Overview

This report explores the prevalence, circumstances and experiences of parents with learning disabilities or difficulties involved in care proceedings concerning their babies. It sets out key findings from an examination of court bundles, children’s social care records and interviews with parents, lawyers and social care professionals in England.

Executive summary

This mixed method study, completed by the Institute of Public Care at Oxford Brookes University in September 2023, explored three important questions about parents with learning disabilities and learning difficulties in relation to care proceedings involving their babies.

- What proportion of care proceedings cases regarding babies (children under 12 months old) involve parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties?

- What are the broader characteristics and circumstances of these parents?

- What are their experiences from the point of referral to children’s social care services through to the conclusion of care proceedings?

The study findings indicated the likely high prevalence of learning disabilities or difficulties among parents involved in care proceedings regarding babies. It underscores the importance of implementing both the Working Together with Parents Network (WTPN) 2021 Update of the 2016 Good Practice Guidance on Working with Parents with a Learning Disability (WTPN 2021) and the Best Practice Guidelines for When the State Intervenes at Birth (Mason et al. 2023) across public services in England.

About the data

The data in this study relates to England. It came from:

- court bundles and social work records relating to the 50 most recently concluded care proceedings (at March to April 2023) concerning a baby aged under 1 year at issue in four different local authority areas (200 cases in total)

- interviews with four mothers with learning disabilities or difficulties who had experience of care proceedings

- interviews with 42 social care professionals and 17 legal professionals.

Definitions

The study’s starting point for defining and identifying parental learning disabilities was the definition endorsed by the Department of Health and Social Care, 2001 (as cited in Public Health England 2023):

A significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills, with a reduced ability to cope independently, which started before adulthood.

The study’s starting point for defining and identifying parental learning difficulties was the definition endorsed by Public Health England (2023):

A reduced intellectual ability for a specific form of learning and includes conditions such as dyslexia (reading), dyspraxia (affecting physical coordination) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

When it comes to parents involved in children’s social care or care proceedings, definitions of learning disabilities and learning difficulties can have limitations as they tend to be deficit-based and do not specifically relate to parenting. In this study we found that, where parental learning disabilities or difficulties were suspected in general terms prior to court proceedings, a cognitive assessment undertaken during proceedings (invariably including an IQ testing element) often provided much more focus and depth of understanding.

The study also recognised learning difficulties as an umbrella term for a spectrum of learning disabilities and learning difficulties, including as defined above, and to recognise people with moderate intellectual disabilities, ‘who do not have a formal [learning disability] diagnosis but struggle with similar issues’ (Tarleton and Turney 2019).

Key Findings

What proportion of care proceedings cases regarding babies involve parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties?

