“We just roll our sleeves up and deal with things.”

Helen Scourfield is not one to shy away from an issue. The barrister and former chair of the Cleveland and South Durham Local Family Justice Board has a pragmatic approach to problem-solving – an attitude that is shared across its membership.

The board is often held up as having a positive culture of collaboration and trust, despite some of the challenges that it faces. It covers cases involving children from the borough councils of Redcar and Cleveland, Middlesbrough, Stockton-on-Tees, Hartlepool, Darlington and the southern half of Durham county council, which all feed into the family court at Middlesborough.

“We are from a really deprived area with high levels of poverty,” says Alistair Nixon, a solicitor at Cygnet Law, who took over from Helen earlier this year. “We have high levels of knife crime and crime generally – there are some huge issues.”

So how did this particular board develop such constructive working relationships, and what can be learnt to help replicate its success in tackling local issues arising within the family justice system?

We just roll our sleeves up and deal with things.Helen Scourfield, Barrister

How the LFJB operates

Local family justice boards (LFJBs) were set up to help deliver improvements in family justice at a local level, but there is a wide range in how they are organised and operate. A “deep dive” into LFJBs last year by an independent assessor, Mutual Ventures, identified that Cleveland and South Durham had strong, collaborative leadership and that everyone within the system was working towards a shared goal.

“The local family justice board has provided a helpful forum for us to try and resolve issues of practice that are coming up on case after case after case, to try to create a solution,” says Alistair. “It’s a forum to take a step outside of the day-to-day matters, and look at if there is perhaps a more strategic way that it can be approached.”

The board meets quarterly, and have sub-groups that meet monthly. It has representatives from each of the local authorities, Cafcass, a regional adoption agency, senior social workers and lawyers, police, and the Designated Family Judge (DFJ), who attends as an observer.

Mr Nixon says that regular attendance from a wide range of participants is vital. “We’ve got active attendance from relevant people and we address national issues and the more discrete issues that arise locally. One is the quest to establish an FDAC locally, which is really high on the agenda at the moment,” he says.

It’s a forum to take a step outside of the day-to-day matters, and look at if there is perhaps a more strategic way that it can be approached.Alistair Nixon, Cygnet Law

The culture at Cleveland and South Durham

Alisha Lynas has been a member of the board in two different roles, originally as the service manager for Cafcass at Teesside and in her current role as the head of service of care planning for Darlington Borough Council.

She describes the culture of the board as “all being in it together”, which is key to enabling challenging conversations. “We are able to talk about where there are difficulties with the judiciary, with partners from other local authorities, with private solicitors, to really look at things that need to change,” she says.

Alistair agrees. “People always attend it in a very constructive fashion,” he says. “It’s a very collaborative forum, and I think perhaps it’s something that comes out of everyone confronting difficult issues together.”

He gives an example of a shortage of foster placements, which is an issue in Cleveland and South Durham as it is across the country. “Local justice boards and courts and local authorities can’t create more foster placements, that’s out of their hands, but can we try to reduce the burdens on practitioners and improve the decision making, to help us navigate the problem,” he says.

People always attend it in a very constructive fashion. It’s a very collaborative forum, and I think perhaps it’s something that comes out of everyone confronting difficult issues together.Alistair Nixon, Cygnet Law

How did this culture evolve?

But it has not always been this way. Helen says that initially the LFJB was not particularly active.

“Practitioners generally – including myself – didn’t really understand its function or what it was there to do,” she says. She made it a priority to increase the visibility of the board amongst the different professions, and also organised social events to help everyone get to know each other.

She believes that former DFJ Her Honour Judge Gillian Matthews KC, who was succeeded by His Honour Judge Harvey Murray earlier this year,played a large part in setting the tone for the board. “She is such an inspiration. She has always been a really formidable, strong, natural leader. In the context of the Local Family Justice Board, she naturally, quietly, inspires people to want to affect change,” says Helen.

Mr Nixon says that there the board has a real focus on “cutting through the issues”, which he puts down to the pragmatic attitude of the individuals who attend. He also feels benefit from him being a lawyer who represents both local authorities and other parties. “As someone who sees it from different angles, I’m acutely conscious of the burdens on local authorities and the processes within them, and I think that is quite a useful thing to have,” he says.

This is borne out by Alisha’s experience. “What I’m always impressed by is how it’s aimed at all practitioners across the board, whether it be social workers or lawyers. I think that makes difference. It feels like it’s for everybody involved in social care,” she says.

