Acknowledgements

The research team wish to express their thanks to Rob Street and Ash Patel, Nuffield Foundation for their valuable comments.

We would also like to thank Teresa Williams and Tracey Budd, formerly of the Nuffield Foundation, for their support and guidance throughout the project.

We would also like to thank colleagues at Cafcass: Anthony Douglas CBE, Richard Green, Helen Johnston, Emily Halliday (formerly Cafcass), Liz Thomas, Claire Evans and Jigna Patel.

We thank Sir James Munby (formerly President of the Family Division) for his support and interest in the project and HHJ Clive Heaton (Judicial College) for his assistance.

We would like to extend special thanks to members of the Advisory Group for their guidance and advice throughout the project: Mary Ryan (RyanTunnardBrown) (Chair of the Advisory Group); Noel Arnold (Association of Lawyers for Children); Alexy Buck (Ministry of Justice); Ross Campbell (Department for Education); Martha Cover (Association of Lawyers for Children); Rachel Dubourg (Ministry of Justice); Dr Lisa Holmes (Rees Centre, University of Oxford); Professor Joan Hunt OBE (Cardiff University); Helen Johnston (Cafcass) and Emily Halliday; HHJ Peter Nathan (Designated Family Judge); Professor Julie Selwyn CBE (University of Bristol); John Simmonds OBE (CoramBAAF); Professor Fiona Steele (LSE); Amy Summerfield (Ministry of Justice); Jim Wade, Honorary Research Fellow (University of York).

We warmly thank the local authorities for their ongoing support and assistance with this project. They could not have been more helpful to us.

We also want to pay special thanks to Grandparents Plus. Elements of the study would not have been possible without their invaluable support and advice.

We also gratefully acknowledge the assistance from Family Rights Group.

We also wish to thank the parents, special guardians and professionals who generously shared their views and experiences with us, greatly enriching the findings of this study and our understanding of the issues.

Finally, we would like to express our warm thanks to the following people for helping us collect the information from local authority files: Louise Fusco, Lisa Morriss, Sheila Harvey, Sandra Latter, Jade Ward and data collectors employed by the participating local authorities.

Introduction and background

This report is about the use of ‘family orders’ to support family reunification and placement with family and friends as outcomes of S31 care and supervision proceedings brought under the Children Act 1989 1. These proceedings are brought by local authorities for children who they believe have experienced, or are likely to experience ‘significant harm’ as a result of the parenting they have received falling below a reasonable standard. They are amongst the most vulnerable children in society who have met the highest threshold of concern, and their futures cannot be decided without the intervention of the court.

The main focus is on supervision orders made by the courts to help support birth families to stay together, and on special guardianship when the child is placed with family and friends, with or without a supervision order. It is important to distinguish between these two family orders regarding the support they provide for permanency. A special guardianship order (SGO) lasts until the child reaches the age of 18, but a supervision order is time-limited. A supervision order places a duty upon the local authority to ‘advise, assist and befriend the supervised child’ 2. It is initially made for a period up to one year, but can be extended after this to a maximum of three years. A special guardianship order gives the carers the main responsibility for the child’s care and upbringing but retains the legal link with the birth family. The local authority does not hold parental responsibility when either order is made.

The over-arching aim of this study was to understand the opportunities, challenges and outcomes of these orders, and their use at national and regional level. This is the first study of both supervision orders and special guardianship to make use of national (England) population-level data routinely produced by the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) concerning all children subject to S31 care and supervision proceedings. It is also the first study to use this data to examine the proportion of special guardianship orders in which a supervision order is also made for the child.

The report is being published at a critical time in family justice. The overall trend regarding care demand is upward. Despite a small drop in demand in 2017/18, the number of children in care and supervision applications is still more than double the figure recorded in 2007/08 3. This has created huge pressures on the family courts and children’s services alike. As part of the inquiry into ways of tackling the issues, the recent Care Crisis Review 4 concluded that the family itself is an underused resource. Since 2013, case law has also affirmed the important role of the courts and children’s services in promoting permanency orders that keep families together 5, and most recently called for new guidance on special guardianship 6 . This comes just three years after a major review undertaken by the Department for Education 7 (DfE) introduced changes to the regulatory framework. At the same time however, there remains concern about the quality and timeliness of assessment of potential special guardians, particularly in the context of the statutory requirement introduced in the Children and Families Act 2014 8 to complete S31 proceedings within 26 weeks, save for exceptional circumstances. These concerns take place in the context of a small number of high profile serious case reviews following the deaths of children on special guardianship orders. Moreover, in 2017 a serious case review in Derbyshire called into question the value of the supervision order 9, echoing views as early as 1999 that the supervision order may not be “worth the paper it is written on” 10. Finally, the Children and Social Work Act 2017 11 has raised expectations about the requirements of permanent placements in all family orders to take account of children’s long-term needs in the light of their histories of vulnerability. In short, expectations have risen as resources have decreased to deal with rising demand.

For all these reasons, it is essential to understand the extent to which these family orders provide safe and sustainable family-based alternatives to public care, and to understand more about local authority and court decision-making, as well as family experiences.

Study objectives

The objectives of the study were:

- a. To use administrative data held by Cafcass to provide the first national (England) analysis ofsupervision orders and special guardianship, ascertain their use over time and by region, and their risk of breakdown, evidenced by children returning to court for further S31 proceedings.

- b. Through intensive case file review of children placed on supervision orders and special guardianship orders in four local authorities, to describe:

- the profiles of the children and their parents/primary carers

- the reasons why children were returned home or placed with special guardians

- the frequencies of further neglect or abuse, permanent placement change, or return to court over the follow-up

- how the court and local authority carried out their duties

- compare the features and outcomes of special guardianship cases with or without anattached supervision order.

- c. Through focus groups with family justice professionals, to obtain their views on what isworking well and what is not working well in relation to supervision orders and special guardianship, and their recommendations regarding the need for legal, regulatory, policy and practice change.

- d. Through interviews and focus groups, to understand the experiences and chart the recommendations of:

- parents reunited with children who were placed on a supervision order

- special guardians.

- e. To consider whether there is a need to strengthen the robustness of supervision orders and special guardianship, and identify any policy and practice recommendations arising from the findings.

Methods

A mixed methods study 12 was carried out between 2015 and 2018 using both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Profiling supervision orders and special guardianship orders using national level data

National (England) population-level data held by Cafcass was used to identify the use and outcomes of supervision orders and special guardianship orders over time, based on all usable records from 2007/08 to 2016/17. From this dataset, the pattern of final legal orders was examined using records between 2010/11 to 2016/17 13.

Cafcass has only recently started to collect placement data, hence the final legal order was used as a proxy indicator of final planned permanency arrangements for the child. This is the most reasonable assumption that can be made, on the basis of the information that was available to the research team, at the time of this study 14. Six legal order types were identified to compare the use of supervision orders and special guardianship as a legal outcome of S31 proceedings (see table 1). Applications for special guardianship, residence orders, and child arrangement orders that were not formally linked to significant harm through S31 proceedings were excluded from this study.