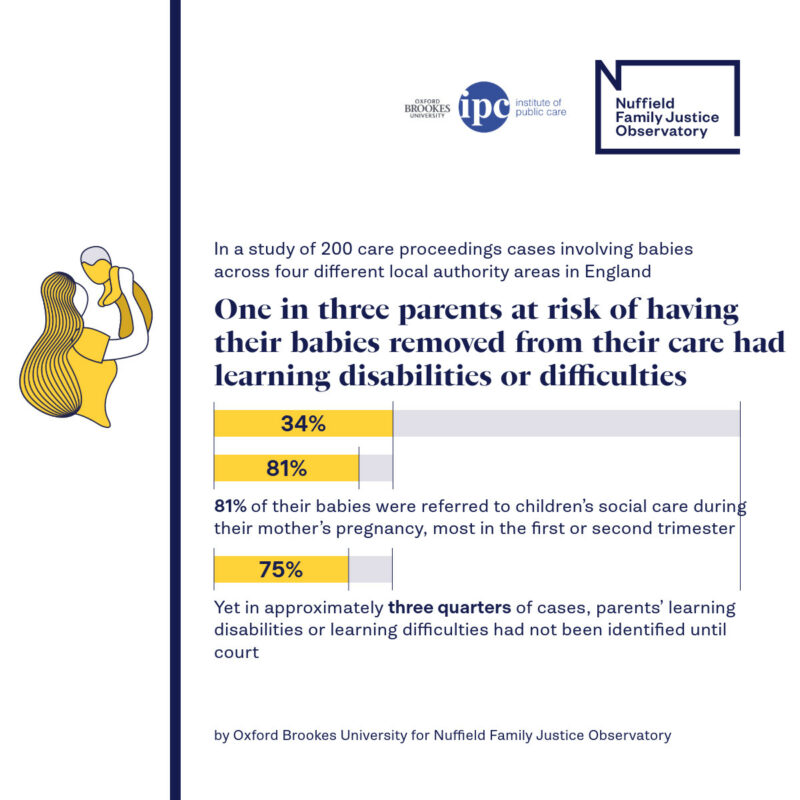

- In one third (34%) of the 200 most recently concluded care proceedings cases examined for the study, there was reliable – mostly expert – evidence that one or more of the parents involved had learning disabilities or learning difficulties. The expert evidence was documented within a psychologist’s (psychological or cognitive) assessment undertaken during care proceedings in 75% of cases.

- This prevalence varied by local authority area (e.g. 44% in a county area and 22% in a London borough). While these differences have implications for the generalisability of the study’s prevalence findings, they do accord with other Public Health England (2016) evidence also demonstrating varying prevalence rates of adults with learning disabilities within the whole population across different parts of England.

- Mothers in the case file sample had learning disabilities or learning difficulties in just under one third (30%) of all recently concluded care proceedings regarding babies. In a smaller proportion of cases, fathers (13%) or both parents (9%) had learning disabilities or learning difficulties.

What are the broader characteristics and circumstances of these parents?

- A high proportion (81%) of the children were referred to children’s social care during their mother’s pregnancy. Most of these pre-birth referrals were made in the first and second trimester of the pregnancy. Only a small proportion (10%) were made very close to the time of the birth (i.e. within the final few months of the pregnancy).

- While approximately one quarter of the mothers and fathers in the study were under 21 years old at referral, mothers were 26 years old on average and fathers were 28 years old on average.

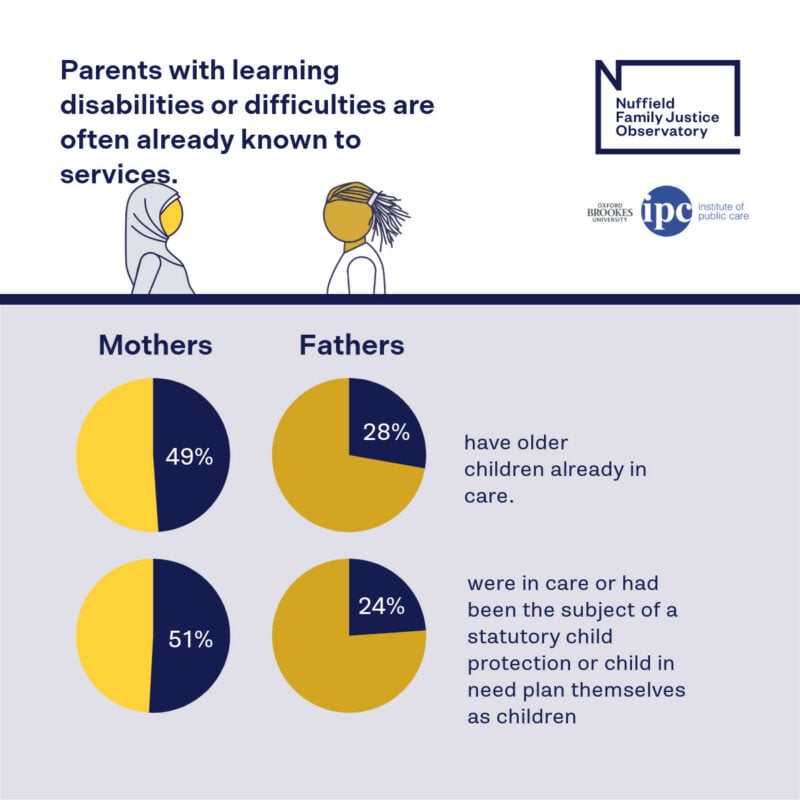

- Just over half (51%) of the mothers and just under a quarter (24%) of the fathers were known to have been in care or subject of a statutory child protection or child in need plan as children.

