% higher risk of anxiety.

Are parents mentally and physically healthy?

Linking family court data to health records in Wales has enabled researchers to better understand the health vulnerabilities of parents involved in proceedings.

Similar analysis has not yet been carried out in England.

Linking family court data to health records in Wales has enabled researchers to better understand the health vulnerabilities of parents involved in proceedings.

Similar analysis has not yet been carried out in England.

Using linked administrative data in Wales, research has identified the health vulnerabilities of mothers whose babies are subject to care proceedings in the first year of life.

Of these women, a very high proportion had significant prior mental health conditions at, or before, attending for antenatal care. In addition, around two-fifths (38%) of mothers were documented as having had a GP or hospital contact or admission relating to substance use prior to the child’s birth. Two thirds (63% and 60% respectively) were recorded as smokers at booking and at the time of birth.

This is not collected for children in private law cases.

How likely is it that mothers involved in proceedings have received care for mental health or substance use?

Linking family court data to health records in Wales has enabled researchers to better understand the health vulnerabilities of parents involved in proceedings.

Similar analysis has not yet been carried out in England.

Research has identified the increased health vulnerabilities of men and women involved in private family law applications in Wales.

This includes significantly higher prevalence of mental health conditions, self-harm, substance misuse and domestic violence compared to a comparison group of adults, matched according to age, gender and area-level deprivation.

Are adults involved in private law cases more or less likely to experience physical and mental health problems prior to court?

What are the family circumstances?

Income and debt levels

We know very little about the circumstances of families involved with the family justice system, including income, debt and housing.

Information about family and parental circumstances is, in most cases, collected by local and/or national agencies. However, this data is rarely linked to family court data.

These are important gaps. An understanding of family characteristics might allow us to identify better ways to support children and their families at an earlier stage, before they even reach family courts.

Most research to date has used information about the level of deprivation in the area where families live to make assumptions about individual family circumstances.

We know that children and adults involved in both public and private family law are more likely to be living in deprived areas.

Research from Wales has shown that families in public and private law proceedings have shorter average tenancies than families not involved in the FJS.

Research from Wales has shown that families in public and private law proceedings have shorter average tenancies than families not involved in the FJS.

We know very little about the circumstances of families involved with the family justice system, including income, debt and housing.

Information about family and parental circumstances is, in most cases, collected by local and/or national agencies. However, this data is rarely linked to family court data.

These are important gaps. An understanding of family characteristics might allow us to identify better ways to support children and their families at an earlier stage, before they even reach family courts.

In 2019/20, 29% of fathers and 31% of mothers involved in private law applications lived in areas in the most deprived quintile of England, with 52% of fathers and 54% of mothers living in the two most deprived quintiles.

A very similar pattern was found in Wales.

From April 2018 transitional protections were in in place, which continued during the roll out of Universal Credit. These protections mean that pupils eligible for free school meals on or after 1 April 2018 retain their free school meals eligibility, even if their circumstances change.

If a child was eligible for free school meals, they remain eligible until they finish their current phase of schooling (primary or secondary) in 2023.

The introduction of transitional protections is the main reason for the increase in the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals seen in recent years, as pupils continue to become eligible, but fewer pupils stop being eligible.

Are children in need or on a protection plan in England more likely to be eligible for free school meals?

Are children in need or on a protection plan in Wales more likely to be eligible for free school meals?

Who do children live with?

Parents

We know very little about the circumstances of families involved with the family justice system, including income, debt and housing.

Information about family and parental circumstances is, in most cases, collected by local and/or national agencies. However, this data is rarely linked to family court data.

These are important gaps. An understanding of family characteristics might allow us to identify better ways to support children and their families at an earlier stage, before they even reach family courts.

Children involved in public and private law proceedings in Wales are more likely to be living in lone-parent households than their peers. Around 10% of children in public law are living with grandparents.

What is the household composition of children involved in public and private law cases?

We know very little about the circumstances of families involved with the family justice system, including income, debt and housing.

Information about family and parental circumstances is, in most cases, collected by local and/or national agencies. However, this data is rarely linked to family court data.

These are important gaps. An understanding of family characteristics might allow us to identify better ways to support children and their families at an earlier stage, before they even reach family courts.

The majority of households have one or two children, but in public law, more families are living with 3+ children. We know the percentage of cases that involve siblings in England.