Analytic category (devised by research team) proxy indicator of permanent placement type | Legal order (as recorded by Cafcass) |

With parents | Order of no order (ONO)15 |

With parents | Supervision order (SO) |

With family or friends | • Residence order/Child arrangements order (live with) (RO/CAO live with) • Special guardianship order (SGO) |

With foster carers | Care order (CO) |

Placed for adoption | Placement order (PO) |

To provide estimations of the probability of children returning to court for further S31 proceedings after a supervision order or special guardianship order had been made, survival analysis 16 (time to event analysis) was used. Survival analysis is a statistical method that is used when cases are followed up for variable lengths of time and the analysis must adjust for this. In this study, the time to the first occurrence of the event of interest (return to court) was tracked.

Using case files to deepen understanding of supervision orders and special guardianship

An intensive descriptive case file study of children subject to supervision orders and special guardianship in four local authorities (two in the North of England and two in the South) was completed.

The samples comprised:

- [A] Supervision orders: information was collected on 268 (73%) of the 367 children placed onsupervision orders or on supervision and residence/child arrangement orders in the four local authorities covering the period 2013/2014 and 2014/2015. We were unable to collect data on the other 27% of the children because parents withheld consent, access to files was restricted, or the files were not available. The sample was then divided into two sub-samples on the basis of the placements:

-

- [Ai] Supervision order reunification: 210 children from 127 families placed on a supervisionorder in 2013/14 and 2014/15 and reunited with at least one of the parents they had lived with before the proceedings started. The children were tracked for up to four years after the S31 proceedings ended.

- [Aii] Supervision order and residence order/child arrangements orders (live with): 58 children who had moved to a new primary carer that they had not lived with previously. Due to small numbers we have only included this sub-sample in the appendix to the main report.

- [B] Special guardianship orders: out of 112 children subject to special guardianship orders in 2014/2015 in the four partner local authorities we were able to collect data on 107 children, which represents 96% of the total possible sample of children. For five children, access to case files was restricted or not available. Cases were tracked for three years after the S31 proceedings ended.The sample was sub-divided into two sub-samples:

- [Bi] Special guardianship orders only: 57 children from 40 families.

- [Bii] Special guardianship orders with attached supervision orders: 50 children from 35families.

Data sources

Data sources were the local authority electronic records held by children’s services and the local authority legal bundles. The Cafcass electronic administrative database was used for matching the cases with the local authority records.

Data analysis

The quantitative analyses undertaken for the national and case file studies comprised descriptive statistics, and survival analysis was used for calculating the probability of events such as recurrence of neglect, permanent placement change or return to court. Survival analysis was based on the first time each of these three events occurred in the follow-up period. Recurrence of neglect and abuse was identified from the case files using the 2015 NSPCC Neglect Appraisal tool (Hodson, 2015) 17.

Interviews and focus groups

- a. Interviews were held with five birth parents 18.

- b. 13 focus groups were held with family justice stakeholders (n=89 participants) recruited through the local authorities and the Judicial College, of which:

- nine were held with social workers, senior managers, local authority lawyers and Independent Reviewing Officers (IROs). A total of 66 people took part 19 and the focus groups were held in each of the four local authorities.

- two were held with Cafcass officers (n= 13). One was held in the North of England andone in London.

- two were held with members of the judiciary at the Judicial College (n=10).

- c. Seven interviews and three focus groups were held with special guardians (n=24) recruited from the participating local authorities and a leading voluntary organisation. The sample came from the North and South of England.

All interviews and focus groups were analysed thematically using NVivo.

The study had ethical approval from Brunel University London and Lancaster University, Cafcass and the four local authorities. The study transferred to Lancaster University in 2016. The research team worked with pseudo-anonymised records 20 to preserve the privacy of the children and families in the national and local authority data. All data was anonymised in respect of interviewees and members of the focus groups. Parents and special guardians received a voucher of £20 in recognition of the time they had given to participate in the study. The study also had approval from the President of the Family Division, the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS), and the Department of Education.

Study challenges and limitations

The study faced a number of challenges and limitations. Children who return home on a supervision order have no direct equivalents, so it was not possible to address the question of the impact of a supervision order by means of a comparison study. This means that we are not able to establish any causal relationships between the making of a supervision order and child outcomes. The samples for the case file studies were small and this reduced our ability to undertake some quantitative analyses on possible inter-relationships between particular measures. The study relies heavily on administrative data and case files collected for case management purposes and not for research. Hence, the range of questions we have been able to address has been limited by the scope and quality of that data. The small number of parent interviews means that the findings must be treated as indicative only but they provide valuable insights. Provided that all these points are borne in mind the study has yielded some important findings.

Main findings

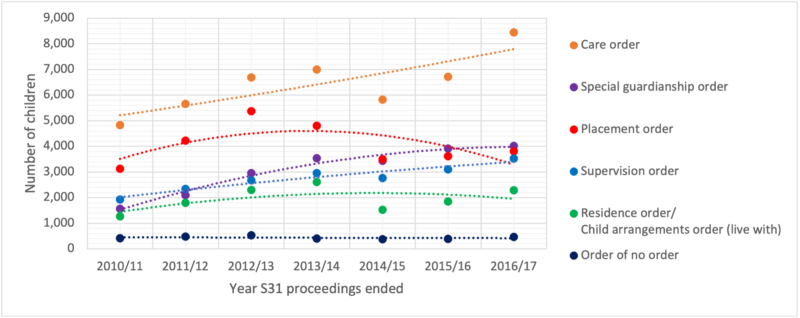

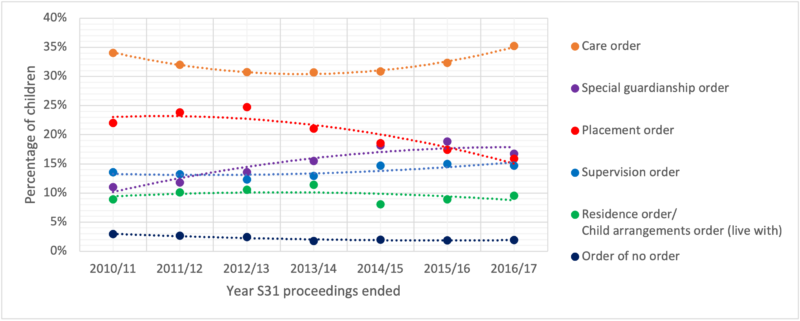

The analysis was based on a total of 175,280 individual children’s records, drawn from 101,759 cases of S31 proceedings that started between 2007/08 and 2016/17 21. The analysis of legal outcomes (see Table 1) was possible for 140,059 children in 81,758 cases that concluded between 2010/11 and 2016/17. All results are statistically significant unless stated otherwise.