Attending national conferences and events as chair of the LFJB made Helen aware that other boards did not always operate with the same willingness to tackle issues collaboratively.

“From my perspective, we don’t allow our LFJB to become a negative moaning platform. We have to be constructive, people have to feel inspired to try to help with the change,” she says.

That doesn’t mean that the board does not want to hear about problems that arise. Helen says she would actively seek out issues, so that they could be resolved swiftly and, where necessary, in confidence. She gives the example of complaints that arose due to the lack of separate rooms at the busy court centre at Teesside, which meant that private conversations were being carried out in public areas.

“You could have ten sets of four or five people all talking about their case, and people overheard other people criticising them. It upset them and then they didn’t want to go to court because they were anxious,” she says. “So I just dealt with it. I’m emailed around to everybody to say this has happened. People can overhear what other people are saying: we need to mindful and we all need to be nice to each other.”

Working practices

This culture has enabled improvements in working practices. The board have organised themselves to help disseminate information and guidance amongst the different practitioners, to prevent duplication and to help delegate and share workloads. Wellbeing is also a top priority, with breathing and relaxation exercises as part of the agenda of their annual conference.

“The judges got really into it,” says Helen, laughing. “It was a bit daft. But we’re all fried. A lot of us work 16 hour days. We need to be firing on all cylinders, otherwise we’re not any good at doing the job.

“At Teesside, we actively look after each other’s wellbeing. People know when other people are not right. And it’s a nice feeling, knowing you’ve got support.”

Impacts for children

These improvements in how the board operates has translated directly into better outcomes for children. The board display a curiosity when issues are presented, and a genuine desire to investigate and resolve them.

“One of the reasons why we end up being an outlier is because of the demographic of our families who really struggle,” explains Alisha. “But we really interrogate issues that come up. So we don’t just go: ‘Oh, because it’s a difficult area’. We go: ‘Right. Let’s understand that.’”

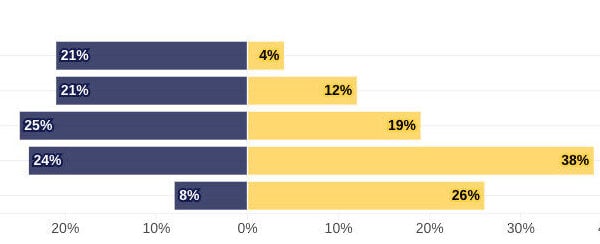

She gives the example of recent statistics which showed that Teesside had very high rates of care orders at home. The LFJB were quick to investigate. Alisha says: “We were a real outlier nationally. We did a deep dive piece of work involving Cafcass and all the local authorities within the LFJB to understand what was driving that. It had all of us together in a united front, as something that bothers us all, that this isn’t right for our children. It had a massive impact. We saw that start to decline and practice change as a result of it.”

One of the reasons why we end up being an outlier is because of the demographic of our families who really struggle, but we really interrogate issues that come up. So we don’t just go: ‘Oh, because it’s a difficult area’. We go: ‘Right. Let’s understand that.’Alisha Lynas, Darlington Borough Council

Creating a constructive culture

Helen believes that establishing these practices is not complicated. “I suspect that a lot of people in a lot of DFJ areas don’t even know that an LFJB exists,” she says. She suggests starting with the basics: a short video call setting out what the LFJB does and how it works.

“It really is as simple as good communication, making yourself visible, explaining the role of the LFJB to people,” she says. “You don’t have to come up with the most brain-busting idea. You can have really simple mechanisms that make things much easier for everybody. Like: if you have an issue about this, this is who you contact. Or doing an email round saying, ‘We’ve got a meeting next month, if anyone has anything they want to raise, feel free to get in touch with me. No question is going to be deemed a stupid question.’ And that opens up a whole different ethos.”

It may be simple, but she adds a caveat: “it is hard work”. “We don’t just sit talking about whether we can get more conference space, we talk about actual changes that will have an impact on the lives of the children subjects in the proceedings,” she says.

Ultimately, it is children within the family justice system who benefit from different practitioners working well together through the LFJB. Helen says that this focus is set by the example of Judge Matthews. “She absolutely wants to get this right for the children in the system,” she says. “And that’s what drives us all.”

She absolutely wants to get this right for the children in the system, and that’s what drives us all.Helen Scourfield, Barrister