How many siblings do children involved in public and private law cases have?

Are parents receiving parenting and relationship support?

We are unable to judge the effectiveness of interventions as there is limited national data to show what support families may have received before, during, or after public or private law proceedings.

Are parents receiving support for drug and alcohol issues?

There is no national data showing how many parents of children in the family justice system have received help with addiction problems.

We are unable to judge the effectiveness of interventions as there is limited national data to show what support families may have received before, during, or after public or private law proceedings.

Are parents receiving mental health and emotional support?

We are unable to judge the effectiveness of interventions as there is limited national data to show what support families may have received before, during, or after public or private law proceedings.

Are parents receiving support with housing or debt problems?

We currently have no way to track whether support for housing, debt or other issues was given or accessed.

We are unable to judge the effectiveness of interventions as there is limited national data to show what support families may have received before, during, or after public or private law proceedings.

Are parents accessing mediation?

The Legal Aid Agency publishes figures on the number of publicly funded mediations for separating parents.

However, no national data is collected on privately funded mediations.

We are unable to judge the effectiveness of interventions as there is limited national data to show what support families may have received before, during, or after public or private law proceedings.

Data published by the HMCTS shows that the number of mediation starts and agreements has decreased significantly following LASPO in 2012/13.

In the last quarter (January to March 2023), Mediation, Information and Assessment Meetings decreased by 1% compared to the previous year and currently stand at around a third of pre-LASPO levels. Family mediation starts decreased by 14% and total outcomes decreased by 2%, of which 56% were successful agreements, and are now sitting at around half of pre-LASPO levels.

Domestic Abuse Perpetrator Programmes have been severely impacted by the pandemic. By May 2021, 700 families were affected by delays because of the lack of available programmes.

How common are publicly funded mediation assessments, mediation starts and successful agreements each year?

Number of children involved in applications

Wales

Cafcass Cymru publish data about the number of s.31 care applications they receive each year.They do not publish information about the number of children these applications concern.

Public care applications fell from 881 in 2020/21 to 729 in 2021/22

How many public care applications are made each year in Wales?

How many children are involved in private law applications in Wales each year?

Has the number of children involved in public care and private law cases changed over the past 10 years?

How are hearings being held?

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of family court hearings were moved online. Although social distancing measures have now ended, some hearings are still held remotely (telephone or video) or as ‘hybrid’ hearings (a mix of in-person and remote).

During the pandemic, HMCTS published some data on how hearings were being held. However, the data is no longer published.

How were hearings held during the COVID-19 pandemic?

How long do cases last?

Private law

Private law proceedings are also taking longer. In 2023, cases took an average of almost 46 weeks to reach final order. This is the longest duration in the time series.

How long do private law cases last?

Care proceedings are taking longer. This has been exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, 23% of cases were completed within the 26 week limit, compared to 31% in 2020.

Data for public law in 2022 is not available.

How long do public law cases last?

Do orders match what was sought?

In public law, the outcomes of applications are binary–an order is granted or refused.

In private law, the majority of applications are granted, but the critical factor is the content of the order.

This is currently unknown for private law on a national level.

In public law, for most order types, the number of orders is greater than the number of applications in each year. The exception is with care orders, where the number of applications far exceeds the number of orders.

Data on orders for 2022 is not available. Applications for Special Guardianship Orders in public law declined by over 60% from 183 in 2021 to 66 in 2022, while the number of applications for Supervision Orders grew from just over 1,500 in 2021 to almost 2,200 in 2022.

In public law, the outcomes of applications are more binary–an order is granted or refused.

In private law, the majority of applications are granted, but the critical factor is the content of the order.

This is currently unknown for private law on a national level.

While applications for Child Arrangement Orders (spends time with) declined by over 6% from 2021 to 2022, the number of orders granted fell by almost 12%. A larger decline in orders relative to applications was also seen in Child Arrangement Orders (lives with) with a very slight 1% decline in the number of applications from 2021 to 2022, compared to a 7.4% fall in orders granted.

In private law, the majority of applications are granted, but the critical factor is the content of the order. This is currently unknown for private law on a national level.

Have the number of private law applications changed over time?

Have the number of private law orders changed over time?

Have public law orders and private law applications changed over time?