There has been a major increase in the number of children subject to S31 proceedings over time. The number of children has risen from 11,319 in 2007/08 to 25,092 in 2016/2017.

Between 2007/08 and 2016/17, only 6% of children subject to S31 proceedings had an application for a supervision order 22.

However, far more supervision orders were made at the conclusion of proceedings, than were applied for. Of all orders made at the conclusion of proceedings between 2010/11 and 2016/17, 14% were standalone supervision orders, 6% were supervision orders that were attached to residence orders/child arrangement orders (live with), and 5% were attached to special guardianship orders. Most supervision orders resulted from care applications rather than supervision applications. Between 2010/11 and 2016/17, 88% of all supervision orders made to support family reunification resulted from a care application.

Although the numbers of standalone supervision orders supporting family reunification have risen from 1,921 in 2010/11 to 3,528 in 2016/17, there has only been a small increase in their proportional use (from 14% in 2010/11 to 15% in 2016/17) due to the general increase in all S31 proceedings.

In contrast, there has been a marked rise in the use of special guardianship orders as a legal outcome of S31 proceedings, which increased from 1,566 (11%) to 4,018 (17%) during the same period. The proportion of children subject to placement orders fell from 22% to 16% during that time, despite the increase in the number of these orders from 3,125 in 2010/11 to 3,806 in 2016/17.

Only 1% of the children subject to special guardianship orders had an application for this order in their S31 proceedings, while 57% of the children subject to placement orders had an application for that order in the proceedings. This is important because it shows that the majority of special guardianship orders in the context of S31 proceedings are made by the court acting of its own motion rather than upon the application of a prospective special guardian.

There are marked regional disparities in the use of supervision orders. Over time, the North West court circuit has generally made less use of supervision orders than the five other court circuits. These variations were also demonstrated across the 40 Designated Family Judge (DFJ) areas in England.

Children on a standalone supervision order have the highest (20%) probability of a return to court for new S31 proceedings within five years compared to the five other types of order. Children who were aged less than five years old when placed on a supervision order are significantly more likely to return to court for new S31 proceedings than older children.

Children on a standalone special guardianship order have a 5% probability of new S31 proceedings within five years of the order being made. In contrast to children on standalone supervision orders, it is the older children who were more likely to return to court than those aged under five years old.

The trend of attaching a supervision order to a special guardianship order peaked at 35% of all special guardianship orders made in 2013/14, and despite a small drop to 30% in 2016/17, remains substantially above 2010/11 levels (18%). A supervision order attached to a special guardianship order increases the likelihood of new S31 proceedings within five years from 5% to 7%.

Children placed on a residence order/child arrangements order are more likely to have an attached supervision order than a standalone residence/child arrangements order. The risk of new S31 proceedings when a supervision order is attached approximately doubles over five years to 13% compared to 7% for children on a standalone residence order/child arrangements order.

Since 2014/15 the likelihood of ‘family order’ cases returning to court for new S31 proceedings has accelerated. Cases that concluded with a supervision order, a special guardianship order, or child arrangements order all had a higher probability of returning to court within two years for new S31 proceedings than cases that were concluded before that date.

Figure 1: Number of children subject to each of the six legal orders per year

Figure 2: Percentage of children subject to each of the six legal orders per year

The case file studies

Supervision orders supporting family reunification

The sample: 210 children and 175 adults from 127 families in four local authorities. 194 children were followed for up to four years after the supervision order was made.

The overwhelming majority of children (97%) were suffering from significant harm at the point the case was brought to court. Neglect (76%) and emotional abuse (65%) were most frequent, while physical abuse (44%) was more prevalent than sexual abuse (9%). The parents had extensive previous involvement with children’s services; 18% had been looked after as a child, 27% were known to children’s services during childhood, and 23% had had at least one child previously removed via care proceedings. These experiences are similar to those for a cohort of children who became looked after in Scotland in 2012-13 23.

Children’s exposure to domestic violence (56%), parental mental health problems (46%) and substance misuse (alcohol 30% and drugs 33%) were the main triggers to the court case. Relationship difficulties (57%) and non-engagement with services (67%) were the most frequent additional parental problems to which children were exposed.

The main reason for the supervision order was to continue to support the improvement made by parents during the S31 proceedings, following the return of their children. However, the order was also used for monitoring risk.

Based on tracking 194 children during the course of the supervision order and for up to four years beyond, a minority of the children (6%) had a permanent placement change or further S31 proceedings. However, 24% experienced neglect or abuse 24. Neglect (18%) predominated and was most frequent amongst children aged one to four years.

Case complexity was significantly associated with the risk of abuse and neglect during the supervision order. The more parental problems 25 the child was exposed to, the higher the probability of recurrence of abuse and neglect. Domestic violence, substance misuse, material difficulties and non-engagement with services were particularly likely to significantly increase risk. However parental mental health difficulties, physical health problems or disability showed no statistically significant association. It is important to note that the majority of the cases did not involve multiple problems, indeed 60% of the children were exposed to only 0-2 parental difficulties.

Children with emotional and behavioural difficulties (26%) or school attendance concerns (9%) were also at significantly increased risk of abuse or neglect during the supervision order. The following variables were not associated with heightened risk: developmental delay, learning difficulties, special educational needs, physical health problems, or the child’s age.

By the end of the follow-up, four years after the S31 proceedings concluded, there was some increase in the proportion of children who had either experienced abuse or neglect, a permanent placement change, or had returned to court for fresh S31 proceedings. Specifically, 40% had experienced further neglect, 24% had experienced a permanent placement change and 28% had experienced further S31 proceedings 26. 32% had emotional and behavioural difficulties.

By this point, 56% of the children had been exposed to parental housing difficulties and 49% to their financial difficulties. A higher proportion of children were affected by housing and financial difficulties by the end of the follow-up than when the S31 proceedings were issued. Of all the difficulties that the children experienced, it is important to note that housing and financial difficulties affected the greatest proportion over the follow-up.

During the course of the supervision order and the follow-up period, the majority of children were dealt with as children in need 27 cases, including when abuse or neglect recurred.

Based on 154 children whose records provided sufficient detail, frequency of social work visiting varied during the course of the supervision order; nearly half (47%) of the children received between nine and 12 visits by their social worker, 22% received between five and eight visits and 28% received over 12 visits. All children who had been neglected or abused were visited by their social worker at least nine times and many more than 13 times. Further information was collected on a sub-sample of 87 children, and there was considerable variability in the frequency of children in need reviews, with the views of the parents and children rarely emerging. It was difficult to establish frequency and patterns of service attendance or engagement from case file records. This in turn made it difficult to establish how far the potential supportive function of the supervision orders was being realised in practice.

Special guardianship orders supporting placement with family and friends

The sample: 107 children, from 75 birth families, placed with 77 special guardian families.

Special guardianship placements were very positive for the large majority of the children.

By the end of the three-year follow-up after the special guardianship order was made:

- 6% of the children had experienced neglect.