- Nearly half (49%) of the mothers and 28% of the fathers were known to have older children already taken into care.

- Combined data from case file analysis and the professional interviews suggested there were usually other areas of professional concern when the babies became subject of care proceedings, in particular: parental mental health, parental substance misuse, domestic abuse, or parental vulnerability to exploitation in the community. Some professionals thought these other factors made it harder to identify or focus on parental learning disabilities or difficulties – because they posed a more obvious immediate risk to children.

What are their experiences from the point of referral through to the conclusion of care proceedings?

Timeliness and the significance of delay(s)

- In approximately three quarters of the reviewed children’s case files, parents’ learning disabilities or learning difficulties had been identified at a very late stage – that is, within care proceedings. This included identification within the current care proceedings in approximately 45% of cases and within previous care proceedings regarding an older child in approximately 30% cases (i.e. where there were recurrent proceedings). Professionals of all types thought this was far too late and that there were missed opportunities to identify at an earlier stage.

- The main barriers to earlier identification described by professionals of all types included: the costs for local authorities in getting an assessment done earlier and social workers not having the right training, experience, authority, or time to screen effectively or to trigger a further in-depth assessment.

- Late identification of parental learning disabilities or learning difficulties meant that social worker communications, key (parenting) assessments and parenting support services were very unlikely to be tailored to parents’ learning needs. Professionals of all types considered that, in these circumstances, parents were less likely to be engaged effectively in pre-proceedings work and resources would be wasted. For example, in-depth assessments that had not been tailored would need to be repeated in care proceedings. Care proceedings might also be delayed – the case file analysis identified that an average length of proceedings for parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties was 39 weeks and, in 76% of cases, the proceedings needed to be extended beyond 26 weeks.

- Late identification of parental learning disabilities or difficulties also meant that important decision-making processes, such as child protection case conferences, formal pre-proceedings meetings and initial care proceedings hearings were not tailored, with a strong risk then that parents did not fully understand what was happening or the implications.

- The case file analysis also identified a high proportion (65%) of cases involving parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties that were commenced at either no (same day) notice or with less than 3 days’ notice. Shortened notice would mean that there was little time for a parent to instruct a solicitor or for a guardian to make enquiries and advise the court.

- Although many of the parents referred to children’s social care pre-birth had in theory between 7 and 4 months before the birth to undertake purposeful work with the support of social care services, the commencement of this support was frequently delayed until around the time of the child’s birth, at which point ‘the clock was ticking’ in terms of parents being able to prove in a timely way – that is, before proceedings started or were completed – that they could provide good enough parenting.

Adequacy of support for parental engagement and participation

- Social worker communications were described by interviewees as a vital aspect of parental engagement and participation. The case file analysis and interviews unearthed some examples of good quality communication, tailored to parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties. However, evidence suggested that this key aspect of social work practice was very variable in terms of quality. Professional interviewees suggested that the main reasons for this included a lack of adequate training and insufficient time to put theory into practice.

- Family group conferences or family network meetings were regularly used (including in 52% of the case files involving parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties) and were considered by all interviewee types to have an important role in encouraging broader family member support at a time when parents often felt particularly alone, scared or vulnerable. However, the study found very little evidence that these meetings took account of parental learning disabilities or difficulties. In many cases these disabilities or difficulties had yet to be identified, and therefore extended family members could not be helped to understand their involvement or role.

- Lay advocates were inconsistently (across different local areas) and overall infrequently available to support parents with learning disabilities to engage and participate in pre-proceedings, and interviews with professionals suggested these advocates often did not have the right training to do so.