Public law

According to a recent one-off analysis, children are more likely to be subject to care orders than any other order, however in recent years there has been a sharp increase in the use of special guardianship orders (SGOs). Over the same period the proportion of children placed for adoption has decreased.

Have orders made in public law proceedings changed over time?

What are families’ experiences?

How do we know whether justice is being served by a system that has such limited feedback from those affected by it?

Are people legally represented in court?

In 2023, in only 19% of cases disposed were both parties legally represented. The vast majority of cases therefore involve at least one party representing themselves, with 39% of cases having no parties represented.

Research has found that the majority of litigants in person experience fear and anxiety, confusion, marginalisation, and frustration with a slow, time-consuming court process.

Do people in private law proceedings have legal representation?

How do children participate in proceedings?

A child’s right to participate and have their voice heard in private law proceedings is acknowledged in legislation and guidance – both as a way of informing welfare-based decisions and upholding their rights.

There are several ways that children may be able to participate in proceedings – including through a section 7 report (either from Cafcass or the local authority), a section 37 report, a rule 16.4 appointment, children writing to or meeting with the judge, giving evidence, engaging with experts such as psychologists and independent social workers, and the use of child-friendly judgments.

Analysis of Cafcass England/Cafcass Cymru data has shown that, for cases that started in 2019/20, around half of the children – 53.9% in England and 47.5% in Wales – had at least one marker of participation within three years of the case start date. This means that for almost half of the 67,000 children in England and Wales who were involved in a private law case starting in 2019, there is no indication that they participated in their case.

In England, two-fifths of children aged 10 to 13 and a greater proportion of older teenagers had no indication that they had formally participated in proceedings. In Wales a similar pattern is seen. The level of participation was lowest for those who were the only child in their case in England and Wales.

Although the study was not able to capture all possible participation, this suggests that strikingly few children have a voice in proceedings.

What proportion of private law cases have evidence of child participation?

What are the ways in which children participate in private law cases?

How many children are deprived of their liberty?

The term ‘deprivation of liberty’ comes from Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which provides that everyone, of whatever age, has the right to liberty. A deprivation of liberty occurs when restrictions are placed on a child’s liberty beyond what would normally be expected for a child of the same age.

The family courts can authorise a deprivation of liberty under section 25 (s.25) of the Children Act 1989 (and section 119 (s.119) of the Social Services and Well-being Act (Wales) 2014), which places a looked-after child (age 10–17) in a registered secure children’s home, or via the inherent jurisdiction of the high court, which can be used when none of the other statutory mechanisms apply, and authorises the placement of a looked-after child in an alternative, unregulated secure placement.

In July 2022 the President of the Family Division launched the national deprivation of liberty court. Based at the Royal Courts of Justice, it deals with all new applications seeking authorisation to deprive children of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction and will run for a 12-month pilot phase finishing in June 2023. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory was invited to collect and publish data on these applications.

Since July 2022, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory have published monthly briefings highlighting high level data trends.

How common are deprivation of liberty applications?

In July 2022 the President of the Family Division launched the national deprivation of liberty court. Based at the Royal Courts of Justice, it deals with all new applications seeking authorisation to deprive children of their liberty under the inherent jurisdiction and will run for a 12-month pilot phase initially. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory was invited to collect and publish data on these applications.

Do cases return to the family justice system?

Private law

Recent analysis of data from England shows the overall level of return between 24% and 27% of private law applications between 2013/14 and 2019/20 were made by an applicant who had been involved in a previous application within the last three years.

In Wales, there is a similar pattern of recurrence. Around a third (31%–34%) of private law applications between 2014 and 2018 were made by an applicant who had been involved in a previous application within the last three years.

Around 4% of children in private law cases return to the family justice system via public law proceedings.

Between 2008 and 2016 return cases made up 6% of total public law demand.

Approximately one in four mothers involved in care proceedings return within seven years.

Are children doing well in school?

Standard at Key Stage 2 (England)

There is evidence of a stark attainment gap among looked-after children and children in need, compared to the general population.

DfE data also shows that looked-after children are almost four times more likely to have a special educational need (SEN) than all children. In 2023/24, over half (57%) of children in care have special educational needs, compared to 18% of all pupils.

We do not have comparable data for children involved in private law proceeding.