- 4% of the children had further S31 proceedings and 10% had further permanent placementchanges.

Where ongoing difficulties were reported, these related to:

- Housing and financial pressures faced by the special guardians.

- Tensions between special guardians and birth parents regarding contact.The majority of the special guardians were family or friends, and 81% were known to the child at the start of proceedings. None were previous unrelated foster carers.

The timing of the child’s move to live with the special guardian varied:

- 27% (N=29) moved before the start of the proceedings.

- 42% (N=45) moved during the proceedings.

- 31% (N =33) moved after the proceedings ended (the overwhelming majority within three months of the final order). These children had not lived with the prospective guardians to test the suitability of the placement before the order was made.

There was a North/South divide in the use of supervision orders attached to special guardianship. Children living in the Northern local authorities were significantly more likely to be subject to a special guardianship order with an attached supervision order than in the London authorities. 70% of the children in the North had both orders and 30% had a special guardianship order only. Only 30% of the children living in London had both orders and 70% had a standalone special guardianship order.

Over the three-year follow-up, the likelihood of placement breakdown and return to court did not differ significantly between the sample of children on standalone special guardianship orders and those with an attached supervision order. The estimated rate of emotional and behavioural difficulties was also similar, affecting 30% of the children 28.

Only 37% of children had a family group conference during proceedings. This was significantly more frequent when a supervision order was attached to the special guardianship order.

Professional perspectives on supervision orders and special guardianship

Sample: 13 focus groups with social workers, local authority lawyers, Independent Reviewing Officers (IROs), Cafcass, and members of the judiciary held in the North and London.

Professional views on supervision orders supporting family reunification

Some professionals found it confusing and illogical to have identical grounds for supervision and care orders, despite their very different implications. This may help explain why we found that very few local authorities applied for supervision orders in our national data, rather the majority of orders resulted from care proceedings.

Cases deemed suitable for the making of a supervision order were those that met the threshold criteria of significant harm to the child and where there was an established working relationship with the local authority, with positive parental engagement and progress demonstrated during the proceedings. In practice, however, one type of case, chronic neglect as opposed to immediate harm, was sometimes mentioned to steer the decision towards a supervision order rather than a care order.

Following the making of a supervision order, there were mixed views on the value of the order to support family reunification. A widespread view was that in principle, this legal option provided the local authority with an opportunity to provide further support to enable real change in parenting capacity.

Some professionals felt that a one-year supervision order was simply too short to bring about lasting recovery from longstanding serious psychosocial problems. It is noteworthy that very few professionals considered the possibility of a further application to court to extend the order. When asked about this option, social workers in particular said it would be difficult to get the courts to agree an extension either because the concerns remained unchanged or there was no immediate risk of harm. A main concern is that the supervision order does not of itself provide a quicker route back to court and that proceedings still have to be re-issued from scratch. From our analysis of Cafcass national records, we found very few applications for supervision order extensions, which confirms this finding of a reluctance to issue applications for an extension to the supervision order 29.

Many professionals also stated that the supervision order “lacks teeth” and needs to be strengthened. Professionals said that because the local authority holds no parental responsibility when a child is subject to a supervision order, this limits the leverage that comes with a supervision order. Moreover, there is no explicit duty in the legislation to monitor, only to ‘advise, assist and befriend’. This is seen to be a particular problem in cases where it is difficult to distinguish between genuine engagement and what was termed as “disguised compliance” during the supervision order. This point resonates with conclusions drawn by Lady Justice Bracewell 30 that any contract that the local authority draws up with parents is not enforceable. Similarly any conditions the court imposes are not enforceable 31, a finding that may help explain why courts very rarely imposed conditions on parents in the case file study. In this context, it is difficult to ascertain how simply lengthening the supervision order would address these limitations.

However, it is equally true that the supervision order does bind the local authority to provide at least some services that might otherwise not be made available, should the child be returned home on no order. Again, however, professionals were concerned that the child in need framework, under which supervision orders cases are managed, was not considered to offer children any special service and support entitlements beyond those received by other children in need which in the context of cut backs in service, can be minimal. Thus, some professionals felt that the supervision order was a “half-way house that takes nobody anywhere”.

Despite these reservations, professionals wanted to see the supervision order retained. When asked if time-limited care orders at home were potentially a better alternative, there was no support for introducing this option. Professionals suggested the following ways forward:

- Court directions could be used more frequently to strengthen the mandate on local authorities to provide more consistent help tailored to need – but the existing legal framework would need to be revised to allow this.

- Children placed on a supervision order should be dealt with as child protection cases rather than as children in need, which would strengthen oversight. Otherwise, consideration should be given to involving an IRO to oversee the child in need review process.

Overall, the sense from professionals is of an order, which in its current form is insufficient as a legal option for supporting safe and effective reunification. The original conception of this option as an effective alternative to a care order has not been realised in practice, which may explain why there has been little change in the proportionate use of this order over time.

Professional views on special guardianship

Professionals compared the assessment processes and support for special guardians with those for adopters. A consistent message was that special guardians have a tougher task than adopters as they have to manage contact with birth parents, often involving complex family dynamics that complicate the parenting task. However, whereas adopters receive preparation, a lengthier assessment, and information on the child including a health assessment, there is no such requirement for special guardianship. For these reasons, in the view of professionals, special guardians are treated less favourably at all stages of the assessment process.

Professionals consistently expressed concern about the rigour of assessments of prospective special guardians. In particular, they considered that the 26-week statutory timeframe has resulted in rushed assessments and in some cases, premature decisions on the suitability of the special guardian. They felt that with more time, they could undertake assessments that were both more thorough but also more sensitive to the experience of the special guardians. Varied practice was reported by the professionals in relation to whether the courts were willing to extend the statutory timeframe for assessment. These issues have been highlighted in the recent case of Re-P-S 32.

Views were divided on the use of care orders to enable prospective special guardians to live with the child whilst being assessed under S24 of the fostering regulations. A care order might be seen as a way of enabling the child to live with the prospective special guardians for that period of assessment with a view to early discharge should the placement be deemed viable long-term. However, children’s services personnel voiced multiple concerns about the difficulties, particularly the costs involved, and the difficulty of bringing the case back to court to discharge the care order and make a special guardianship order.

Professionals suggested:

- Improving the standard of assessment and support to special guardians to achieve paritywith adopters, making better use of pre-proceedings for early identification.

- Special guardians should have more legal advice to help them understand the implications ofthe special guardianship role.

- The forms should be adapted to be written from the perspectives of the child’s needs ratherthan those of parents and prospective special guardians

- Special guardians need more financial, psychological and social support than they currentlyreceive, both during assessment and beyond.

- There should be earlier identification of prospective guardians during pre-proceedings.

Professional views on special guardianship with attached supervision orders

Views were divided on the advantages and drawbacks of attaching a supervision order to a special guardianship order:

- Where the supervision order is used to bolster an untested special guardianship placement, this was felt to be a misuse of the order. However, it was acknowledged that this was one way of assuring at least some additional safeguard for the child where some anxiety about the suitability of the placement persisted.