- At the conclusion of care proceedings, particularly where children were removed from their parents’ care, interviewees of all types suggested that support for parents frequently diminished drastically and that parents experienced ‘radio silence’. The main or only mechanism for connecting parents with important ongoing support (such as advocacy, adoption counselling, adult social care, or specialist services geared towards preventing repeat removals) was the child’s social worker. This mechanism was considered innately flawed, as parents might not wish to engage with the child’s social worker at the end of care proceedings. Lay advocates were often considered better placed to help parents access support at this point.

Sufficiency of reasonable adjustments

All public bodies, including local authorities and courts, are required to make reasonable adjustments to ensure that people with disabilities are not put at a substantial disadvantage (Section 20 of the Equality Act 2010).

- Our study found that parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties frequently had to engage with multiple assessments or assessors and found this stressful. Some parents thought assessors had already made up their minds or were overly critical.

- An important determinant of care proceedings’ outcomes was parenting capacity. Standardised assessment tools were often applied, such as parent assessment manual (PAMS) or ParentAssess. An important limitation of the more frequently used tool, PAMS, included that it was not used in practice as it had been intended – this is, to assess, tailor learning, and reassess, rather than as a standalone assessment. This meant that parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties had a limited chance to prove themselves with the support of targeted learning. The more recently developed ParentAssess tool was favoured by many professional interviewees with experience of it, including because it could be adjusted to incorporate all the issues in the case and was also cheaper for local authorities to implement.

- Actual support for parenting was very inconsistently or insufficiently adjusted for parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties – this is, in only approximately one third of the case files examined. This absence of reasonable adjustments, combined with a lack focus on the right topics, was particularly noticeable in cases involving pre-birth work with parents.

- It was difficult to access adult social care expertise or support for parents under the Care Act 2014. Within the case file sample involving parents with learning disabilities or learning difficulties, this support was requested in just over a quarter of cases (27%) and provided in 15% of cases. Some professionals considered that social workers were put off even requesting this kind of support because they knew that the eligibility thresholds for it were so high.

- Within formal pre-proceedings, there was very limited evidence of reasonable adjustments. However, there was much more evidence they were being made within actual care proceedings – including upon advice from an expert psychologist (cognitive assessment) or court intermediary. However, these adjustments were usually only made in care proceedings after a cognitive assessment and/or court intermediary assessment had been undertaken, which meant they often only really helped parents at a final hearing stage. Parents and professionals also thought that jargon was still too frequently used in care proceedings and, without a lay advocate, parents might not understand what was happening. Legal professionals often considered that the consistency of good practice would be improved by requiring family court judges and advocates to have more specific training in this area.

Key recommendations

The key finding with regards prevalence (at around one third of cases) lends significant weight to the need to strengthen practice within local authorities, legal services and courts.

Local authorities

- Require children’s social workers to screen for and, where indicated, to organise a more in-depth assessment of a parent’s learning needs as a core part of any early assessment work, including at a pre-birth stage and at the latest during formal pre-proceedings.

- Make arrangements for social workers and family support workers to engage in regular, mandatory post-qualification training to identify, communicate effectively with and tailor support for parents with learning disabilities or difficulties.

- Incorporate and nurture learning disabilities expertise within child and family social work teams undertaking child in need and child protection work.

- As outlined in Best Practice Guidelines for When the State Intervenes at Birth (Mason et al. 2023), end the practice of delaying support until after a pre-birth assessment has been completed, or until the child’s birth, and emphasise the importance of starting to engage and work with parents as soon as possible.

- Improve the commissioning and availability of lay advocacy so that it is more consistently available pre-proceedings and provided by people sufficiently trained in working with parents with learning disabilities or difficulties.

Senior leaders of the judiciary, bar and solicitors

- Improve the rollout of vulnerable witness training for all advocates working in care proceedings.

- Develop specific training for the judiciary on directing proceedings involving parents with learning disabilities.

- With national partners, consider whether and how some or all Family Drug and Alcohol Court (FDAC) processes could be applied to parents with learning disabilities or difficulties to improve the experience and effectiveness of support offered during and at the conclusion of care proceedings.