Percentage of students reaching expected standard at Key Stage 2, England, 2023/24

Attainment 8 measures the average achievement of pupils in up to 8 qualifications. Decreases in average attainment scores have fallen for all groups from 2020/21 to 2022/23 with the largest falls for children on a protection plan.

What are the average Attainment 8 scores of children in social care in England?

How do children in social care perform academically in Wales?

Percentage of students reaching expected standards at key stages, and Key Stage 4 percentage that achieved Level 2, Wales, 2019 (StatsWales 2020a)

Absences for almost all groups of children increased in 2021/22 compared to the previous year. For example the overall absence rate for all pupils increased from 4.7% in 2020/21 to 7.6% in 2021/22. Absences range from 7.6% on average for all pupils to a high of almost 20% for children on a protection plan. Children who had been looked after for more than 12 months had lower absences than those who had been looked after for less than 12 months, though the difference was smaller compared to the previous year.

Do children involved in social care get additional support at school?

Absences range from 4.7% on average for all pupils to a high of almost 15% for children on a protection plan. Children who had been looked after for more than 12 months had lower absences than those who had been looked after for less than 12 months – 5.1% compared to 13.4%

Do children come into contact with the youth justice system?

In England, information on offending rates is collected for children aged 10 years or over – 40,990 children in 2025. Of these, the proportion convicted or subject to youth cautions or youth conditional cautions during 2025 was 2%, which has stayed steady for the past 4 years. In 2025 this equates to 800 children. Percentages were slightly higher Wales in 2023.

Males are more likely to offend than females – 3% of males were convicted or subject to youth cautions or youth conditional cautions during the year compared to 1% of females – a similar pattern to previous years.

Convicted or youth cautions for children in care in England & Wales

Convicted or youth cautions, children aged 10–17, England & Wales

Do children stay in education, employment and training?

We have data for England on the activity of care leavers. The proportion of formerly looked-after children that are not in education, employment or training (NEET) aged 19-21 has been around 40% for the past five years, though did fall slightly in 2022 to 38%. In 2025, the proportion of 19-21 year old care leavers in education is 27% and those in employment or training is 27%. Up-to-date Welsh data, and data for private law, is currently unavailable.

How many care leavers are engaged in higher education, training or employment?

What are children’s health outcomes?

Up-to-date health checks

There have been slight declines in the percentages of CLA with up to date immunisations and health assessments, though both measures stand at 85% in England. The % of CLA with up to date dental checks has started to recover from its sharp fall during the pandemic, though has not returned its pre-pandemic levels. In Wales, the decline in the % of CLA with up to date dental checks was less pronounced, at 60% compared to a low of 40% in England.

Do children in care in England and Wales have up to date health checks and immunisations?

Health outcomes for looked after children, England and Wales 2016/17-2024/25

In 2024/25, 3% of looked after children in England were identified as having a substance misuse problem, compared to 8% in Wales in 2022/23.

We do not have comparable data for children involved in private law proceedings.

Proportion of looked after children identified as having a substance misuse problem, England and Wales, per year

Substance misuse is defined as ‘intoxication by (or regular excessive consumption or and/or dependence on) psychoactive substances, leading to social, psychological, physical or legal problems’. It includes problematic use of both legal and illegal drugs (including alcohol when used in combination with other substances). ‘Substance’ refers to both drugs and alcohol but not tobacco. Interventions may include advice, guidance or therapeutic support.

In England, we know the number and proportion of children who have socio-emotional issues that are a ‘cause for concern’ as identified by the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). In 2024/5, a SDQ score was reported for 78% of looked after children in England aged 5 to 16 years.

The emotional and behavioural health of children in care in England

Where are children living?

England

The proportion of looked after children starting in foster care fell slightly in 2024/25 from 55,960 to 54,820. More children have been placed in secure units, children’s homes and semi-independent living (although much of the increase here is in semi-independent living). Fewer children have been placed with parents and adoption placements have also fallen compared to the previous year.

What type of placements are used for children in care in England?

Children looked after at 31 March by placement type, per year in England

What type of placements are used for children in care in Wales?

Children looked after at 31 March by local authority and placement type, per year

Do children form good relationships?

Having supportive, strong and healthy relationships is vital for children’s development and mental wellbeing. But information about children’s relationships is not measured by the system.