- In contrast, if the supervision order was being used to help manage contact with birth parents in the context of family conflict, and the local authority provided oversight, some viewed this positively.

The perspectives of the special guardians

Sample: focus groups and interviews with 24 special guardians.

Special guardians were consistently negative about the local authority assessment and the court process:

- They reported that their experience in court was difficult and stressful.

- They felt the court enquiries were intrusive and that they were misrepresented in reports.

- They felt the process lacked transparency – many reported that they did not have party status or were unclear of their party status or the implications of becoming a special guardian.

The extent to which the special guardians were negative however, was influenced by access to legal advice:

- Legal advice facilitated participation in decision-making.

- Where special guardians were unclear of their party status or had insufficient access to legaladvice, they did not feel able to advocate for financial support or other help.

- Negative experiences during assessment and proceedings discouraged special guardians from subsequently seeking help from the local authority.

Given these responses, it is clear that any effort to undertake more in-depth assessment of special guardians needs to be carefully attuned to these strong complaints in its design.

In cases where a supervision order was made alongside the special guardianship order, special guardians felt they were supported with contact, in particular during the first year post-proceedings. In contrast, in some cases without a supervision order, the special guardians described feeling “abandoned” by the local authority post-proceedings, both in terms of a lack of communication to check on their welfare, and insufficient support services offered to deal with arising issues. Special guardians often experienced a range of challenges:

- Housing and financial difficulties were prevalent and caused considerable stress for those affected.

- Children on special guardianship orders can present with difficult emotional and behavioural problems that have to be managed and understood in the context of their past experiences. Without support this can place additional stress on the special guardian.

- Contact with birth parents is an ongoing issue for special guardians and in many cases they felt ill-equipped to deal with this and the impact on the child.

Special guardians recommended that professionals in schools and health services needed a better understanding of special guardianship and the implications for the child.

The perspectives of the birth parents

Based on a sample of five birth parents:

- All the parents felt a sense of relief when a supervision order was made and felt it gave theman opportunity to be “a normal family”. They paid less attention to the terms of the orderthan to the fact that their child was coming home.

- All the parents perceived the supervision order as a form of monitoring, as well as an orderto facilitate help from the local authority.

- All parents were knowledgeable about the care plan and whether their child was on a childin need or a child protection plan. Their experience of the level of support and frequency of social work visiting was variable.

- The parent’s relationship with their child’s social worker emerged as an important factor,influencing the way in which the parent experienced the supervision order as supportive or not. Trust was a critical issue affecting willingness to be open about the need for support.

The parents’ recommendations varied and included the following:

- More help should be made available to single fathers.

- Parents who are being considered for a supervision order should make sure that they are happy with the care plan and if not, should say so.

- It would be helpful for parents to have a full list of the requirements expected of them during the supervision order.

Discussion and conclusions

The contribution of the supervision order to support family reunification

The reforms to the supervision order that were introduced in the Children Act 1989 were intended to stimulate use of this order, as a valuable alternative to a care order that helps to keep families safely together by providing short-term support. This descriptive study provides the first national evidence on their use and outcomes in family justice, and therefore lays down some benchmarks for future studies. Here it is important to remember that supervision orders support permanency only in the short-term.

A first conclusion is that local authorities make very few applications for supervision orders – only 6% of all children are subject to this type of application nationally. Hence applications for supervision orders are exceptional rather than routine when considered in terms of the overall volume of S31 applications issued (between 2007/8 and 2016/17). There has been an increase in the number of standalone supervision orders made at the conclusion of S31 proceedings, but again, when considered as a proportion of all legal orders made at the end of proceedings, we have seen only a 1% increase in the proportion of supervision orders made (from 14% in 2010/11 to 15% in 2016/17) 33. The changing trend is in the use of supervision orders to bolster other family orders – for example, in 2010/17, of all special guardianship orders made, 18% were made in combination with a supervision order, whereas in 2016/17, 30% of all special guardianship orders were made in combination with a supervision order (this is discussed further below).

If 15% of all orders made as a result of S31 proceedings in 2016/17 were for standalone supervision orders to support family reunification, then this legal option needs to be taken seriously and children subject to these orders need to emerge from under the radar. In 2016/17 a sizeable and similar proportion of children were subject to supervision orders at the close of proceedings when compared to special guardianship (17%) and placement orders (16%). However, a critical difference between supervision order children and those subject to special guardianship orders is in the higher return to court rate. 20% of all children subject to a standalone supervision order at the end of care proceedings are estimated to return to court for further S31 proceedings when followed up across the observational window. This risk is higher than for any other family order investigated in this study.

Although this heightened risk means that 80% of children subject to standalone supervision orders did not face this risk of repeat proceedings, it is important that policy and practice becomes more attuned to a concerning 20% of cases where the threshold for significant harm was met again, with 8% of cases estimated to return within 12 months of the previous proceedings.

A further important observation is that there was considerable regional variation in the ratio of supervision orders made vis-a-vis care orders, as an outcome of S31 proceedings. Further investigation of the use of care orders for children returned home is needed, to understand this finding, given that a recent audit completed in the North West 34 has confirmed this particular usage. It is likely that a proportion of children returned home to parents have not been captured by our study. This recent audit also prompts questions about the outcomes of children returned home, subject to supervision orders vis-a-vis care orders.

The intensive case file study in four local authorities helped shed light on protective and risk factors, case complexity, and pathways back to court for children subject to standalone supervision orders. It showed that the majority of children did well during the course of the supervision order but 18% experienced further neglect. However, over the course of the four-year follow-up, an increased proportion was exposed to harm, indicating a deteriorating picture of parenting capacity. These findings are broadly in keeping with other published studies 35.

It is very important to note that both during the course of the supervision order and beyond, housing and financial difficulties created additional stress for parents, which undermined children’s wellbeing. Again, during the follow-up, an increased proportion of families experienced housing and financial difficulties. These are arguably ‘treatable issues’ which, if public services and social welfare provision were better resourced, could readily be addressed.

Given that the longer-term outcomes are concerning for a sizeable proportion of children, this suggests that although the supervision order is protective in the shorter term for many children (i.e. whilst in force), beyond the order, its protective impact diminishes. This raises questions about how vulnerable families can be supported in the longer-term, where they show motivation and capacity for change. This finding is not surprising given that durable recovery from problems of mental health and substance misuse requires a longer period than 12 months. In the absence of intervention to tackle financial and housing problems, it is difficult to know how parents would have fared had these problems been reduced.

Regarding professional decision-making, this study has identified that case complexity, judged by the number and type of parental difficulties and the child’s own problems, was associated with negative outcomes. Specifically, the children of parents burdened by a large number of problems were significantly more likely to experience harm. Specific types of problems such as domestic violence and problems of engagement increased this risk significantly. So too did children’s own difficulties, most notably emotional and behavioural problems and school attendance, absconding and school exclusion. Clearly, there is scope for more nuanced decision-making about risk, attuned to case complexity, and more tightly tailored support with a higher level of visiting, once the supervision order is made.