National policy support for improvements

- Improve the visibility and impact of the Good Practice Guidance on Working with Parents with a Learning Disability (WTPN 2021) and the Best Practice Guidelines for When the State Intervenes at Birth (Mason et al. 2023), including within the refreshed Working Together to Safeguard Children (HM Government 2023) and other key national guidance.

- Encourage more timely identification of parental learning disabilities or learning difficulties during pre-proceedings rather than in court – on the basis that earlier identification leads to better assessments and supports for parenting as well as reduced delay for the child. Develop new, or road test existing, approaches to timely (pre-proceedings) screening for and identification of parental learning disabilities or learning difficulties by social care services, including tools, pathways and protocols.

- Explore with Social Work England the extent to which social work qualification training includes a sufficient focus on the skills and knowledge base required to work effectively with parents with learning disabilities or difficulties.

- Provide funding and other incentives to the sector to pilot specific improvements for parents with learning disabilities and difficulties such as: tailoring pre- and post-birth support and services; embedding learning disability specialists within children’s social care teams; and developing mechanisms to ensure parents are more consistently directed to tailored post-proceedings support.

What do we mean by learning disabilities and learning difficulties?

The study’s starting point for defining and identifying parental learning disabilities was the definition endorsed by the Department of Health and Social Care (2001), frequently used in the context of adult health and social care services:

A significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills, with a reduced ability to cope independently, which started before adulthood (as cited in Public Health England 2023).

The study’s starting point for defining and identifying parental learning difficulties was the definition endorsed by Public Health England (2023):

A reduced intellectual ability for a specific form of learning and includes conditions such as dyslexia (reading), dyspraxia (affecting physical coordination) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The study also recognised and sought evidence in relation to other frequently applied definitions and references, including the following.

- Increasing international reference to ‘intellectual disability’ rather than ‘learning disability’ (Cluley 2018), including – but not exclusively – for clinical definitions and diagnostic criteria applied by psychologists in the UK, as set out in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) (World Health Organization 2022) and the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). In practice, UK-based psychologists are regularly called upon to determine whether an adult has a learning or intellectual disability including with reference to IQ testing undertaken within a broader clinical assessment (wherein an overall IQ score of less than 70 is considered an indicator – not a predictor – of intellectual disability) (The British Psychological Society 2015).

- ‘Learning difficulties’ as an umbrella term for a spectrum of learning disabilities and learning difficulties, including as defined above, or to recognise people with moderate intellectual disabilities, ‘who do not have a formal [learning disability] diagnosis but struggle with similar issues’ (Tarleton and Turney 2019).

Identifying parents with learning difficulties and disabilities in practice

When it comes to parents involved in children’s social care or care proceedings, definitions of learning disabilities and learning difficulties can have limitations as they tend to be deficit-based and do not specifically relate to parenting. In this study we found that, where parental learning disabilities or difficulties were suspected in general terms prior to court proceedings, a cognitive assessment undertaken during proceedings often provided much more focus and depth of understanding.

These psychological or cognitive assessments invariably included an IQ testing element, [1] as is considered ‘an essential component of the overall assessment’ (The British Psychological Society 2011; 2015). Overall IQ scores and scores by cognitive ‘domains’, combined with other information from court documents or from parents themselves, enabled psychologists undertaking the assessments to explore parents’ relative learning strengths and difficulties.

10 aspects of parental learning disability or learning difficulty: ‘cognitive functioning’

In summary or concluding paragraphs within cognitive assessments, the following 10 aspects were frequently explored and with relevance to the parenting task:

- Understanding and comprehension, particularly understanding abstract concepts (such as time) or complex instructions.

- Processing and speed of processing information, including oral and written communications.

- Reading or writing (literacy).

- Attention and concentration.

- Retention of information (memory).

- Reasoning (verbal or non-verbal).

- Independent living skills (managing finances, problem solving or forward planning).

- Adaptability, including to new situations or to develop new skills.

- Social interactions.

- Understanding other people’s thought processes or needs.

- Using assessment measures recommended by The British Psychological Society (2015), such as Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth UK Edition (WAIS-IV UK) (Weschler 2010).