Isabelle Trowler’s recent report 36 comments on the increase in the number of children subject to supervision applications. However, as stated above, when considered in terms of proportions, the relative use of supervision, both in terms of applications and orders, does not show any marked change in practice, aside from the use of supervision orders to bolster other family orders. In addition, regarding all the cases reviewed in the file study, the threshold was met for S31 proceedings given the level of harm the children were exposed to. It was the court process which appeared to kick-start change for parents, whose problems markedly reduced during the course of proceedings. The likelihood of good progress could not have been predicted in advance from case characteristics alone.

We now also have a better appreciation of family justice stakeholders’ views of supervision orders and their strengths and drawbacks. Views remain as divided today as they were shortly after their introduction in their present form in the Children Act 1989. Helping to keep families together and providing a proportionate alternative to care was put forward by the professionals as their major advantage. But many criticisms were made, in particular professionals felt that supervision orders ‘lacked teeth’. That is, professionals were concerned about managing cases under the child in need (rather than the child protection) framework and that any conditions, should the court choose to impose them (either on the local authority or the parents) were not enforceable. Under a supervision order the local authority does not hold parental responsibility and can arguably only enforce any actions by returning the case to court.

Like the parents, professionals thought that supervision orders in practice, were used to monitor the case as well as offer support, despite the wording of statute which is to ‘advise, assist and befriend’. Tensions and ambiguities in law and practice were manifest in some contradictory opinions among both professionals and parents regarding the value of the supervision order and what needed to change. As noted in the findings, variable patterns of visiting and, no doubt variable experiences of the professional-parent relationship, influenced perspectives. Overall, there was no appetite among professionals to get rid of the supervision order, a finding that also emerged from the very small number of parental interviews, because at the very least, in a context of rationed resources, the supervision order provided some reassurance that some level of ongoing support was possible.

Professionals did not consider that the making of care orders for children at home was a potential way forward, despite the fact that this practice is confirmed in the North West 37. Therefore, based on our quantitative and qualitative evidence on family reunification supported by a supervision order, the key finding is that ways need to be found to strengthen the supervision order rather than to remove this option.

Special guardianship supporting placements with family and friends

The study’s findings on special guardianship lead to several conclusions. At its most basic, they support the overall conclusion of the 2015 DfE Review of Special Guardianship 38 and the leading research 39 that special guardianship is a very valuable option within the menu of legal permanency options to enable children to remain within their family network. The risk of return to court for further S31 proceedings nationally within five years was low (5%), and the case file study showed that all the children had benefited from the change of primary carers in many ways. By the end of the three-year follow-up, very few children were estimated to experience further neglect (6%), exposure to risky parenting as measured by substance misuse (2%) or domestic violence (0%), or a further change in permanent placement (10%) or further S31 proceedings (4%). The placement changes that took place were not the result of neglect but occurred because of conflict with birth parents, children’s own difficulties and ill-health amongst carers.

Against this background of low risk and high sustainability of special guardianship orders nationally, the findings of the case file study on the practice of attaching a supervision order to a special guardianship order are noteworthy. The main factor that influenced the use of a supervision order was geography. 70% of the children in the North had an attached supervision order, but only 30% of those in the South. It suggests that the court and local authority cultures are more important than the perceived riskiness of the placement, a hypothesis that was put forward in the 2015 DfE review of Special Guardianship. In this study, only children’s exposure to parental mental health problems at the start of the proceedings and positive parental engagement during the court process differentiated the two samples. Otherwise, case characteristics did not influence the decision to attach a supervision order and child outcomes were similar in both sub-samples. The results therefore do not suggest any obvious benefits for attaching a supervision order as regards recurrence of neglect, permanent placement change and further S31 proceedings for significant harm. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been worse without it.

The views of the special guardians painted a troubling picture of their experiences of becoming special guardians and their access to support thereafter. Here we need to note that the majority of the special guardians (drawn from a wide range of local authority areas rather than restricted to the four partner local authorities) evidenced strikingly consistent and negative views on assessment and the court process. First, their experiences of the court and the assessments left them feeling isolated, bruised and embattled unless they had access to legal advice. Most did not. They were unclear of their status within the proceedings and often said that they were not a party. All wanted to have meaningful party status from the start of the proceedings so that they could effectively participate in the process. In general, they wanted a voice and thought that special guardians have not been heard or had their needs fully understood. However, when a supervision order was made they found it supportive, especially in relation to managing contact in the first year after the special guardianship order was made. Contact proved to be one of the hardest areas to manage and was associated with further permanent placement change.

Thus, although our national data indicates a low breakdown rate of special guardianship placements, it is clear that more needs to be done to improve the court process for prospective special guardians, such that they are not further burdened by the legacy of a very negative court experience. This is a rights and justice issue, as well as about potentially improving the capacity of special guardians to provide the best care for children. The 26-week statutory timeframe is part of the problem for both professionals and potential special guardians, because this can mean very hurried assessments and a poor experience regarding inclusion for prospective special guardians in the court process and support planning. This latter point is important because they need to fully appreciate both their rights and responsibilities under the special guardianship order in order to make informed decisions about the long-term commitment they are considering undertaking. Timely legal advice is very important for prospective special guardians regardless of whether they are involved at a pre-proceedings stage or join during the course of proceedings.

Regarding professional anxieties, a major issue is the fact that one third of the children (in the case file study) were not living with the special guardians when the final special guardianship order was made, the same proportion to that found by Masson et al in their study of six local authorities in England and Wales 40. Many of these children were still in foster care at the final hearing and moved to their special guardians after the final hearing. This means the special guardianship placement was untested. This stands in sharp contrast to the adoption process, where a final adoption order is only made after the child has lived with adopters for some months on a placement order. This practice is contrary to the original conception of the special guardianship order within the Adoption and Children Act 2002 and associated guidance, which envisaged the order being used for children with strong and established relationships with their new special guardians. In addition, and of equal importance, it is only through the testing of placement that the support needs of the special guardians/placement becomes clear. As stated above, the very latest legislation requires the local authority to demonstrate how any placement will promote developmental recovery.

Options for reform

Supervision orders supporting family reunification

Supervision orders are an important legal option for local authorities and the courts, in cases of child reunification. Without this legal option, hard-pressed local authorities would find it difficult to prioritise this group of children. Thus, the issue is how to strengthen the use of these orders.

Our findings suggest that some improvements could be made without any alteration to the regulatory framework or legislation. The following topics require further debate with stakeholders, to clarify ways forward:

- The value of managing (some) supervision order cases under a child protection framework, to include a more intensive and tailored pattern of visiting. Case complexity would be a key consideration in determining which cases warrant a more intensive approach once children are returned home, or where there remains a number of significant residual difficulties at the close of proceedings.

- The value of extending a supervision order, by way of further application to the courts and the factors that currently discourage this option. One mechanism for stimulating timely consideration of this issue would be to require local authorities through practice guidance or regulations to formally review these cases at eight to nine months, with an element of independent oversight (e.g. Independent Reviewing Officer). Such a review would also surface progress or otherwise in a more formal way, ensuring that cases that ought to return to court for either an extension or new care proceedings do so in a timely manner. The proposed review would ensure that parents were formally warned of this sanction at this time-point.

- The value of additional representation for the child, given the particular vulnerability of children returned home (i.e. they have the greatest risk of breakdown of placement compared to other family orders). In contrast to children in care, children who find permanency at home do not currently have recourse to representation. This might take the form of a volunteer befriending scheme or other initiative.

- Exploration of potential mechanisms that might ensure greater accountability and resource allocation such that obligations within statute on local authorities to ‘advise, assist and befriend’ are better met.

- Better summary of the robust reunification research literature and updating of guidance, recognising the fact that reunification should be a distinct and informed social work activity.

It is also important to note that at present service inputs are not particularly well documented on files, thereby weakening the potential to assess the contribution of the supervision order. We are reluctant to recommend more documentation; however, this point is to note, and to consider whether the development of a standardised way of recording service input would be valuable and feasible. In addition, it is very important to recognise the additional burden that housing and financial difficulties place on families, and the impact this can have for parenting capacity. These issues are entirely treatable but depend on political will. Our study has taken place during an extended period of austerity, and the rise in these types of difficulties is likely to reflect this very tough economic environment. The long-term impacts of poverty on child development and achievement are well established 41.

However some proposals for change are more far-reaching and would merit review of the existing provisions of the supervision order.

There was a broad consensus that an increased use of directions would help strengthen the robustness of supervision orders and potentially enhance parental cooperation with the authorities. However, currently a main deterrent to their use is that breaches can only be used as evidence for further proceedings but are not enforceable by the courts. The key question therefore is whether it would be possible to make directions enforceable, given that the local authority does not hold parental responsibility and the parent’s consent is required to make requirements in relation to their own needs and problems. The advantages are that it would send a message to parents that the role of the supervision order is to monitor as well as to support. Making this function explicit could be advantageous. It would chime better with parents’ understanding of the purpose of the supervision order as an order that monitors as well as supports, and make the dual mandate of this order transparent. But as the law stands, if stronger measures are needed to achieve parental cooperation than the duty to ‘advise, assist and befriend’, a supervision order is not appropriate.

Any changes to the existing framework would need to take account of the risks of extending the role of the state into family life, and weigh it up against the prospects to enhance child safeguarding.

In this regard the study has also raised a question about the value of routine monitoring by the Department for Education of children subject to supervision orders as a separate category within the data collected on children in need. In the absence of an ongoing evidence base, there is a risk that these families may remain under the radar.

Special guardianship orders

Our study builds on existing research, and endorses the positive findings in relation to the benefits of the special guardianship order for the child. The study serves to dispel beliefs that children on special guardianship orders are prone to return to court for further S31 proceedings. In this way it is helping to build a stronger evidence base to inform policy and practice.

At the same time the study shows that there are a number of pressing concerns which require further joint consideration with family justice practitioners and policy makers, to identify options for reform and next steps. Specifically:

- a. How to improve the court experience for prospective guardians whilst ensuring a robust assessment process that is child focused and addresses their long-term needs for permanency. Debate is needed on how to:

- Ensure that special guardians, as a matter of right, acquire party status at the earliestappropriate opportunity to enable their full participation and representation in the proceedings and understanding of the long-term commitment a special guardianship order confers.

- Strengthen the assessment process and issues to be considered in order to promote robust evidence based decision-making regarding the impact on the child and special guardian’s immediate family and wider network. Bring it in line with assessment processes for other permanency options.

- Identify factors that would justify extending cases beyond the 26-week time limit in a way that achieves consistency across the family justice system.

- b. How to address the support needs of special guardians, with particular reference to financial and housing issues, and contact with birth parents and family network in the short and longer term.

- The value of new guidance on contact needs to be considered. Its purpose would be to inform decision-making around contact arrangements, including dealing with situations where contact is problematic. This should be grounded in the available evidence, and take into account the specific features of special guardianship.

- c. Hearing the voice of the special guardian. Finding ways of ensuring that their views are heard clearly in policy and practice formation and reform is a priority.

- As part of this objective, identifying strategies to ensure that special guardians are consulted on the proposals for reform outlined above would help kick-start the process.

Special guardianship orders with attached supervision orders

The study has not provided a clear cut answer regarding the value of attaching a supervision order to a special guardianship order. Questions remain as to the rationale and benefits of the combined order with views and practices differing markedly across the country. However, with 30% of all special guardianship cases resulting in an attached supervision order in 2016/17, it is important to continue to monitor this trend. It is this use of supervision orders which constitutes a change in practice and increased use of supervision orders nationally. Debate is needed on the following issues:

- How to ensure that work to improve the robustness of the assessment of prospective special guardians takes into account the current use of supervision orders in combination with special guardianship orders – with particular reference to the 26-week timescale, contact and support functions.

- As noted above, consideration of alternative ways of intervening to resolve contact disputes, such as brief therapeutic intervention in the family system. Alternative interventions may negate the need for or be better than using a supervision order attached to the special guardianship order.

- The issue of regional variation, which warrants further exploration and awareness-raising as a function of the local Family Justice Boards and the Family Justice Board.

Next steps

A number of options for reform have been set out in the light of the study’s findings. Our next steps are to seek dialogue and host consultation events which bring together family justice stakeholders to debate the options for reform and consider their feasibility in the current context of policy and practice.

Findings from the consultation events will be fed back to relevant bodies – to include the President’s Office, the Adoption and Special Guardianship Leadership Board, the Family Justice Council, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, local authorities, the Association of Directors of Children’s Services, local family justice boards and advocacy and user organisations.

We shall publish a summary of the consultation recommendations through the Centre for Child and Family Justice at Lancaster University.

1 Children Act 1989 (S35)

2 Children Act 1989 (S35 (1)[a]).

3 Based on Cafcass data between 2007/08 and 2016/17. In 2017/18 Cafcass reported a 2.6% drop in the number of applications for a care order

4 Crisis Review: options for change (2018) London: Family Rights Group. https://www.frg.org.uk/images/Care_Crisis/CCR- FINAL.pdf

5 Re B (A Child) [2013] UKSC 33 and Re B-S (Children) [2013] EWCA Civ 1146.

6 Re P-S (Children) [2018] EWCA Civ 1407.

7 Department for Education (2015) Special Guardianship Review: report on findings, December. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/487243/SGR_Final_Co mbined_Report.pdf

8 Children and Families Act 2014 (S.14 (2)).

9 Myers, J (2017) Serious case review ADS14: Polly [full overview report]. Derbyshire: Derbyshire Safeguarding Children Board

10 Hunt, J, McLeod, A. and Thomas, C. (1999) The last resort: Child protection, the courts and the 1989 Children Act. London: Stationery Office.

11 Children and Social Work Act 2017 (S.8).

12 Full details of the methodology can be found in the main report and its technical appendices.

13 Whilst Cafcass has records from 2007/08, the data on legal outcomes is more reliable from 2010/11.

14 It is recognised that this approach could produce errors. For example, ROs/CAOs (live with) could be made to a previously non-resident parent or to a family and friends carer; a care order could be made to a family and friends carer or to parents.

15 Made if the court has applied the principle of non-intervention under section 1(5) of the Children Act 1989. This provides that the court shall not make an order unless it considers that doing so would be better for the child than not making an order at all (A Guide to Court and Administrative Justice Statistics – Glossary). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/297963/guide-to- court-and-administrative-justice-glossary.pdf

16 Kartsonaki, C. (2016) ‘Survival analysis’, Diagnostic Histopathology, 22(7), pp. 263-270. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756231716300639

17 Hodson, D., NSPCC (2015) Neglect appraisal tool. This tool was used instead of relying on the number of children subject to child protection plans due to significant harm by abuse category. Although a potentially valuable proxy, it risked underestimating any abuse or neglect in children in need cases or overestimating the numbers where children remained on a child protection plan at the start of the supervision order.

18 All birth parents and special guardians in the case file studies were eligible to take part in the interviews on a voluntary basis. Letters were sent out by the local authority enclosing a letter from the research team with an invitation to take part. A second letter was sent out if there was no response to the first letter. The strategy was subsequently modified to include parents whose children had recently been placed on a supervision order and a leading charity agreed to post details of the study on its website. The recruitment of the special guardians for the focus groups was carried out with the support of the charity Grandparents Plus. The researchers attended a conference and presented information on the aims of the study and wish to recruit special guardians (with or without a supervision order). Interested special guardians contacted the research team to confirm participation and the focus groups were then set up and coordinated by the charity.

19 15 lawyers, 51 social workers, team leaders and IROs.

20 Pseudo-anonymised means that all personally identifiable information is replaced with artificial identifiers or pseudonyms.

21 We calculated the number of extension of supervision order applications which equated to 0.5% of all S31 applications. However, extension of supervision order applications were otherwise excluded from all analyses.

22 All findings throughout this report are based on the child as the unit of analysis.

23 Cusworth, L., Biehal, N., Whincup, H., Grant, M. and Hennessy, A. (forthcoming), Children looked after away from home aged five and under in Scotland: experiences, pathways and outcomes, University of Stirling.

24 Figures are based on the use of the NSPCC Neglect Appraisal Tool.

25 Calculated out of 10. The problems were: mental health problems; material difficulties (housing or financial); substance misuse (alcohol or drugs); lack of social support network or relationship difficulties; domestic violence; offending; physical disability; physical health problems; learning difficulties.

26 Methods of survival analysis are used to produce these calculations.

27 A child in need is defined under the Children Act 1989 as a child who is unlikely to achieve or maintain a reasonable level

of health or development, or whose health and development is likely to be significantly or further impaired, without the provision of services; or a child who is disabled. A child is made subject to a child protection plan after a S47 enquiry under the Children Act 1989 if the child is considered to be suffering or is likely to suffer significant harm to ensure their safety and promote the child’s health and development. ‘Working Together To Safeguard Children’ (2018), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/729914/Working_Together_to_Safeguard_Children-2018.pdf

28 This is very similar to the rate of emotional and behavioural problems seen amongst a group of children living with kinship carers in Scotland on Section 11 Children (Scotland) Act 1995 or Kinship Care orders, the nearest equivalent to a special guardianship order. See Cusworth, L., Biehal, N., Whincup, H., Grant, M. and Hennessy, A. (forthcoming), Children looked after away from home aged five and under in Scotland: experiences, pathways and outcomes, University of Stirling.

29 0.5% of all applications to the courts were for an extension of the supervision order.

30 RE T A minor, Care or Supervision Order, [1994] FLR103

31 Currently the court cannot specify the directions to be given as a condition of a supervision order (Re V.(Care or Supervision Order) [1996] 1FLR 776)

32 Re P-S (Children) [2018] EWCA Civ 1407

33 The trend we report regarding the overall increase in the number of supervision order applications is similar to that reported in the MoJ data (MoJ Family Court Tables) and used by Isabelle Trowler in her recent report “Care proceeding in England: the case for clear blue water” (2018). However, it is important to consider this trend (rise in number) in the context of an overall increase in S31 proceedings. When we consider the ratio of supervision order applications of all S31 proceedings during the past ten years, there has been little overall change in the ratio.

34 Hodgson, S., Hayes. And Bunker, P. (2017) Placement at home with parents, Sefton MBC, CAFCASS and ADCS.

35 Farmer, E., Sturgess, W., O’Neill, T. and Wijedasa, D. (2011) Achieving Successful Returns from Care. London: BAAF. Wade, J., Biehal, N., Farrelly, N. and Sinclair, I. (2011) Caring for abused and neglected children: Making the right decisions for reunification or long-term care. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Farmer, E, 2018, ‘Reunification from Out-of-Home Care: A Research Overview of Good Practice in Returning Children Home from Care’. University of Bristol.

36 Trowler, I. supported by White, S., Webb, C. and Leigh, J.T. (2018) Care Proceedings in England: the Case for Clear Blue Water. University of Sheffield.

37 Hodgson, S. Hayes, S. and Bunker, P (2017). Placement at home with parents: North West Audit Summary Report, Sefton MBC, CAFCASS and ADCS

38 Department for Education (2015) Special Guardianship Review: report on findings, December. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/487243/SGR_Final_Co mbined_Report.pdf

39 Wade, J., Sinclair, I., Stuttard, L. and Simmonds, J. (2014). Investigating Special Guardianship: experiences, challenges and outcomes. London: Department for Education.

40 Masson, J., Dickens, J., Garside, L., Bader, K., and Young, J. (2018). Reforming care proceedings 1: Court Outcomes. University of East Anglia

41 Cooper, K. and Stewart, K. (2013) Does money affect children’s outcomes? A systematic review, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Cooper, K. and Stewart, K. (2017) Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes? An update CASE paper 203, LSE, ISSN 1460-5023. Bywaters, P., Bunting, L., Davidson, G., Hanratty, J., Mason, W., McCartan, C. and Steils, N., 2016. The relationship between poverty, child abuse and neglect: an evidence review. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, United Kingdom. Schoon, I., Jones, E., Cheng, H. and Maughan, B., 2012. Family hardship, family instability, and cognitive development. J Epidemiol Community Health, 66(8), pp.716-722.

Organisations

-

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research

The Centre for Child and Family Justice Research -

Lancaster University

Lancaster University